Sacrifice, Fealty, and a Sculptor's Signature on a Maya Relief

Fig. 1. Relief with Enthroned Ruler, 8th century. Guatemala or Mexico, Mesoamerica. Maya. Limestone, paint; H. 35 x W. 34 1/2 x D. 2 3/4 in. (88.9 x 87.6 x 7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Michael C. Rockefeller Memorial Collection, Bequest of Nelson A. Rockefeller, 1979 (1979.206.1047)

«One of the Maya masterworks at The Metropolitan Museum of Art is an eighth-century relief with enthroned ruler, likely a fragment of the carved lintel of a doorway from the site of La Pasadita in northwestern Guatemala (fig. 1). La Pasadita was visited in the 1970s by renowned explorer and monument recorder Ian Graham, but subsequently became dangerous for scholarly visits because of border conflicts during the country's decades-long civil conflict. Land mines and security problems prevented archaeological work until 1998, when Charles Golden and colleagues performed reconnaissance in the area. Even today, the site lies within a troubled zone suffering the effects of narcotrafficking and illegal settlements within the national parks in the Usumacinta River drainage.»

In the eighth century, the small hilltop site of La Pasadita was embroiled in a different type of border conflict, caught between the power struggles of the self-proclaimed divine kings of the river kingdoms of Yaxchilan (modern-day Chiapas, Mexico) and Piedras Negras (Guatemala). During the Classic Maya period (ca. A.D. 250–900), the two major royal courts vied for power, paid tribute to one another, intermarried, and engaged in conflict with subsidiary local lords. Loyalties sometimes shifted, boundaries between the two city-states were often fortified, and artistic programs sponsored by the lords and ladies served as propaganda to stake claims on the contested landscape.

The Yaxchilan kings and queens favored elaborate sculpted doorway lintels at the royal capital, and they made sure their local allies marked their palaces in the same way. At least a dozen lintel reliefs such as the Met's masterpiece from La Pasadita are known from subsidiary sites around Yaxchilan. Likely commissioned by the Yaxchilan rulers themselves, most show the ruler from Yaxchilan in the company of the local lord in overt statements of sovereignty.

The Met's lintel shows three figures: one seated on the right, and two standing facing him to the left. The main figure, offering an elaborate headdress to the seated ruler, is the La Pasadita ruler named Tiloom (fig. 2), who ruled from approximately A.D. 750s–770s, using the title of sajal, a title for subsidiary regional governors. Tiloom appeared on at least three other known doorway sculptures: one in the Ethnologisches Museum in Berlin, dated to A.D. 759; one in the collection of the Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, dated to A.D. 766; and one in an unknown private collection, dated to A.D. 771. The Metropolitan's lintel is contemporaneous with that of the private collection, and was probably carved between A.D. 769 and the early 780s.

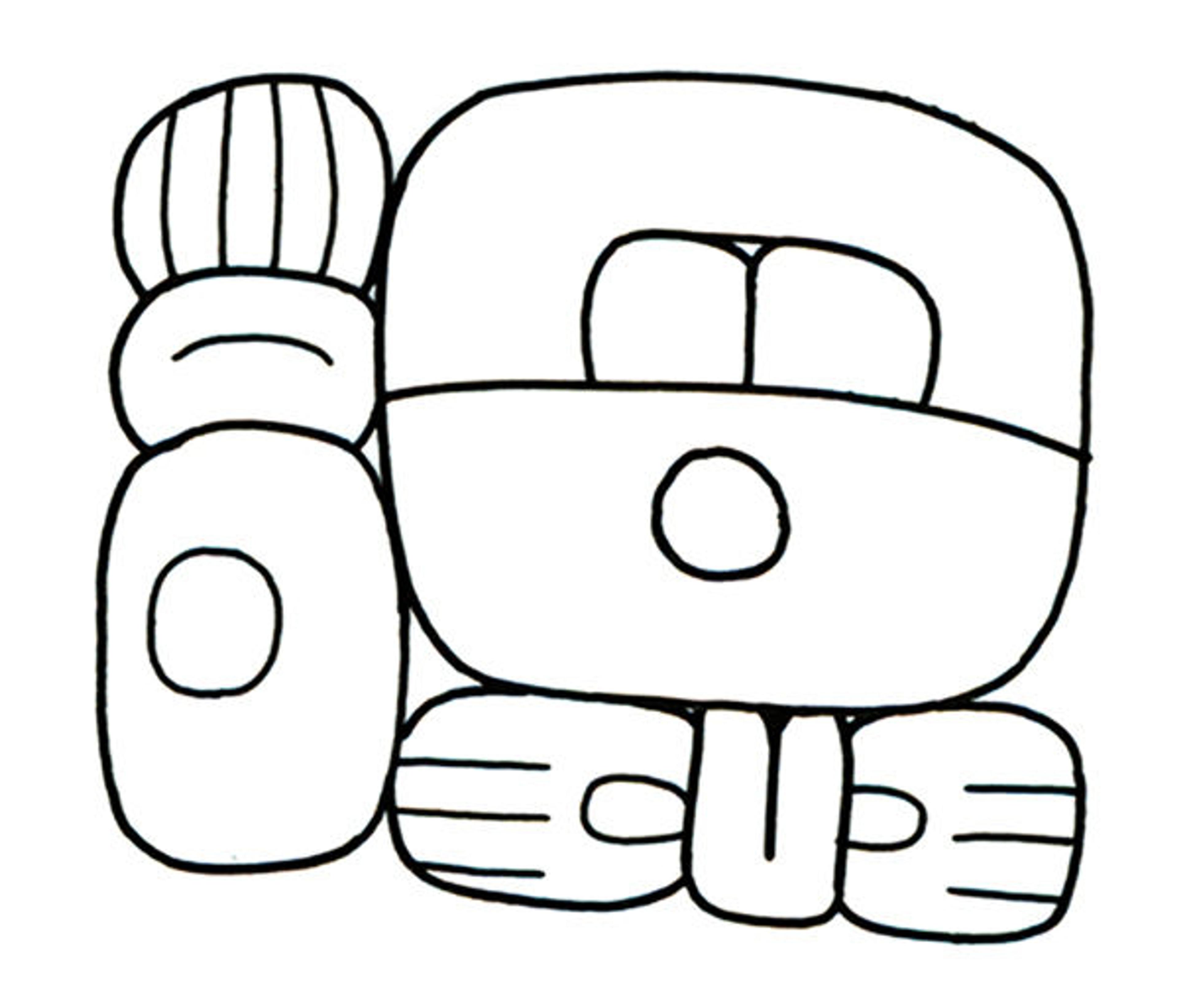

Fig. 2. Ti-lo-ma, or Tiloom, the name of the La Pasadita provincial ruler from the program of lintel sculptures. Drawing by Peter Mathews

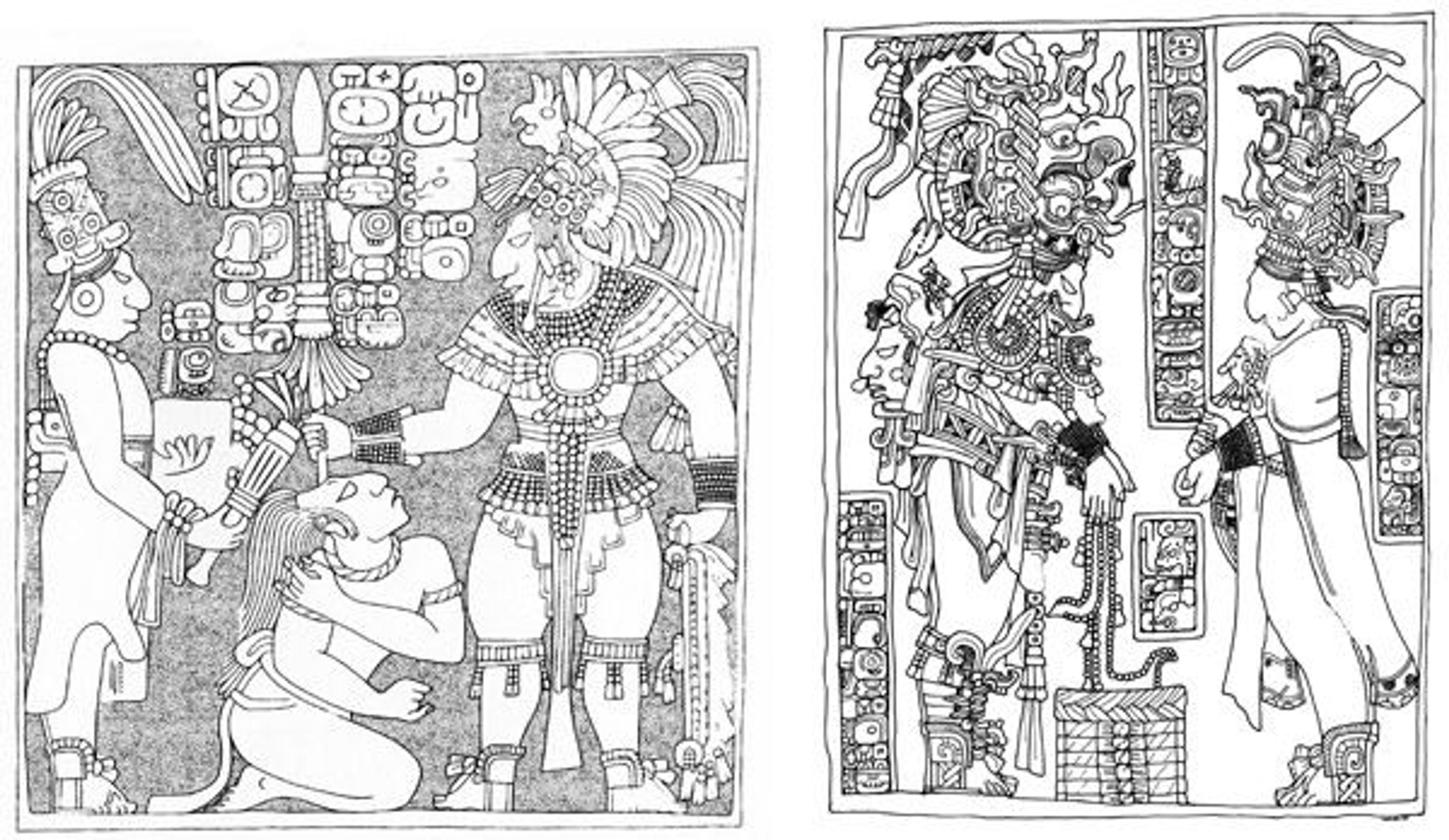

Tiloom was a loyal provincial ruler to the final two major kings of Yaxchilan—the father-and-son rulers of Bird Jaguar IV and Shield Jaguar III. Bird Jaguar IV ruled from A.D. 752 to 768, and Shield Jaguar III from A.D. 769 to around the turn of the ninth century. Bird Jaguar IV dominates the Berlin and Leiden lintels (fig. 3), in which Tiloom assists in a captive presentation and a scattering of incense, respectively. The "Sun Lord" captive pictured in the Berlin lintel is likely from Piedras Negras, and is the final portrayal of the many war victories of Bird Jaguar IV, who referred to himself as "he of twenty captives." In the Leiden panel, commemorating an event that occurred seven years after the Berlin captive-presentation scene, Tiloom assists Bird Jaguar IV with a "scattering" ritual in which the king drops blood or incense into a basket. The lintel from A.D. 771, in which Tiloom dances in a bird costume alone, perhaps signals a shift in authority from one overlord to the other; Tiloom celebrated his own right to rule, rather than his supporting role to the Yaxchilan king.

Fig. 3. Left: Lintel, 8th century. Guatemala, La Pasadita. Maya. Limestone, pigments; 96 x 89 x 5 cm. Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin (IV Ca 45530). Drawing by Ian Graham. Right: Lintel, 8th century. Guatemala. Maya. Limestone, pigments; 117.3 x 90.2 cm. Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden (3939-1). Drawing by Linda Schele

The Metropolitan's lintel also dates to the early 770s; in fact, the same sculptor carved the two lintels—an individual by the name of Chakalte'. Sculptors' signatures are relatively rare in Maya art, though many are known from the area around Yaxchilan and Piedras Negras. Chakalte' was probably a sculptor of Shield Jaguar III himself, who was known to send out sculptors to the other provincial lords, such as the rulers of the well-known site of Bonampak. Sculptors were sometimes important members of the royal courts; at Piedras Negras, it seems that a master sculptor oversaw an atelier of apprentices who all signed the same works. Many hands thus crafted these royal portraits.

The relief panel would have been installed parallel to the floor of the entrance of a temple at La Pasadita. Visitors to the building would have been forced to look upward to view the monument, and perhaps even had to light the surface with raking torchlight in order to read the image and the text. One of the distinguishing features of the Met's lintel is the striking amount of pigment preserved on the surface. A variety of red, yellow-orange, and blue-green pigment remains to give clues about the original brightly colored appearance of the lintels. The jade jewels of Tiloom and Shield Jaguar III and the details on the ruler's throne glisten in blue-green, a color that symbolized the "first/newest" and most precious materials.

Chakalte' composed the Met's lintel scene so that the visitor would be first greeted by the enthroned ruler, Shield Jaguar III, facing the interior of the structure. The king leans forward towards his visitors, wearing an elaborate feathered hair ornament, a feathered nose plug, and a beaded jade necklace with bar pendant. Tiloom then stands proudly, presenting the Yaxchilan holy lord with a headdress and what could be packets of incense or a plate of tamales. Tiloom wears a jaded headband and human-head pectoral, with an elaborate woven skirt that displays a geometric pattern. A third personage stands behind Tiloom in a similar outfit, but with a type of sombrero often associated with travelers or merchants in other scenes.

The text names the Yaxchilan "divine" lord with his preaccession name of Chel Te' Chan K'inich, which he changed to Shield Jaguar early in his reign because it was a namesake of ancestral rulers of the kingdom. The text naming Tiloom as the sajal, provincial lord, is squeezed in next to the ruler's arm and the offertory headdress, almost as if Chakalte' had not originally planned to include it. A bowl of sliced fruit with seeds visible sits under the throne, presumably part of the offering brought to the seated ruler.

The Metropolitan's lintel provides key information for the understanding of Classic Maya politics on the eve of institutional collapse at the end of the eighth century. It shows the final major Yaxchilan lord receiving tribute, in the form of food and regalia, from a lord that was loyal to his pugilist father known as the warlord of twenty captives. By the beginning of the ninth century, the dynasty at Yaxchilan ceased to build temples or commission monuments, thus silencing the voices of La Pasadita lord Tiloom and his sculptor of choice, Chakalte'.

Resources and Additional Reading

Bussel, G. W., and T. J. J. Leyenaar. Maya of Mexico. Leiden: The National Museum of Ethnology, 1991.

Freidel, David, and Linda Schele. Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. New York: William Morrow, 1990.

Golden, Charles W., Andrew K. Scherer, A. René Muñoz, and Rosaura Vásquez. "Piedras Negras and Yaxchilan: Divergent Political Trajectories in Adjacent Maya Polities." Latin American Antiquity, 19(3) (2008): 249–274.

Golden, Charles W., and Andrew K. Scherer. "Territory, Trust, Growth, and Collapse in Classic Period Maya Kingdoms." Current Anthropology, 54(4) (2013): 397–435.

Golden, Charles W. "Frayed at the edges: the re-creation of histories and memories on the frontiers of Classic period Maya polities." Ancient Mesoamerica, 21(2) (2010): 373–384.

Golden, Charles W. "The politics of warfare in the Usumacinta Basin: La Pasadita and the realm of Bird Jaguar." In Ancient Mesoamerican Warfare, edited by M. Katherine Brown and Travis W. Stanton, 31–48. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira, 2003.

Grube, Nikolai, and Marie Gaida. Die Maya: Schrift und Kunst. Berlin: SMB-Dumont, 2006.

Houston, Stephen. "Carving Credit: Authorship Among Classic Maya Sculptors" (paper presented at Making Value, Making Meaning: Techné in the Pre-columbian World, a Symposium at Dumbarton Oaks, 2013).

Martin, Simon, and Nikolai Grube. Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens. New York: Thames & Hudson, 2008.

Mathews, Peter. "Tilom." In Who's Who in the Classic Maya World. Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc., 2005.

Schele, Linda, and Mary Ellen Miller. The Blood of Kings: Dynasty and Ritual in Maya Art. Fort Worth: Kimbell Art Museum, 1986.

Simpson, Jon Erik. "The New York Relief Panel and Some Associations with Reliefs at Palenque and Elsewhere, Part 1." In Segunda Mesa Redonda de Palenque, edited by Merle Greene Robertson, 95–105. Pebble Beach: Pre-Columbian Art Research Institute, 1976.

James Doyle

James Doyle is an assistant curator in the Department of the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas.

Follow James on Twitter: @JamesDoyleMet