A Very Special Visitor: Albrecht Dürer's Woodblock for The Fifth Knot

Fig. 1. Installation view of a display case in the Fashion and Virtue exhibition containing an Italian engraving after Leonardo da Vinci's The Fifth Knot, Albrecht Dürer's woodblock for The Fifth Knot, and a posthumous impression of Dürer's The Fourth Knot

«The current exhibition Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620, on view through January 10, 2016, celebrates the first hundred years of the production of a new genre of popular booklets that distributed designs for textile decorations all over Europe. These textile pattern books were first printed in the 1520s, about twenty years after ornament and design had emerged as autonomous and very popular subjects in prints and books. This significant development is illustrated in the exhibition by a case study focused on a very special series of prints known as The Six Knots (figs. 1 and 2).»

Fig. 2. Installation view of a wall display in the Fashion and Virtue exhibition with Albrecht Dürer's rendition of The Six Knots in woodcut

The series originated from the mind of none other than the celebrated Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), who created the designs for the interlaced roundels while working in Milan in the 1490s. Interlaces were at the height of fashion at the Milanese court at this time, and were used across Italy as ornament on a great variety of objects—from miniatures and printed title pages, to earthenware (fig. 3), corded belts and belt buckles, compasses, sword hilts, gun barrels, chains, and bird cages.

Fig. 3. Dish (coppa umbonata), ca. 1530. Italian, Gubbio. Maiolica (tin-glazed earthenware); Diameter: 7 3/4 in. (19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.1072)

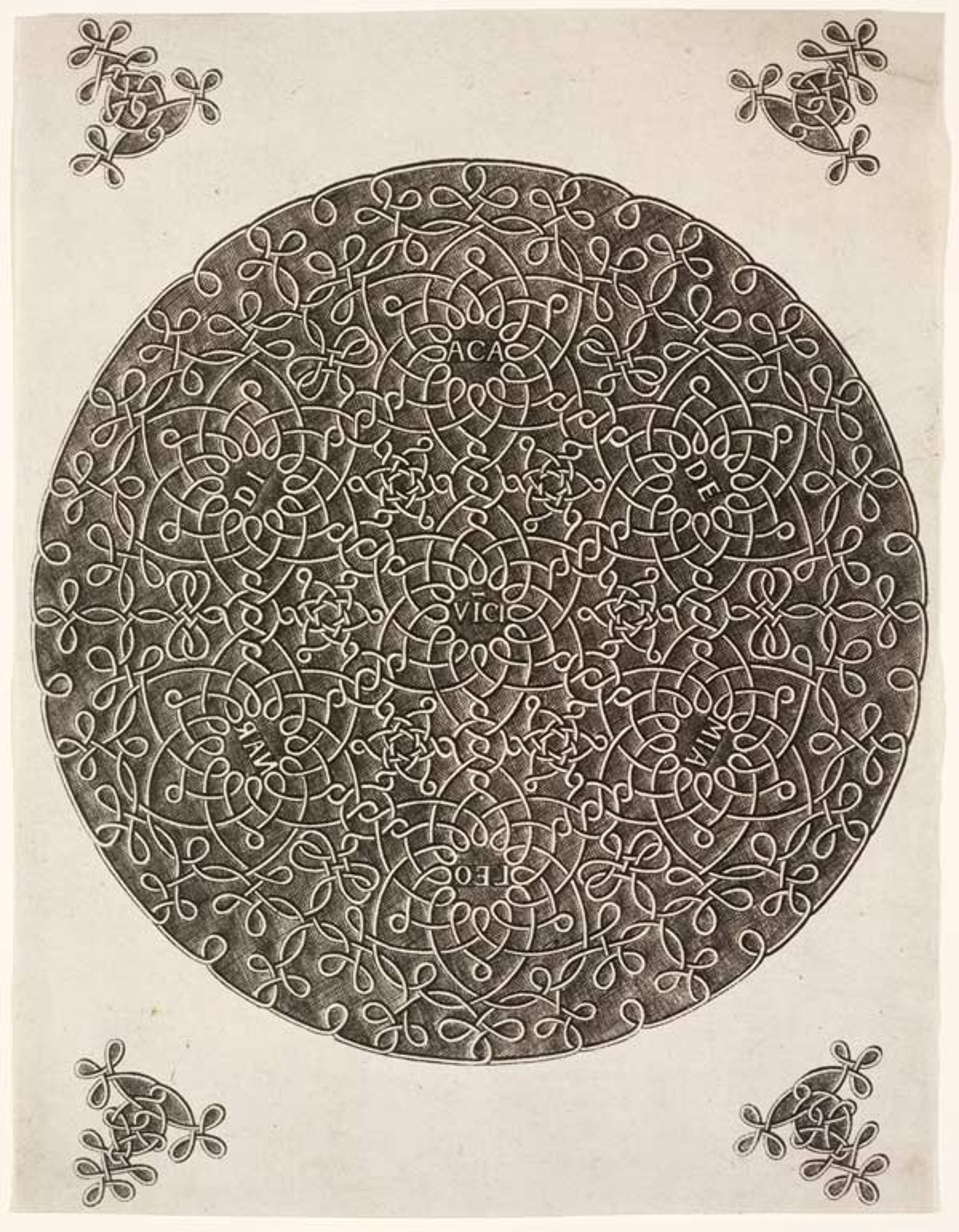

The great popularity of this type of ornament may have been one of the reasons why Da Vinci's designs were soon translated into a set of engravings by an unidentified artist in his circle. However, while prints are commonly known as a medium of multiples, it appears that only a limited number of these prints were executed. Only a handful survive today in museum collections, and the Met is fortunate to be able to include an example from the collection of the Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence, in the exhibition (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Attributed to Leonardo da Vinci (Italian, 1452–1519). The Fifth Knot, interlaced roundel with seven six-pointed stars, ca. 1498. Engraving; Plate: 10 3/8 x 7 13/16 in. (26.4 x 19.8 cm). Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence

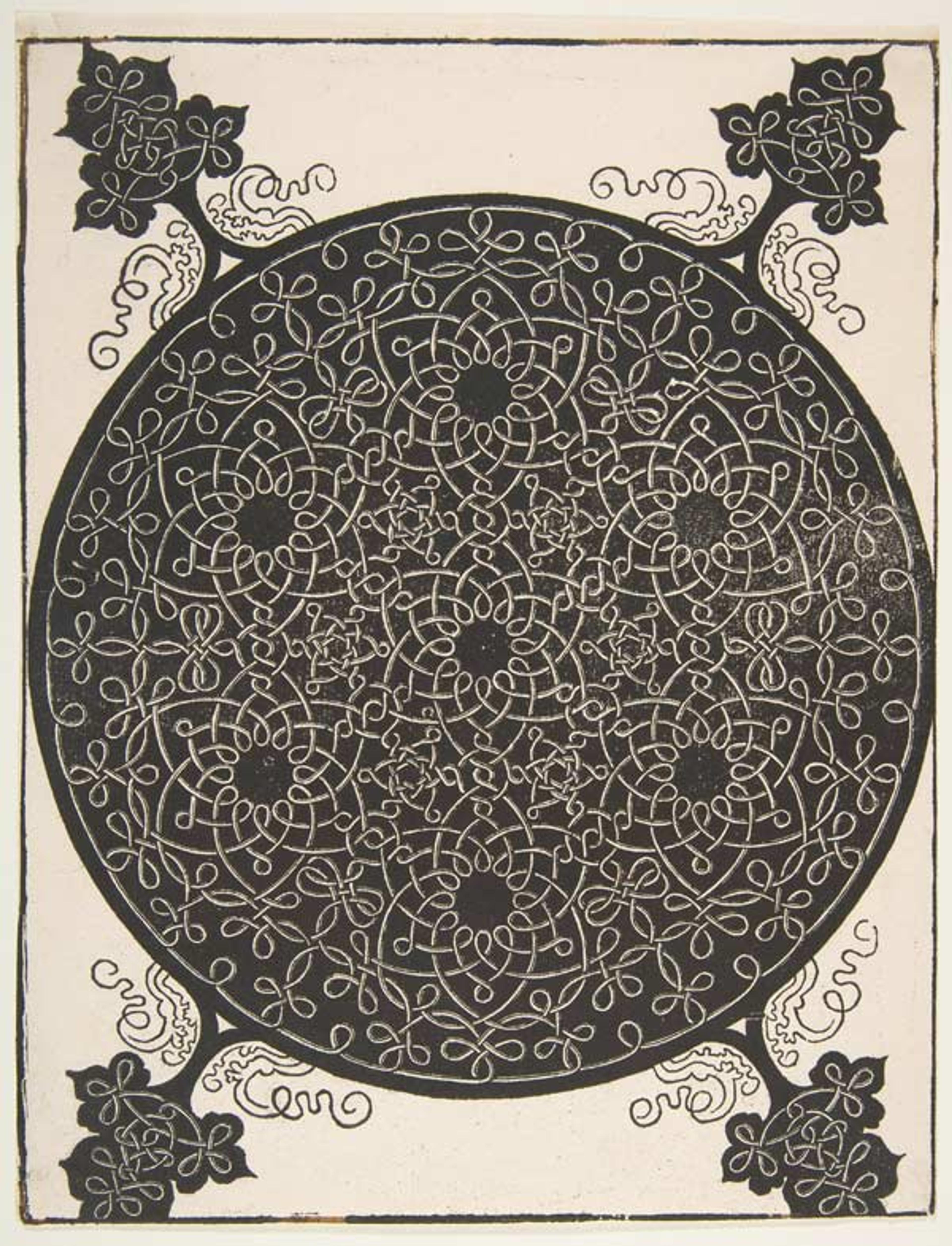

The idea that the Italian engravings were already rare during the Renaissance is supported by the fact that a set of copies in woodcut were created by none other than the northern print virtuoso Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528), who encountered the prints during a trip to Italy undertaken between 1505 and 1507. Copying after other artists was uncharacteristic for the famous artist from Nuremberg, but the ingenuity and appeal of these designs led him to set aside his scruples and create the woodcuts, to be able to share the beautiful designs with his northern colleagues (figs. 2 and 5).

Fig. 5. Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528). The Fifth Knot, interlaced roundel with seven six-pointed stars, before 1521. Woodcut; sheet: 10 3/4 x 8 3/16 in. (27.3 x 20.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, George Khuner Collection, Bequest of Marianne Khuner, 1984 (1984.1201.35)

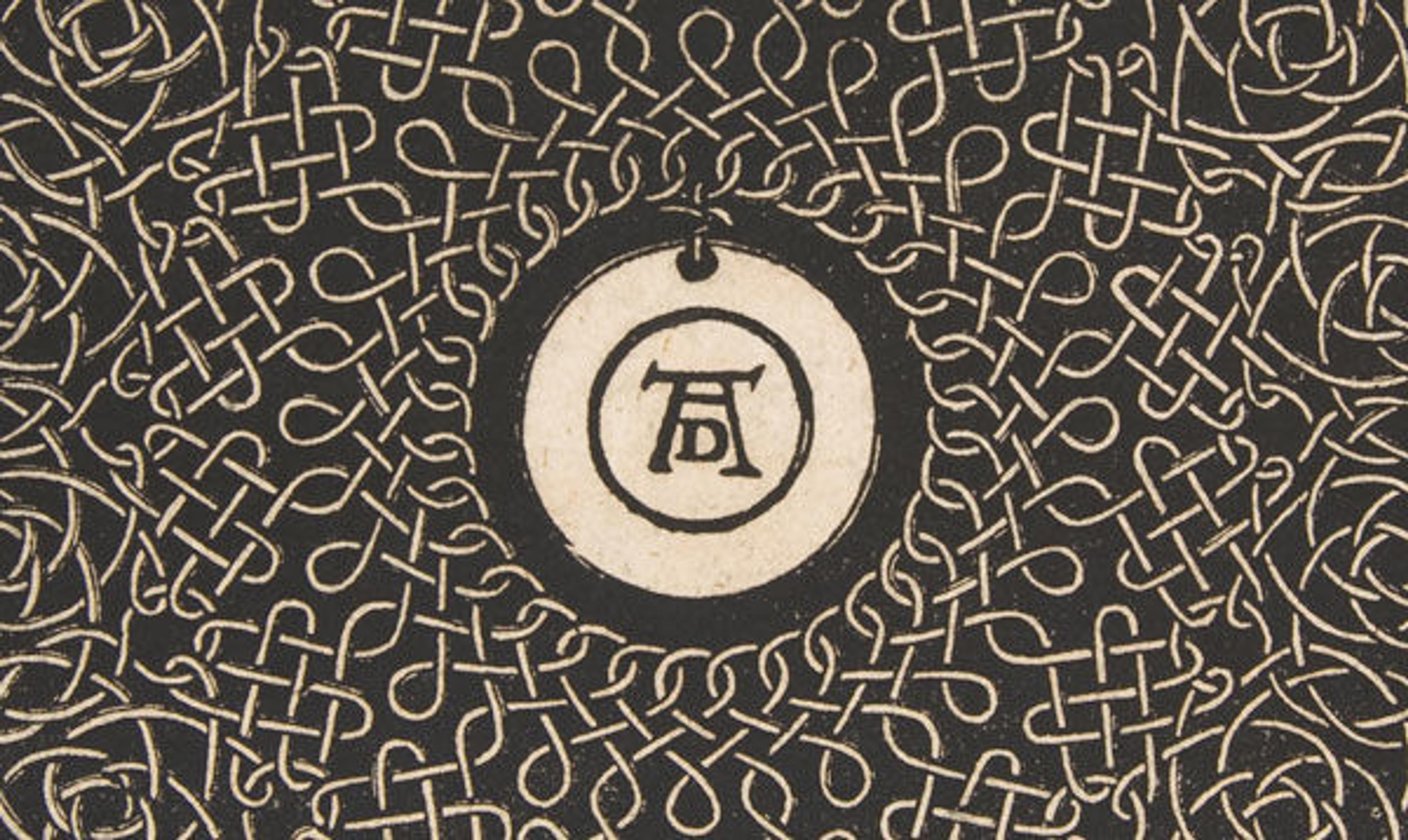

The woodcut series was popular, as is attested by the fact that they were still in print long after Dürer's death in 1528. The posthumous prints can be recognized by the addition of the artist's iconic initials, "AD" (fig. 6). Dürer himself had consciously chosen not to include this monogram in the prints, because he did not want to claim ownership of the designs of another artist. To stimulate sales, the subsequent owners of the woodblocks added the initials, which were likely printed from a separate small block.

Fig. 6. Albrecht Dürer's initials as printed in a posthumous impression of The Fourth Knot on view in Fashion and Virtue

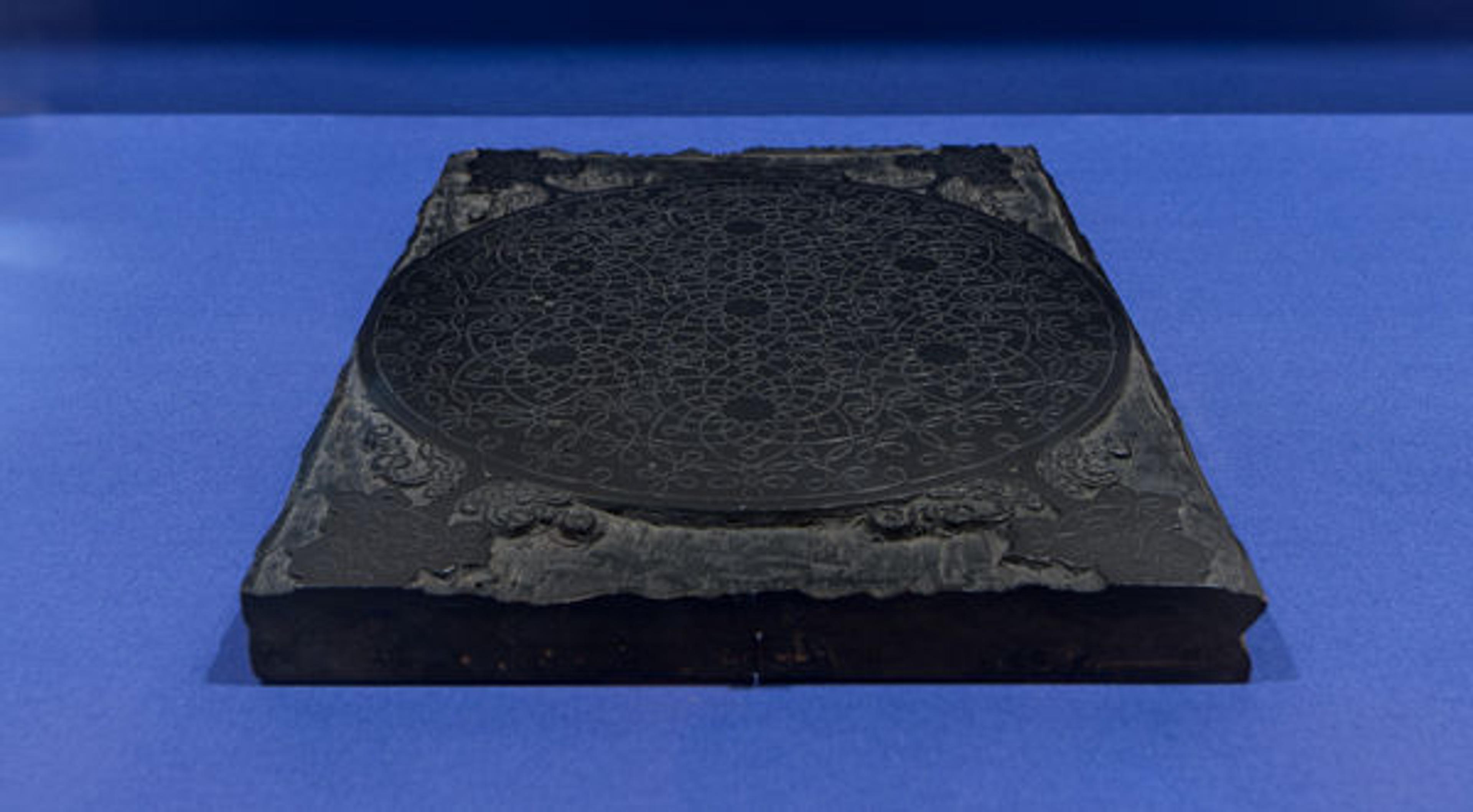

One of Dürer's original woodblocks survives to this day in the collection of Hans von Gersdorf (1630–1692), a very early collector of Dürer's printed works (fig. 7). Von Gersdorf reportedly purchased the woodblock for The Fifth Knot from the Amsterdam-based printer family Blaeu, who were well known for their maps and atlases. He took the block back to Germany, where it has remained since and is now housed at the Museum Bautzen.

Fig. 7. Close-up view of Albrecht Dürer's woodblock for The Fifth Knot, on loan from Museum Bautzen, Germany, as displayed in the exhibition Fashion and Virtue

The gracious loan of this woodblock to Fashion and Virtue signifies the first time since the late seventeenth century that the block has left its country of origin. It provides a unique opportunity for American art lovers to become acquainted, study, and enjoy this masterpiece of woodcarving, and to compare and contrast it with the delicate Italian engraving it was inspired by and the bold impressions it produced.

Related Links

Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620, on view October 20, 2015–January 10, 2016

Now at the Met: "A Happy Occasion for Melencolia I" (June 16, 2014)

Femke Speelberg

Associate Curator Femke Speelberg joined the Department of Drawings and Prints in 2011 and is responsible for ornament and architectural drawings, prints, and modelbooks. Her work focuses on the history of design and the transmission of ideas. Femke's research is inherently interdisciplinary, connecting works on paper with artworks, objects, and architecture from the fifteenth to the twentieth century. She often collaborates with other Museum departments on installations and publications. She has curated the exhibitions Living in Style: Five Centuries of Interior Design from the Collection of Drawings and Prints (2013) and Fashion and Virtue: Textile Patterns and the Print Revolution, 1520–1620 (2015).