The Art of the Chinese Album

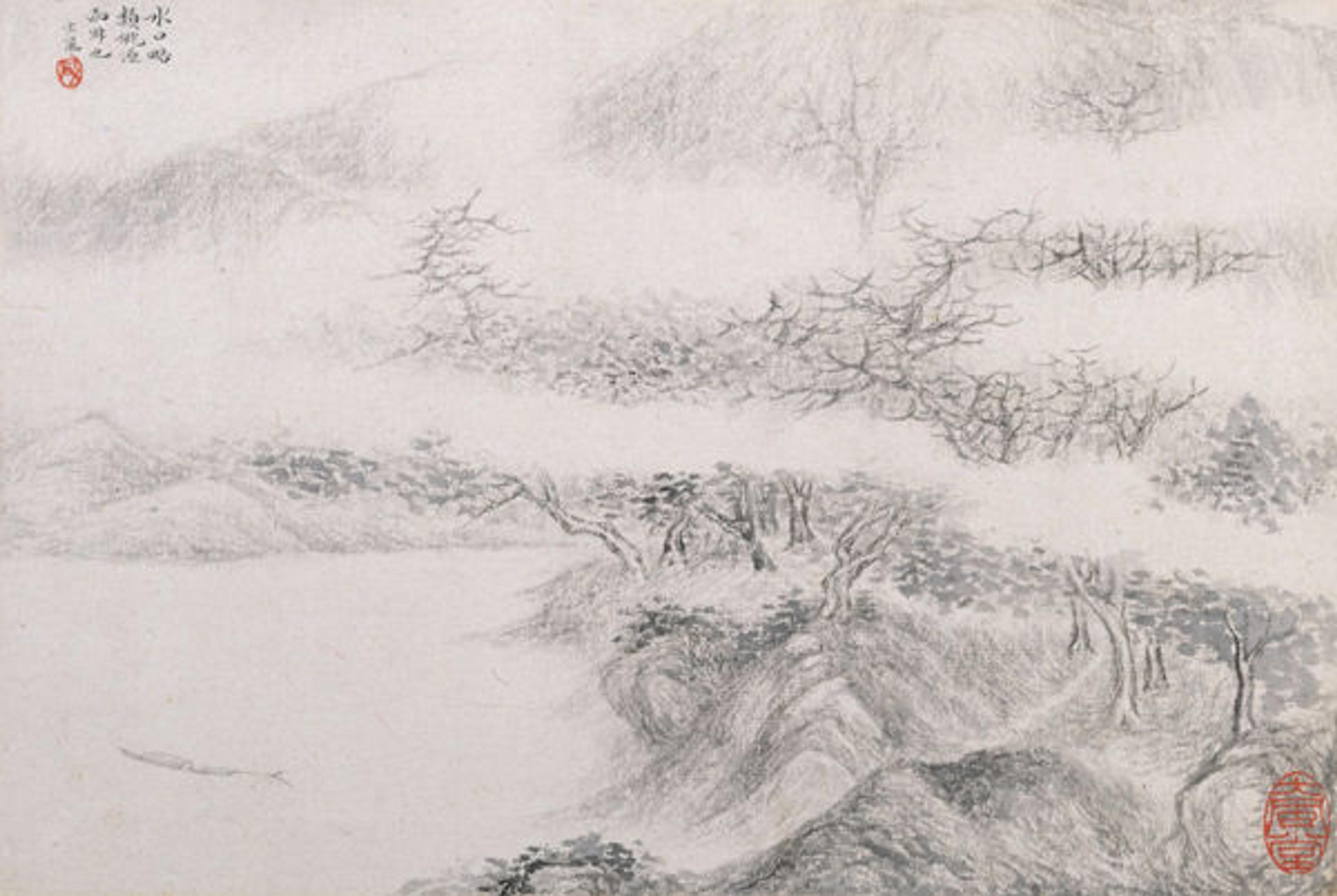

Fig. 1. Zhang Feng (Chinese, active ca. 1628–1662). Landscapes, dated 1644. Ming dynasty (1368–1644). One leaf from an album of twelve leaves; ink and color on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward Elliott Family Collection, Gift of Douglas Dillon, 1987 (1987.408.2a–n)

«During the summer of 1644, the city of Nanjing lived beneath a cloud of anxiety and fear. The once-vibrant southern capital of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) had become home to the remnants of the Ming court, a bedraggled and shaken group who had fled south after the fall of Beijing in April of that year. The shock of seeing their capital fall, of witnessing their young emperor retreat behind the Forbidden City and commit suicide—these were the traumas that the court brought south to Nanjing. Even as they struggled to establish a temporary capital in the south, up north the Manchus prepared to complete their conquest of the empire. Like a city preparing for the arrival of a hurricane, Nanjing waited, and feared.»

In this fraught moment, the artist Zhang Feng (active ca. 1628–1662) made a small, exquisite work of art (figs. 1–5). Painted in Nanjing in August 1644, Zhang's album Landscapes is a touching and perhaps surprising response to the trauma of dynastic upheaval. Landscapes consists of twelve small painted sheets of paper that depict remote and mostly unpopulated places. Throughout, Zhang Feng applies ink with a graceful, feather-light touch, confining himself to a restricted register of medium ink tones, from which he nevertheless manages to wrest enormous variety through subtle variations. For a work of art made in a loud, scary, chaotic moment, Landscapes speaks in a beautiful whisper. Yet, if we attune our ears, we can discern a powerful message.

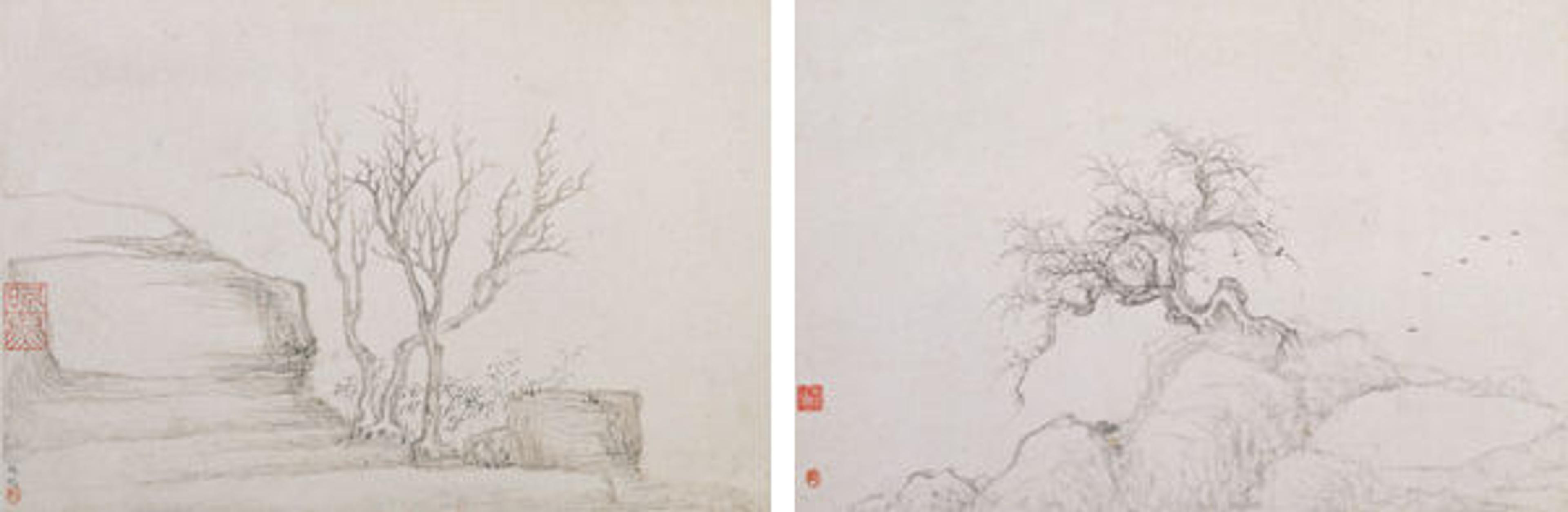

Figs. 2 and 3. Zhang Feng (Chinese, active ca. 1628–1662). Landscapes, dated 1644. Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Two leaves from an album of twelve; ink and color on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward Elliott Family Collection, Gift of Douglas Dillon, 1987 (1987.408.2a–n)

The first leaf sets the tone for the album (fig. 1). It depicts a fisherman's skiff floating in a stream near a mysterious inlet, an image that for viewers of Zhang Feng's day immediately would have called to mind "The Peach Blossom Spring," a beloved poem about a paradise removed from the strife of the mortal world. The image suggests an escapist vision, but Zhang's straightforward inscription—"This looks like Peach Blossom Spring, but it isn't"—seems to deny the possibility of escape.

Figs. 4 and 5. Zhang Feng (Chinese, active ca. 1628–1662). Landscapes, dated 1644. Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Two leaves from an album of twelve; ink and color on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Edward Elliott Family Collection, Gift of Douglas Dillon, 1987 (1987.408.2a–n)

Other leaves depict bleak, denuded landscapes (figs. 2, 3) or visions of reclusion (figs. 4, 5). Leafing through the album, one is confronted by a succession of delicate and carefully wrought images, each of which expresses a desire for a world beyond the reach of trouble—and the difficulty of finding such a place. It is a story of the battle between hope and despair, told through a series of linked pictures and ideas. In 1644 and the wrenching years that followed, this album, read on a table or simply held in the hands of a viewer, would have been a resoundingly resonant work of art, its tiny size belied by its outsized impact.

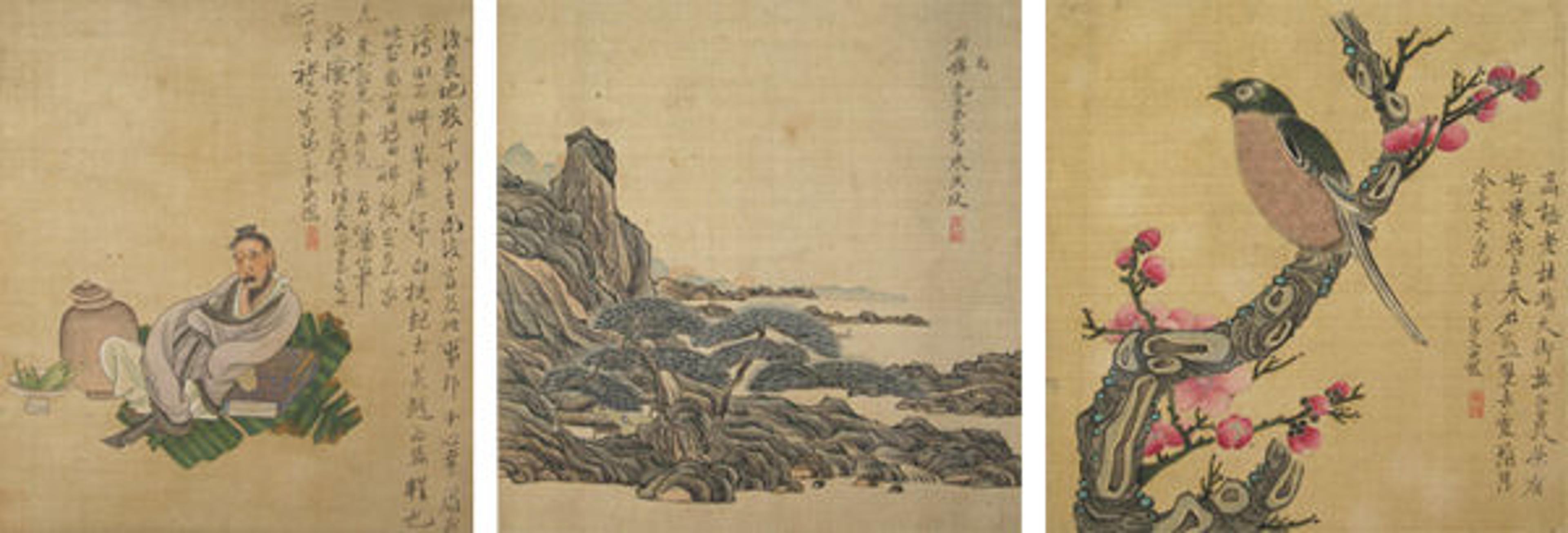

Figs. 6–8. Chen Hongshou (Chinese, 1599–1652). Figures, flowers and landscapes, one leaf dated 1627. Late Ming dynasty (1368–1644)–early Qing (1644–1911) dynasty. Three leaves from an album of eleven; ink and color on silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Wan-go H. C. Weng, 1999 (1999.521a–k)

Zhang Feng's Landscapes is a key piece in The Art of the Chinese Album, a new exhibition that introduces viewers to the special qualities of the album, one of the most intimate formats of Chinese painting. An album consists of a set of images brought together either by an artist or a collector into a book-like form. Some, like Zhang's Landscapes, deal with one consistent genre or theme, while others, like Chen Hongshou's (1599–1652) Figures, flowers, and landscapes shift wildly in subject matter from leaf to leaf, demonstrating the artist's versatility (figs. 6–8).

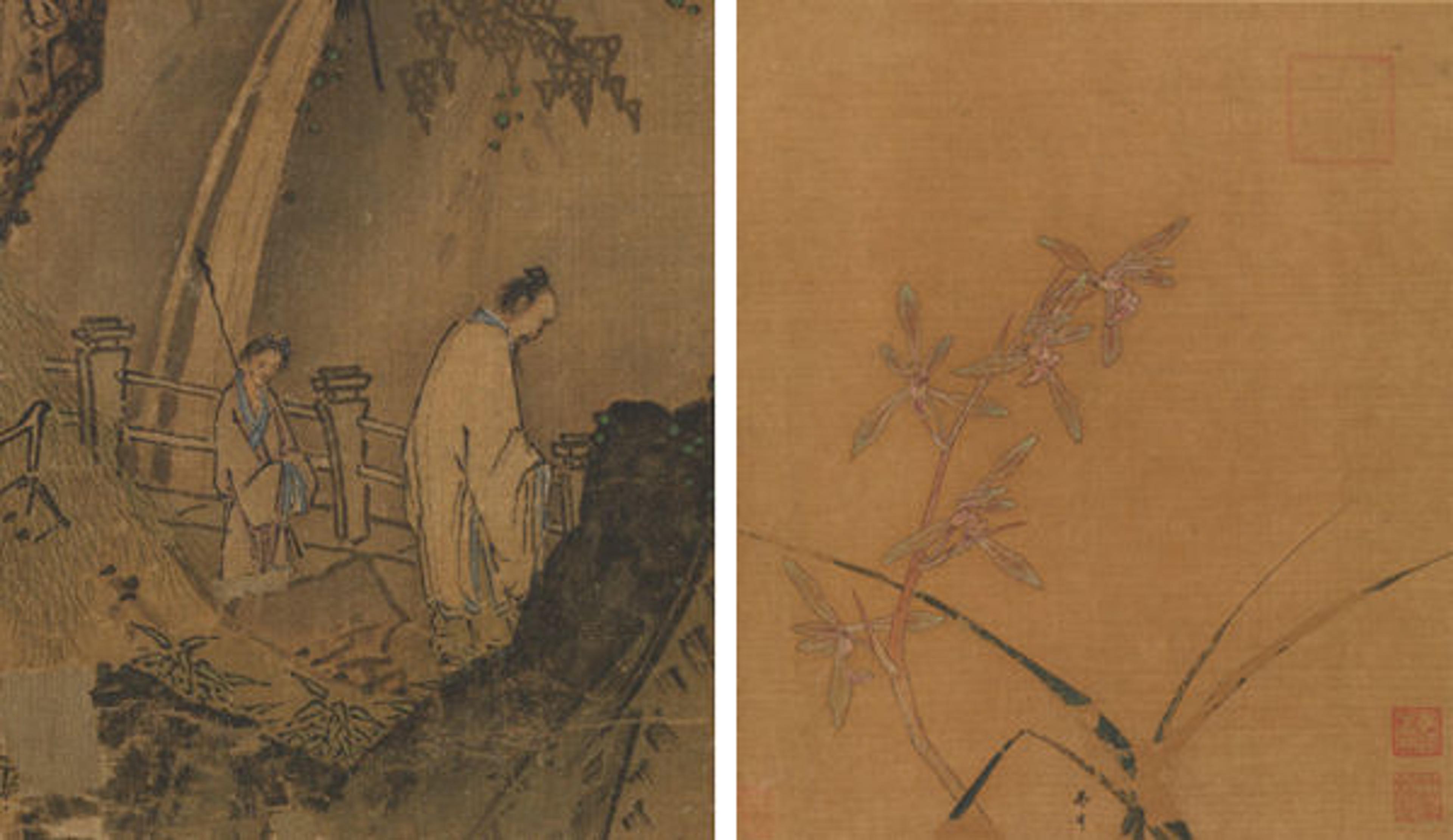

Figs. 9–11. Shitao (Zhu Ruoji) (Chinese, 1642–1707). Returning Home, ca. 1695. Qing dynasty (1644–1911). Three leaves from an album of twelve; ink and color on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, From the P. Y. and Kinmay W. Tang Family, Gift of Wen and Constance Fong, in honor of Mr. and Mrs. Douglas Dillon, 1976 (1976.280a–n)

Shitao's (1642–1707) Returning Home, the touchstone masterpiece of the exhibition, shifts back and forth between broad views of landscape and extreme close-ups of flowers, taking the viewer on a rollercoaster ride between two modes of viewing (figs. 9–11). These albums are more than just the sum of their parts; they are complex, multi-phased works of art, journeys to be taken by the viewer under the guidance of the artist.

Fig. 12 (left). Ma Yuan (active ca. 1190–1225). Scholar viewing a waterfall (detail), late 12th–early 13th century. Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). Album leaf; ink and color on silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ex coll.: C. C. Wang Family, Gift of The Dillon Fund, 1973 (1973.120.9). Fig. 13 (right). Ma Lin (ca. 1180–after 1256), Orchids, second quarter of the 13th century. Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279). Album leaf; ink and color on silk. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Ex coll.: C. C. Wang Family, Gift of The Dillon Fund, 1973 (1973.120.10)

The Art of the Chinese Album features more than sixty works of painting and calligraphy, most of which are drawn from the Met's permanent collection. The exhibition begins with several works from the Southern Song dynasty—including masterpieces by the court artist Ma Yuan (fig. 12) and his son Ma Lin (fig. 13)—but it is particularly rich in works of the seventeenth century, when a critical mass of gifted artists expanded the creative horizons of the album format. Among these are works by Dong Qichang (1555–1636), Gong Xian (1619–1689), Dai Benxiao (1621–1693), Zheng Min (1633–1683), Shitao, Chen Hongshou, and more. Above all, the exhibition aims to communicate the wonder, suspense, and excitement of flipping through an album by a great artist, where each turn of the page brings a new world of possibilities.

Related Link

The Art of the Chinese Album (on view through March 29, 2015)

Joseph Scheier-Dolberg

Joseph Scheier-Dolberg is an assistant curator in the Department of Asian Art.