Showing Signs: Hieroglyphs and Palettes in the Stela of Irtisen

«There is something truly exciting about deciphering an ancient handwriting. Recognizing repeating patterns, erasures, and corrections are often as close as modern scholars can get to a sense of the person who once picked up a pen and wrote the text. The quest to uncover such mysteries by looking at hieratic—the cursive script of ancient Egypt, written with pen and ink—often brings up the question of whether a text was penned by one or more people.»

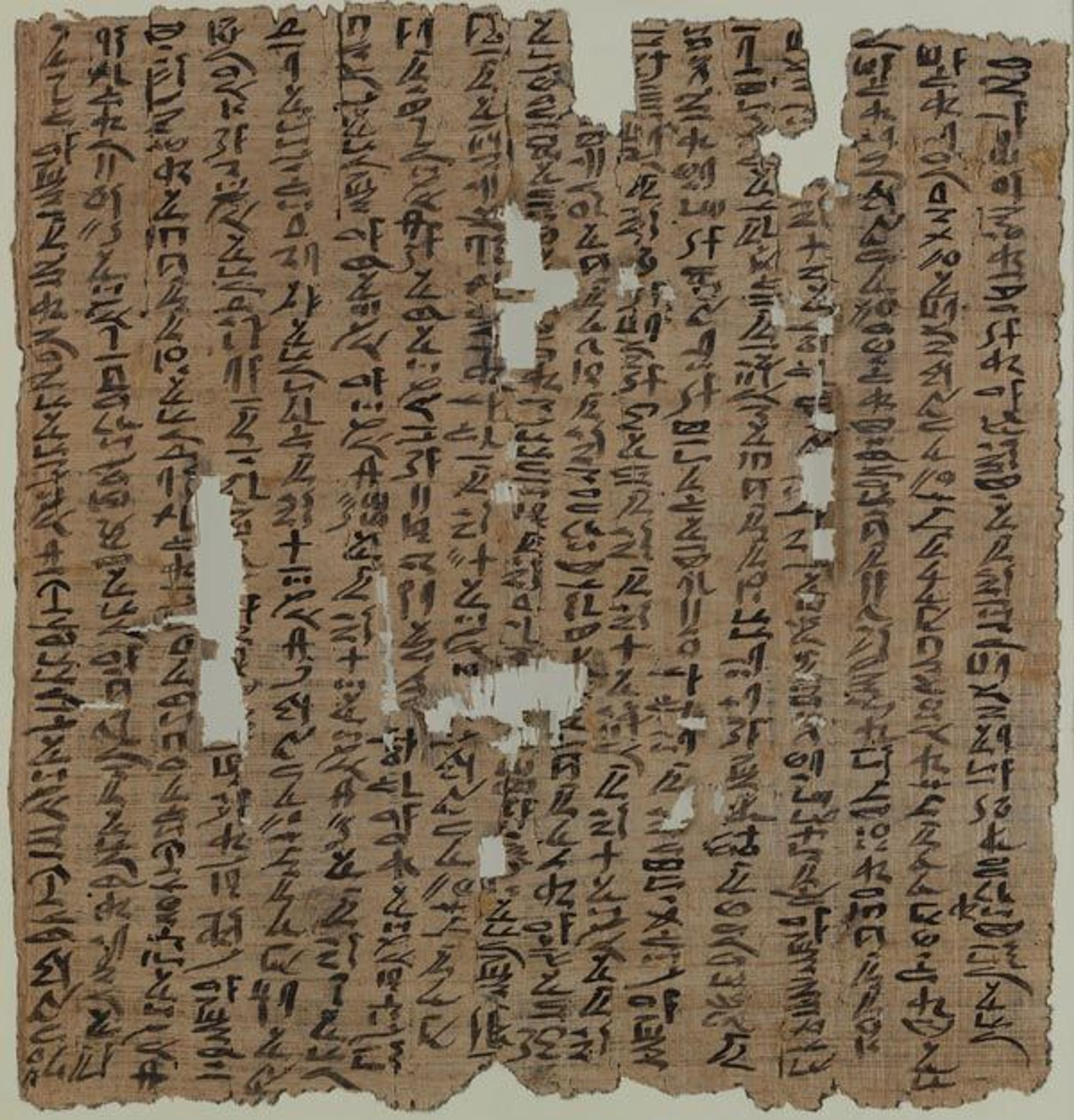

It is possible to identify, for example, three different hands writing the Heqanakht papyri, a group of documents found together in a tomb in Thebes. The one presented in Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom may have been written—as the flow of the ink indicates—by Heqanakht himself (below). In contrast, the production of hieroglyphs—the ancient Egyptian monumental script— often involve more than just a scribe, but additionally a draftsman and an artisan to carve the images into the stone. The multiple hands taking part in the process thereby present a more complex case to interpret.

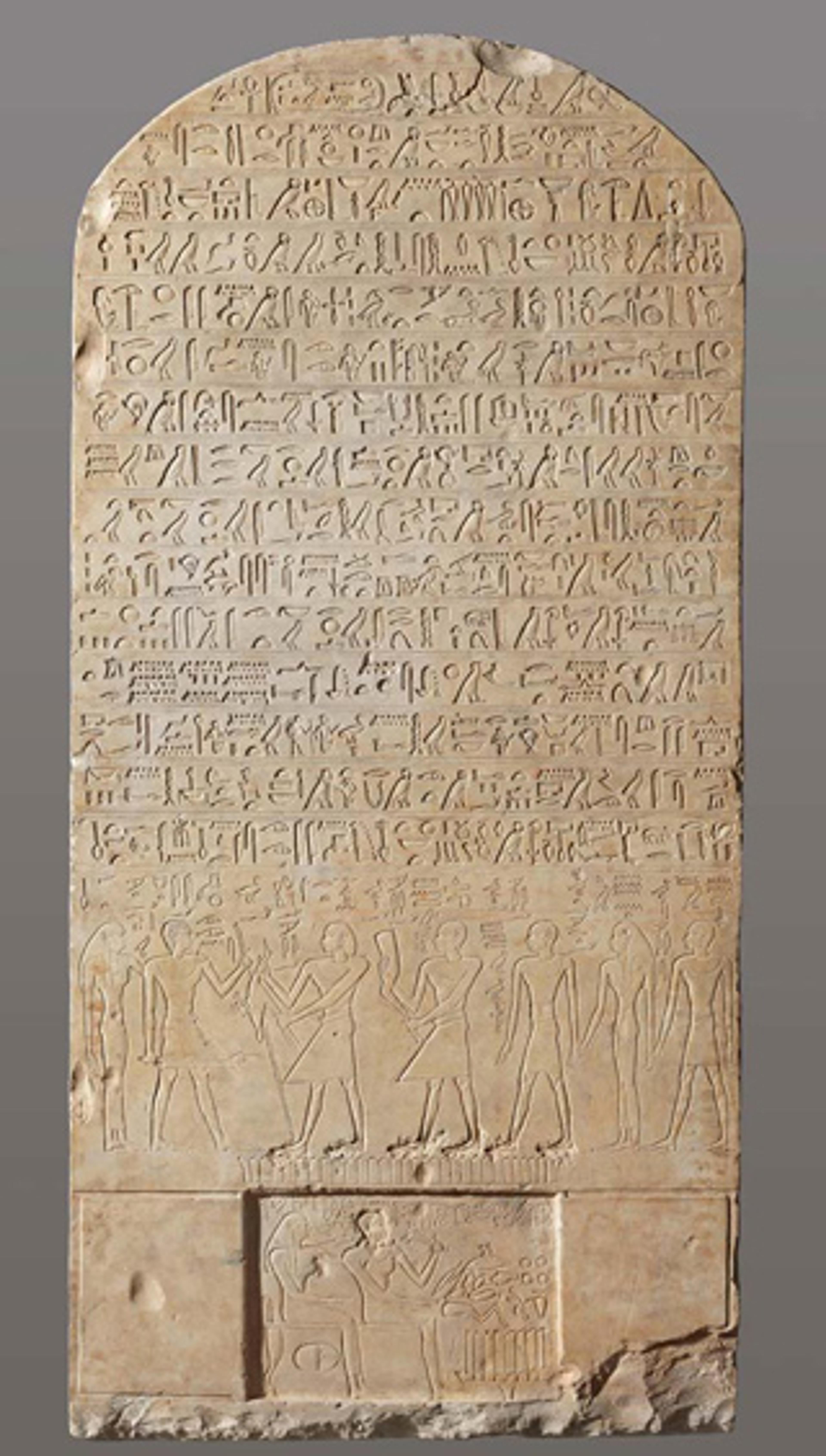

Left: Stela of the Overseer of Artisans Irtisen. Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11, reign of Mentuhotep II (ca. 2030–2000 B.C.). Limestone; 46 1/4 x 22 1/16 in. (117.5 x 56 cm). Paris, Louvre Museum, Departement des Antiquités égyptiennes

Heqanakht Letter I. Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Senwosret I (ca. 1961–1917 B.C.). Papyrus, ink; H. 28.4 cm (11 3/16 in.), W. 27.1 cm (10 11/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1922 (22.3.516)

Nevertheless, in rare instances, we may still get some sense of the person behind them. The stela of Irtisen, which the Louvre has loaned to the Met for display in the exhibition, presents us with such an opportunity. The large limestone monument commemorates Irtisen, who served as Overseer of Artisans late in the reign of Nebhepetre Mentuhotep II. The stela features images of Irtisen as well as his autobiographical text, in which Irtisen speaks of his extensive artistic skill and knowledge.

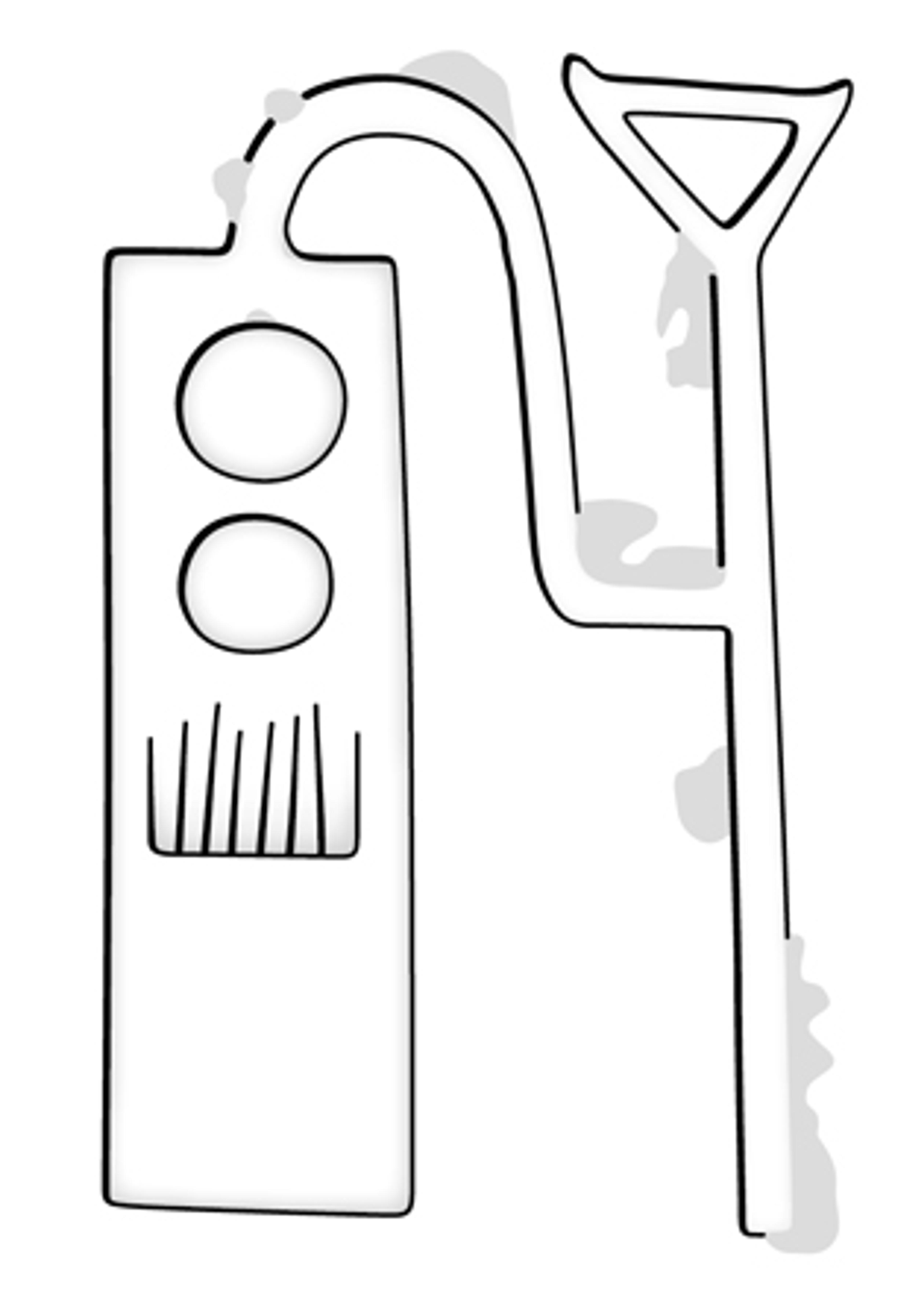

Of particular note is a curious sign that appears in the sixth line of the text, which resembles the hieroglyph shown at left. Albeit immediately recognizable, Irtisen's rendering of the sign for "scribe" slightly differs from the common rendering of the hieroglyph as it appears, for example, in the tomb chapel of Raemkai (below). With this subtle yet significant change, we might sense some of Irtisen's skill in rendering shapes and forms as well as his playful use of them.

Left: Line drawing of the "scribe" hieroglyph as seen on the stela

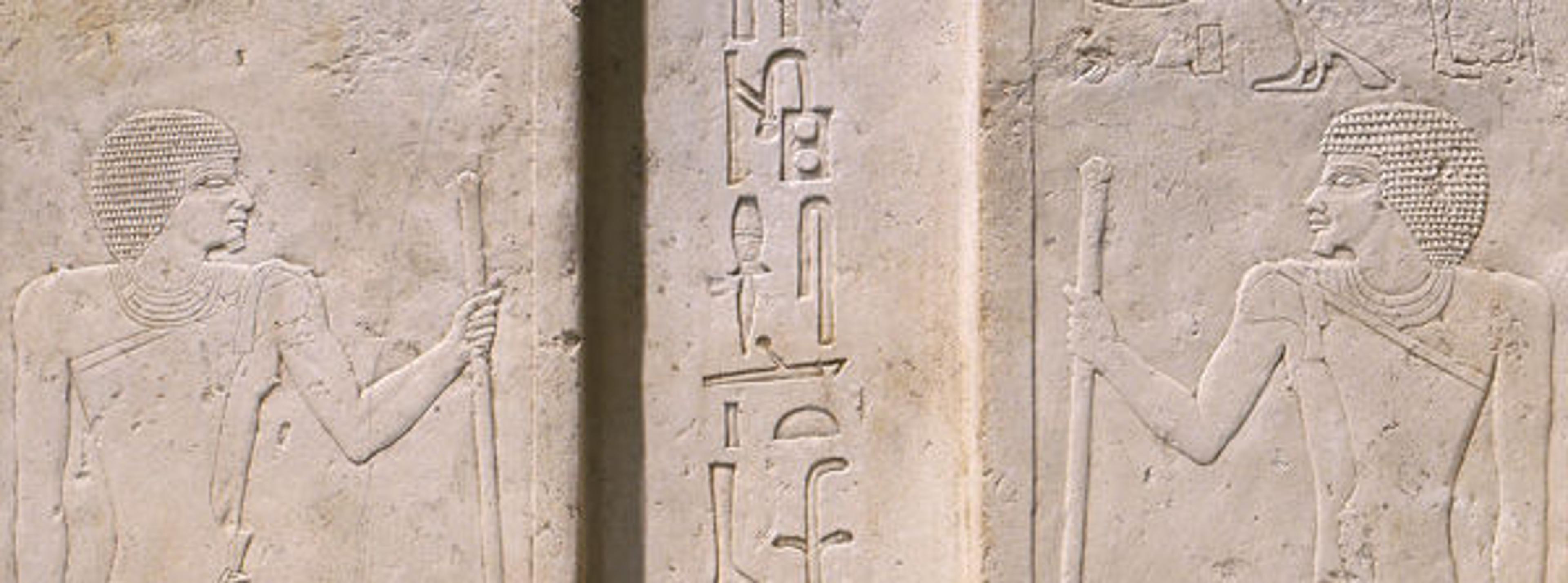

The "scribe" hieroglyph in its most common form resembles the scribal kit as it appears in depictions from the Old Kingdom. The kit in those times was composed of a long pen holder, a bag holding ink cakes, and a palette with two depressions that served as ink wells. This design was introduced into the script early on in the Old Kingdom, and the hieroglyph retained its form even after scribes started employing a new scribal palette.

Tomb Chapel of Raemkai: False Door on West Wall (detail). Old Kingdom, Dynasty 5 (ca. 2446–2389 B.C.). Limestone, paint. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1908 (08.201.1e)

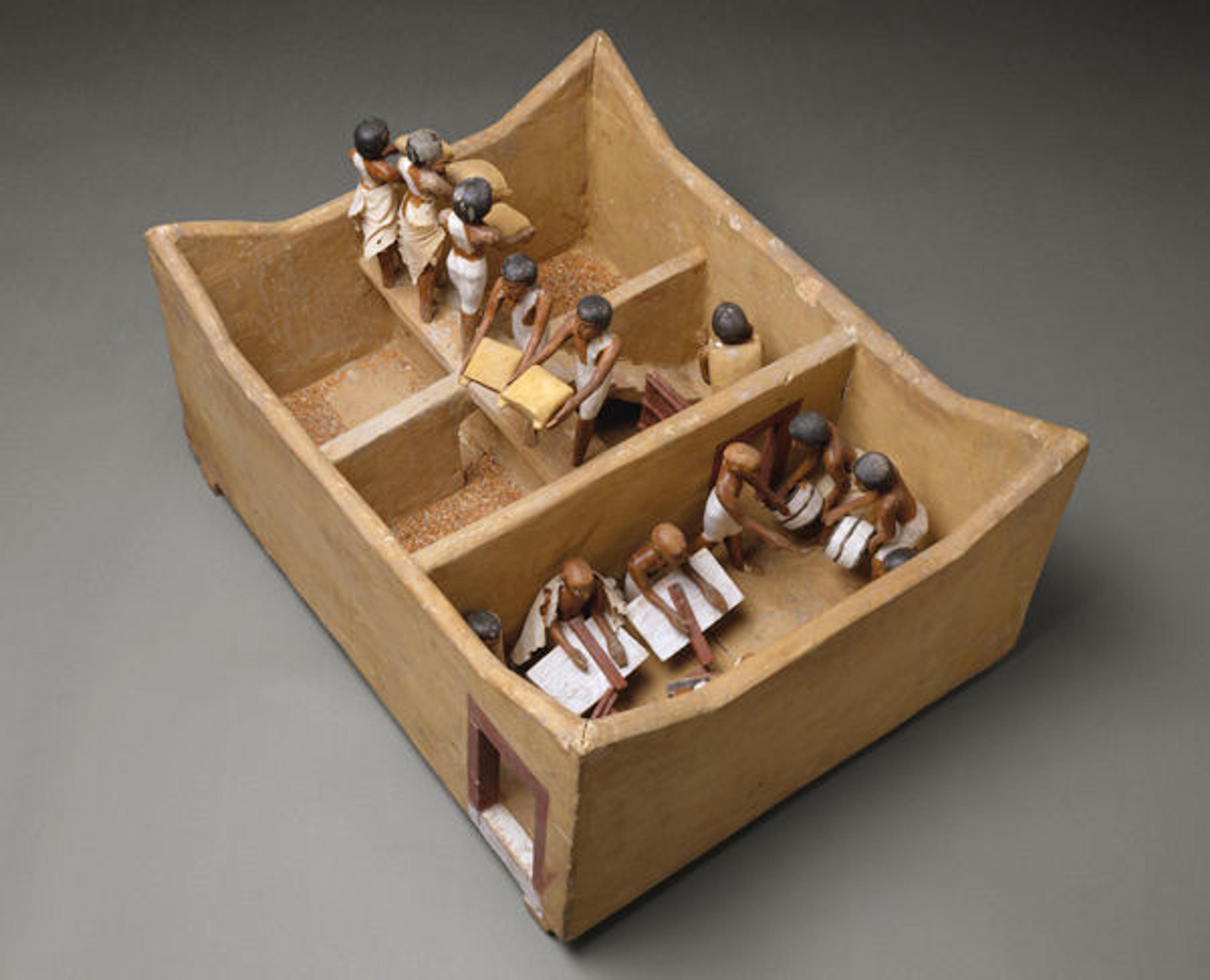

The new palette already appears in late Old Kingdom text, and is visible in a number of places in both the exhibition and the permanent galleries of the Department of Egyptian Art. In a granary model on view, the toiling scribes absorbed in their accounts hold elongated palettes that have two ink wells and another depression in which to hold reed pens. The model realistically paints the upper ink well in black and the lower in red—the two main colors used in an inscription of cursive script.

Model of a Granary with Scribes. Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, early reign of Amenemhat I (ca. 1981–1975 B.C.). Wood, plaster, paint, linen, grain; L. 74.9 (29 1/2 in.), W. 56 cm (22 1/16 in.), H. 36.5 (14 3/8 in.), average height of figures: 20 cm (7 7/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1920 (20.3.11)

A few of these palettes survived from ancient Egypt, one of which is in the Met's collection. The palette still has substantial remnants of the black ink, but the red is almost gone. Finally, a similar palette appears, in two dimensions, in the hands of scribe depicted in one of our facsimiles, which shows a scribe writing while seated on the ground. The hieroglyph to his right communicates the word "scribe," with the hieroglyph retaining its older form.

Scribe's Palette. Middle Kingdom–Second Intermediate Period, Dynasty 12–17 (ca. 2030–1550 B.C.). Wood, pigment; L. 34.6 cm (13 5/8 in.), W. 4.3 cm (1 11/16 in.), H. 1.7 cm (11/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1910 (10.176.62)

Irtisen employs in his stela a composite image that conflates the old with the current. The sign still shows the reed-pen holder on the right, but the palettes depict thin lines that extend out of the depression, imitating the brushes held in such palettes. His choice may very well be intentional since, according to the inscription, Irtisen was the head of an artist's workshop and a draftsman.

Providing viewers with a rare glimpse into the notion of art in ancient Egypt, Irtisen speaks in his text of knowing the rules of proportions, and how to render the "going of a male statue and the coming of a female statue . . . the convulsion of the single prisoner, the expression of fear on the face of enemies . . . the leg movements of one running." With this knowledge, he might have outlined the shapes of the hieroglyphs, remnants of which the stela still bears. Keeping the general shape of the hieroglyph while substituting the form of the palette, he renders the shape easily recognizable in a specific manner that shows his masterful knowledge of shapes and forms, both past and present.

Left: Haremhab as a Scribe of the King. New Kingdom, Dynasty 18, reign of Tutankhamun or Aya (ca. 1336–1323 B.C.). Granodiorite; H. 113 cm (44 1/2 in.), W. 71 cm (27 15/16 in.), D. 55.5 cm (21 7/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. V. Everit Macy, 1923 (23.10.1). Right: Detail view of base, showing "scribe" hieroglyph

A similarly sophisticated use of the hieroglyph for "writing" and "scribe" appears on the scribal statue of Haremhab. The archaic image of the scribal kit appears inscribed at the front of the statue and on the back of its shoulder, while its garment and style place it at Haremhab's here and now. The hieroglyph thus adjoins a composite image of its owner that mixes forms that are old and new, rendering a refreshingly innovative image of writing. I will discuss the statue of Haremhab's further in an upcoming Conversation with a Curator event on November 5.

Additional Reading

Allen, James P. The Heqanakht Papyri. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002.

Oppenheim, Adela, Dorothea Arnold, Dieter Arnold, and Kei Yamamoto. Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2015.

Parkinson, Richard B., and Stephen Quirke. Papyrus. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995.

Related Links

Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom, on view October 12, 2015–January 24, 2016

Now at the Met: "Welcome to Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom" (October 26, 2015)

Niv Allon

Assistant Curator Niv Allon received his PhD in Egyptology from Yale University in 2014. That same year, he joined the Museum's curatorial staff as a specialist in ancient Egyptian texts and scripts. Before joining the Museum, Niv took part in an international project on classification and classifying systems, and was awarded a Andrew W. Mellon Fellowship. Niv's scholarship probes the nexus of visual studies and textual analysis, investigating how art, sign, and language interact. He is currently working on a book on the relationship between the military and the visualization of literacy in New Kingdom Egypt. In addition, he is the co-author of a book on ancient Egyptian scribes.