Food and Feasts in Middle Kingdom Egypt

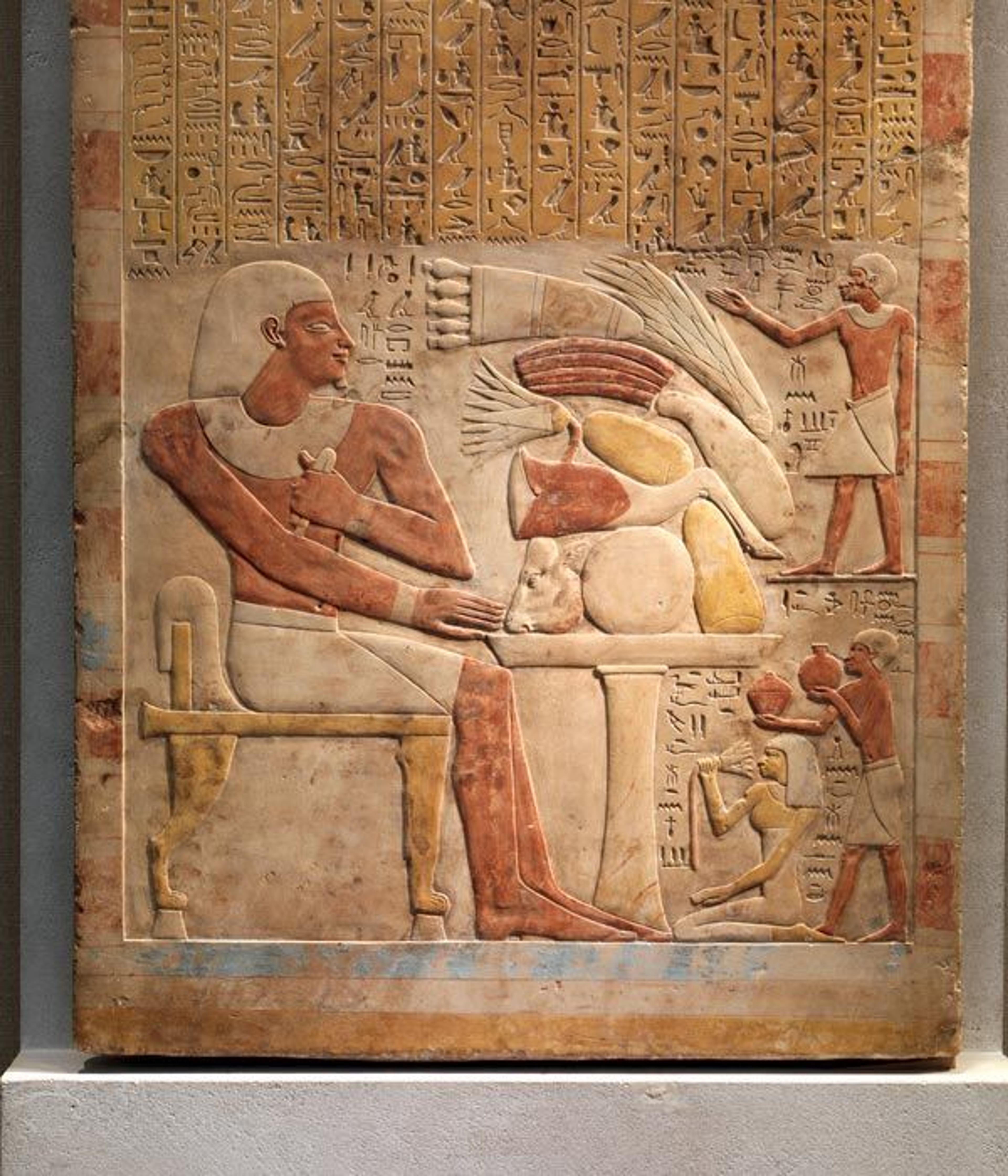

Stela of the Steward Mentuwoser (detail of lower half). Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Senwosret I, regnal year 17 (ca. 1944 B.C.). Northern Upper Egypy, probably Abydos. Limestone, paint; H. 103 cm (40 9/16 in.), W. 50.5 cm (19 7/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Gift of Edward S. Harkness, 1912 (12.184)

«Central to the Thanksgiving holiday in the United States is an elaborate, festive meal, which makes this week a perfect time to look at how ancient Egyptians feasted during the Middle Kingdom and how food is depicted in the exhibition Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom.»

The Middle Kingdom diet was largely restricted to native plants and animals, which were either domesticated or gathered from the wild. The large-scale importation of food so characteristic of our modern societies was not possible in ancient times, though at various points in Egyptian history new types of plants and animals were introduced. A wide variety of vegetables, fruits, and legumes were cultivated and consumed, including green onions, lettuce, dates, figs, and peas, the latter of which was introduced during the Middle Kingdom. These are depicted with meat and fowl in elegant and inventive compositions on stelas and tomb walls. In order to show the individual richness and overall quantity of the goods intended for the deceased, they are often shown floating in the air above tables.

A date palm tree in Egypt. Photo by the author

The staples of the Egyptian diet were bread and beer. Breads were made mainly with emmer wheat and baked into different shapes that included flat loaves, similar to pita bread, and long conical ones. Egyptian soldiers stationed in Nubian forts possessed inscribed, loaf-shaped wood tokens that specified the bread rations they would receive for a ten-day period. In a society that did not use coins or paper currency, food rations were often a form of payment for workers and household staff. Ancient Egyptian beer was quite different from the brews we consume today; thick and cloudy, it was an important source of nutrition rather than a purely enjoyable beverage, and it likely contained less alcohol than modern beers.

Round Military Ration Token. Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, reign of Amenemhat III (ca. 1859–1813 B.C.). From Sudan, Lower Nubia, Uronarti. Wood, paint; Diam. 13.1 cm (5 3/16 in.). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Harvard University-Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition (24.732)

Tomb scenes and three-dimensional models show cattle being slaughtered, while haunches of beef figure prominently in depictions of food offerings presented to the deceased; sheep and goats were also raised for their meat as well as their milk. The regular consumption of meat was likely reserved for the elite, while the poor ate it during festivals or other special occasions. Ducks and geese were captured in the marshes with clapnets and throw sticks, but also raised in captivity. Chickens seem to have entered the Egyptian diet in the fourth to fifth century, long after the Middle Kingdom had ended. (Turkeys, central to American Thanksgiving, are a bird of the New World.) Fish was also consumed, but not often depicted in scenes of offering or food production. More exotic creatures also found their way to the Egyptian table, including antelopes and hedgehogs.

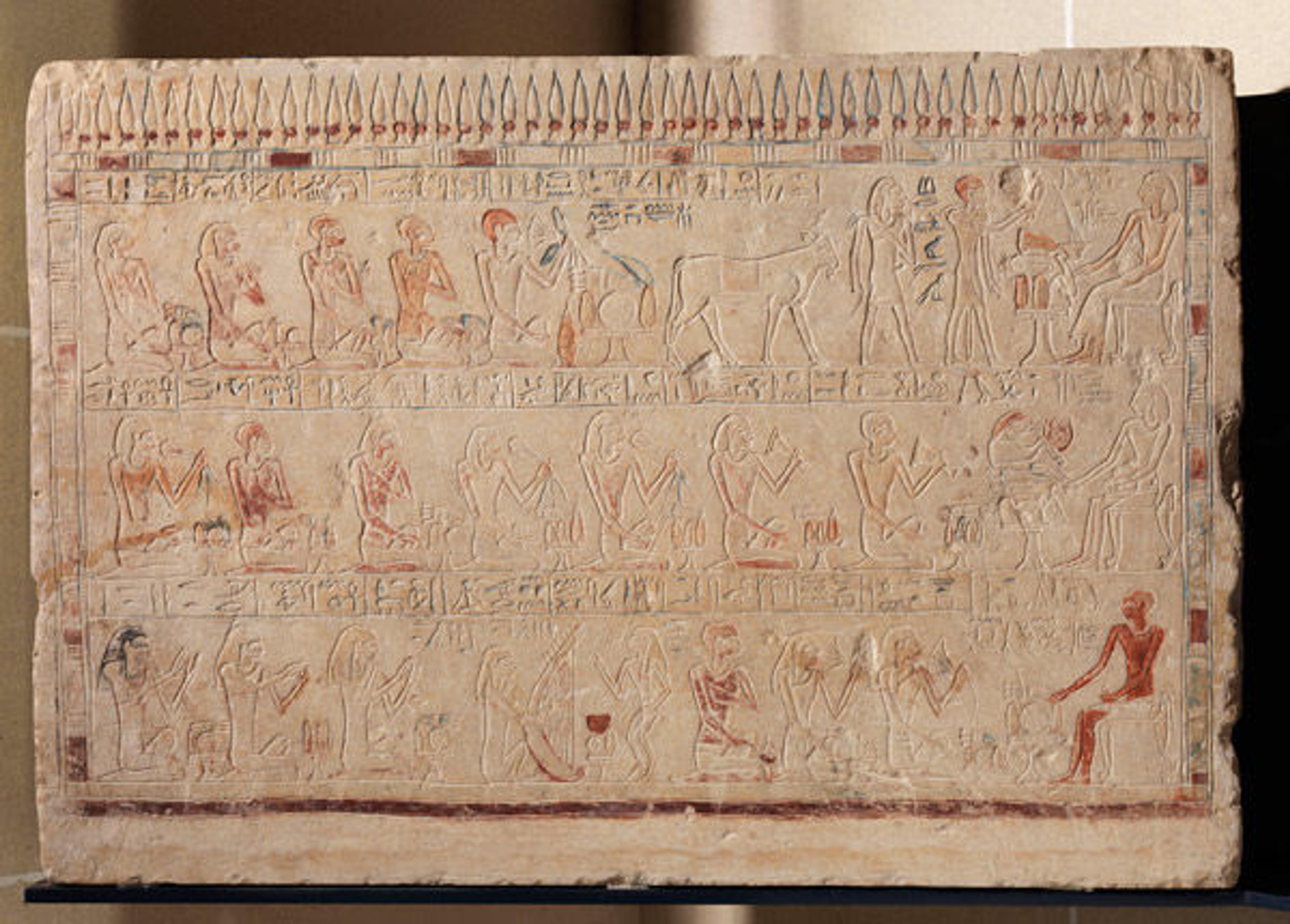

Left: Model of a Slaughter House. Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12, early reign of Amenemhat I (ca. 1981–1975 B.C.). From Thebes, Southern Asasif, Tomb of Meketre. Wood, paint, plaster; L. 76.8 cm (30 1/4 in.), W. 58.5 cm (23 1/16 in.), greatest H. 58.5 cm (23 1/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1920 (20.3.10). Right: Double-Sided Stela of the Priest Amenyseneb (view of one side depicting the cultivation and preparation of food). Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 13 (ca. 1802–1640 B.C.). From Abydos. Limestone, paint; 51 x 35 x 5.5 cm (20 1/16 x 13 3/4 x 2 3/16 in.). The Garstang Museum of Archaeology, University of Liverpool (E.30)

The ancient Egyptians believed that gods, goddesses, and deceased individuals—from the king to the common person—would need food and drink in the afterlife, just as they did in this life. Several methods were used to ensure that the deities and the deceased received sustenance. Most basic was the placement of actual food and drink offerings atop ritual tables decorated with depictions of these items, along with spells that a priest or worshiper would recite. The Egyptians realized that the dead or the gods would only symbolically consume these offerings, so after a period of time they were distributed to priests and others responsible for deity or mortuary cults.

Victuals were also placed in the tomb itself near the mummy. In the early Middle Kingdom, tombs could contain three-dimensional models that depicted such activities as storing grain, caring for cattle, slaughtering cattle, and making bread and beer. Finally, tomb chapels or temples included depictions of piled food offerings, individuals bringing food, and lists of products that would be provided to the deceased. With these various methods, the ancient Egyptians prepared for all contingencies: if food offerings were no longer presented, the depictions would suffice; if these were destroyed, stores of food still remained in the tomb itself.

Offering Table of the Overseers of Scribes Senbebu and Dedusobek. Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 12 (ca. 1981–1802 B.C.). Probably from Abydos. Limestone, paint; 16 x 49 x 50 cm (6 5/16 x 19 5/16 x 19 11/16 in.). Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, Leiden (AM 12-c)

The ancient Egyptians held feasts on a variety of occasions, most of which were connected to religious observances or commemorations of the dead. These banquets ideally featured large gatherings of family members and close associates, music and dance, and copious amounts of food. In many respects, it is likely that a Middle Kingdom festival bore some similarities to our own celebrations. This year, I hope that your Thanksgiving holiday will include a visit to see these depictions of four-thousand-year-old feasts in Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom, on view through January 24, 2016.

Slab from the Chapel of the Reporter of the Vizier Senwosret (view depicting a banquet). Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 13, reigns of Khaankhre Sebekhotep II to Userkare Khendjer (ca. 1802–1640 B.C.). Probably from Abydos. Limestone, paint; 54 x 78.5 cm (21 1/4 x 30 7/8 in.). Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Antiquités égyptiennes (N171)

Adela Oppenheim

Curator Adela Oppenheim received her BA from New York University, MA from the University of Pennsylvania, and PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, where she completed a dissertation on the decorative program of the Senwosret III pyramid temple at Dahshur. She co-directs (with Curator Dieter Arnold) the Museum's excavations at the Middle Kingdom pyramid complex of Pharaoh Senwosret III at Dahshur, where her work focuses on the relief decoration of the king's temples. Adela has written and lectured extensively on Middle Kingdom art and the results of the Dahshur excavations.