Jewelry and Power: Notes from a Friday Focus Lecture

«On Friday, January 9, the Department of Islamic Art, in conjunction with the Education Department, hosted guest lecturer Michael Spink to speak at a Friday Focus event. Spink's lecture, Jewelry and Power: Gold and Gems in Mughal India, illuminated the history of jewelry in the Mughal Empire and gave background information on the breathtaking gems that were displayed in the recently closed exhibition Treasures from India: Jewels from the Al-Thani Collection.»

Turban ornament (sarpesh), 1800–50. South India, Hyderabad. Gold set with diamonds, with hanging spinels of earlier date; enamel on reverse. The Al-Thani Collection. © Servette Overseas Limited 2013. All rights reserved.

Spink's lecture traced the changing relationship between the Mughal emperors and jewels, as well as the specific significance of certain gems to the ruling family. The first emperors, Babur and Humayan, were not attached to jewels. As they conquered northern India in the early sixteenth century, they usually gave away the gold and gems that they acquired. As a result, no jewelry survives from these first two reigns.

This changed once Humayan's son Akbar took the throne. Akbar began acquiring gems, and left a collection at his death estimated to be worth sixty million rupees. His son Jahangir continued collecting, and Jahangir's son, Shah Jahan, became a gem expert. The emperors had first pick of all the gems that came out of their mines and automatically took control of any jewel over five carats. After Shah Jahan's son Aurangzeb captured Golconda, the Mughals controlled the only known diamond mine in the world at that time.

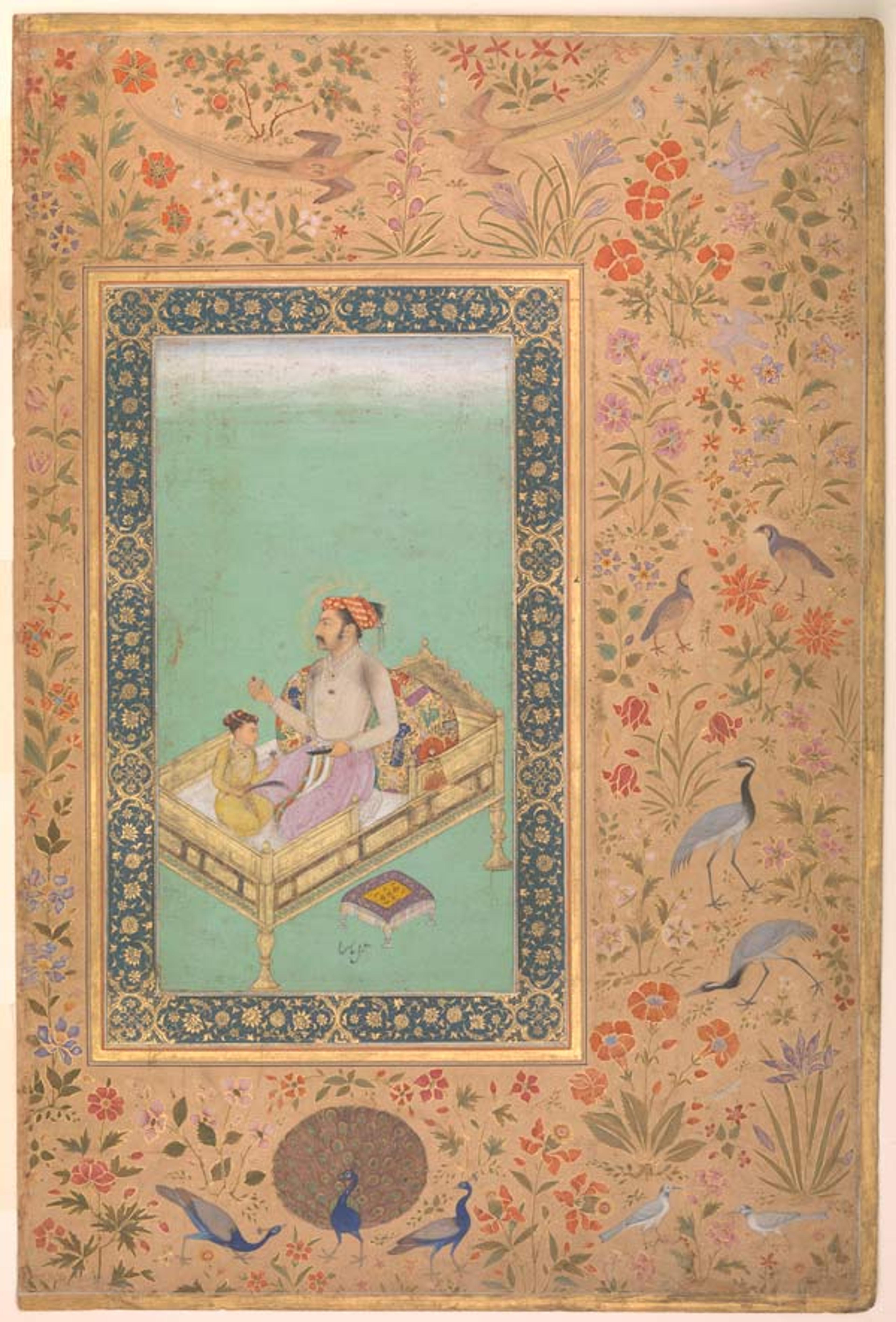

"The Emperor Shah Jahan with His Son Dara Shikoh," Folio from the Shah Jahan Album. Painting by Nanha, calligrapher Mir 'Ali Haravi (d. ca.1550). Verso: ca. 1620; recto: ca. 1530–50. India. Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; H. 15 5/16 in. (38.9 cm) x W. 10 5/16 in. (26.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund and The Kevorkian Foundation Gift, 1955 (55.121.10.36)

Spink outlined the four most important types of gems and their significance. Diamonds were considered the most important, and were prized for their clarity, beauty, and size. Rather than being cut down to enhance their sparkle, diamonds were kept as large as possible, often in asymmetrical cuts. The largest were over two hundred and fifty carats, and contemporary viewers compared them to eggs. Unfortunately, as the Mughal Empire declined, these gems were cut down, and Mughal diamonds can now be found in the collections of many royal families in Europe and Asia.

Emeralds were also highly valued. The Al-Thani Collection has a number of carved Mughal emeralds, most of which were mined in South America and brought to India to be carved and worn by the emperors. The Taj Mahal Emerald, which was on view in Treasures from India, would have been prized for both its size and the precision of its carving.

Taj Mahal Emerald. Emerald; H. 1 5/8 in. (4.1 cm) . W. 2 1/8 in. (5.4 cm). 141.13 ct. The Al-Thani Collection. © Servette Overseas Limited 2013. All rights reserved.

Spinels, or Balas rubies, were also highly prized. The emperor Jahangir popularized them, both for their beauty and because they were mined in his home province of Badakshan.

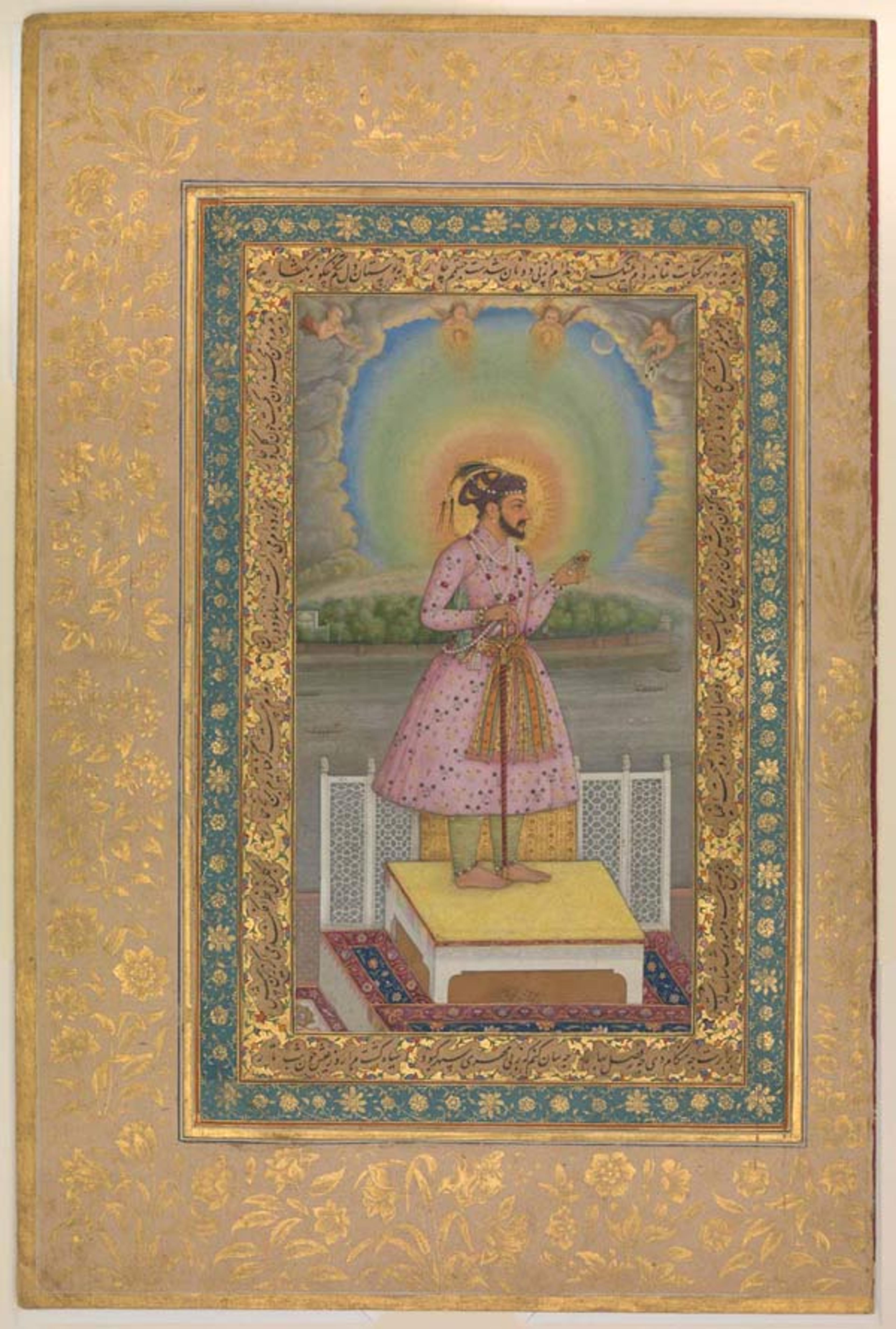

Finally, the Mughal emperors placed a great emphasis on pearls. Just like the other precious gems, the largest and most lustrous pearls were valued. The longest strands of pearls were reserved for the emperor and his sons. In the folio "Shah Jahan on a Terrace, Holding a Pendant Set with His Portrait," we see Shah Jahan draped in pearl necklaces that stretch down to his waist. This honor was reserved for only most highly ranked members of the royal family.

"Shah Jahan on a Terrace, Holding a Pendant Set with His Portrait," Folio from the Shah Jahan Album. Painting by Chitarman (active ca. 1627–70). Recto: 1627–28; verso: ca. 1530–50. India. Ink opaque watercolor, and gold on paper; H. 15 5/16 in. (38.9 cm) W. 10 1/8 in. (25.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund and The Kevorkian Foundation Gift, 1955 (55.121.10.24)

Jewels signified the worldly power of the emperors and connected dynastic lines, and names and dates were engraved on the gems that were passed down from emperor to emperor. Bejeweled swords and inkwells were given to high-ranking officials, demonstrating their importance to the empire as well as standing as a physical mark of favor.

Spink's fascinating lecture traced the relationship between the Mughal emperors and jewelry as well as the significance of the most valued jewels at the time. For more information on Mughal jewelry, please read Senior Research Assistant Courtney Stewart's blog post, "In the Stars: Gems and the Indian Tradition." Happy reading!

Related Link

MetMedia: Friday Focus—Jewelry and Power: Gold and Gems in Mughal India

Helen Goldenberg

Helen D. Goldenberg is an associate for administration in the Department of Islamic Art.