The Boreas and Orithyia Tapestry Viewed Through the Prism of a Textile Conservator

Fig. 1. René Antoine Houasse (French, 1645–1710). Boreas and Orithyia from a set of scenes from Ovid's Metamorphoses, designed ca. 1690, woven before 1730. Wool, silk, metal thread (19–22 warps per inch, 7–9 per cm.); H. 140 x W. 179 inches (355.6 x 454.7 cm), as measured by Textile Conservation in 1984. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Francis L. Kellogg, 1977 (1977.435)

«It is common practice to rotate items on view from a museum's permanent collection, and this is especially true of tapestries, which are delicate by nature (sensitive to light and pollutant), and therefore can be displayed only for limited periods of time. Such is the case with the tapestry featuring Boreas and Orithyia (fig. 1), which is on display for the first time in more than 10 years in The Florence Gould Gallery, a recreation of a late seventeenth-century interior. It is a masterpiece of craftsmanship and well worth a visit.»

The Boreas and Orithyia tapestry was woven by the Beauvais manufactory in France sometime before 1730, and is part of a set of scenes from Book VII of Ovid's Metamorphoses. In Greek mythology, Boreas, God of the north wind, falls in love with Orithyia, the daughter of Athenian King Erechtheus. The tapestry, which was designed by René Antoine Houasse circa 1690, depicts the scene in which Boreas kidnaps the beautiful princess.

The Metamorphoses tapestries are an important and impressive product of the Beauvais manufactory. There are two sets, one woven with small figures, the other with larger ones. This was not unusual at Beauvais, as the large figures required a higher quality of design and more skillful weavers, and were thus extremely costly to produce and priced accordingly (almost three times higher than the same tapestries with smaller figures).[1] Our tapestry belongs to the set with large figures.

When I was initially tasked with preparing the tapestry for installation, I immediately appreciated its provenance and workmanship. In the weeks that followed, however, as I worked more closely with the tapestry and had numerous opportunities to examine the extraordinarily beautiful details created by the weavers' hands, I uncovered the many subtle displays of expert craftsmanship that makes this work so special, and came to appreciate it as a significant work of art.

It is truer of tapestries than of most art forms that their brilliant intricacies can be appreciated only when viewed up close. From a distance, we see the overall composition; with a closer view, we detect more details; and finally, at very close range, we can truly appreciate the tapestry's breathtaking details and mastery of execution. The Boreas and Orithyia tapestry has a rich palette, with almost every color nuance, and the application of hatching and "blending wefts," or using two or more colors in one yarn, increases the palette and texture in the pictorial effect. The colors are well preserved; reverse and obverse look almost the same.

The Boreas and Orithyia tapestry was cut and resized at least twice. First its size was reduced from the sides; the unequal side edges reveal that the tapestry was torn rather than cut. In a second adjustment, the tapestry's dimensions were increased on both sides by the addition of newly woven material. With the addition of the new piece on each side, the composition of the tapestry's design became much better balanced. The colors of the new areas match those of the original and blend well with the entire panel (fig. 2).

Fig. 2. A portion of the original tapestry next to a restored portion on the right. Photo by the author

Only a trained eye can distinguish restoration from original weaving, but upon close examination it is apparent that the changes to the Boreas and Orithyia tapestry were made by less skillful hands. The specific techniques and small details that made the original weaving so special are not present. The restoration was done professionally, but, as is usually the case, it is not equal to the original high level of craftsmanship.

The Boreas and Orithyia tapestry is very tightly woven and has a high number of warps per centimeter (8–8.5), indicating its excellent quality (more warps allow more creative detail and complicated designs). Another characteristic that makes the weaving special is the use of the "stepping" technique. These small openings, similar to tiny slits, create an unusual, lacy-looking texture. The weavers used numerous stepping techniques to create leaves, folds of cloth, contours, and transitions between colors, and simply to diversify large areas woven either in a single color or in similar colors (fig. 3). The "stepping" texture not only enriches the surface but also brings lightness to the heavy fabric. This technique was not used in the restored parts, which in consequence appear flat and heavier, although the design and colors are similar to the original.

Fig. 3. Details of the tapestry that exhibit a "stepping" technique (small openings). Photos by the author

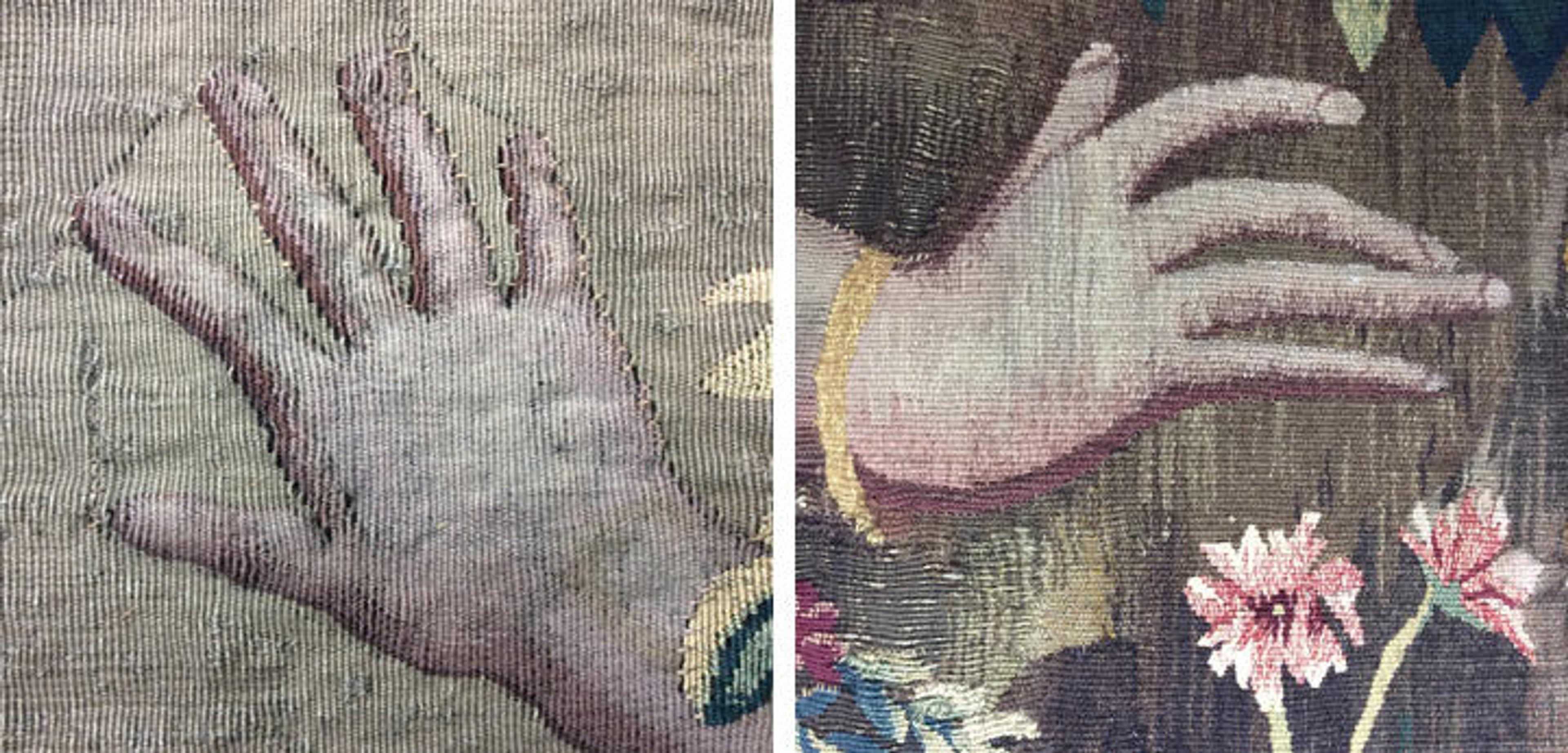

The portrayal of the hands in this magnificent work is particularly noteworthy (fig. 4). In this interpretation of the scene, the weavers used every possible "weaving language." When focusing on the small area of the hand, the artist did not want any interaction with other design parts, and therefore produced "lazy" lines around the hand to separate it from its surroundings. A hand belonging to the woman's figure on the right had been cut off at the first size reduction, but it reappeared following the second restoration, newly woven. The extraordinarily superior weaving quality of the original hand is especially obvious when compared with the newer woven hand of the woman's figure on the right (fig. 5), which is simply a bland copy of the scene.

Left: Fig. 4. Detail of the central figure's original woven hand. Right: Fig. 5. The reconstructed hand of the woman's figure on the right side of the tapestry. Photos by the author

The intense use of "lazy" lines in the original weaving may indicate a division of labor among the weavers: highly skilled artists specialized in weaving faces and hands, others specialized in landscapes, and less experienced weavers worked on backgrounds. Another curious detail is that the tapestry's bottom border is 1.5 cm shorter than its top border. This may have served a specific purpose. When a tapestry hangs on a wall, the top border seems shorter than the bottom border. A difference in the dimensions of the borders equalizes them optically.

The Boreas and Orithyia tapestry is one of the Gould Gallery's exquisite adornments. I strongly recommend visiting the gallery to view this magnificent tapestry created by artists, designers, and weavers 300 years ago.

Notes

[1] Jestaz, Bertrand. "The Beauvais Manufactory in 1690." In Acts of the Tapestry Symposium, November, 1976, 195. San Francisco: Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, 1979.

Olha Yarema-Wynar

Olha Yarema-Wynar is an associate conservator in Textile Conservation.