Detectives at The Met: Looking at Paintings Through the Eyes of a Scientist

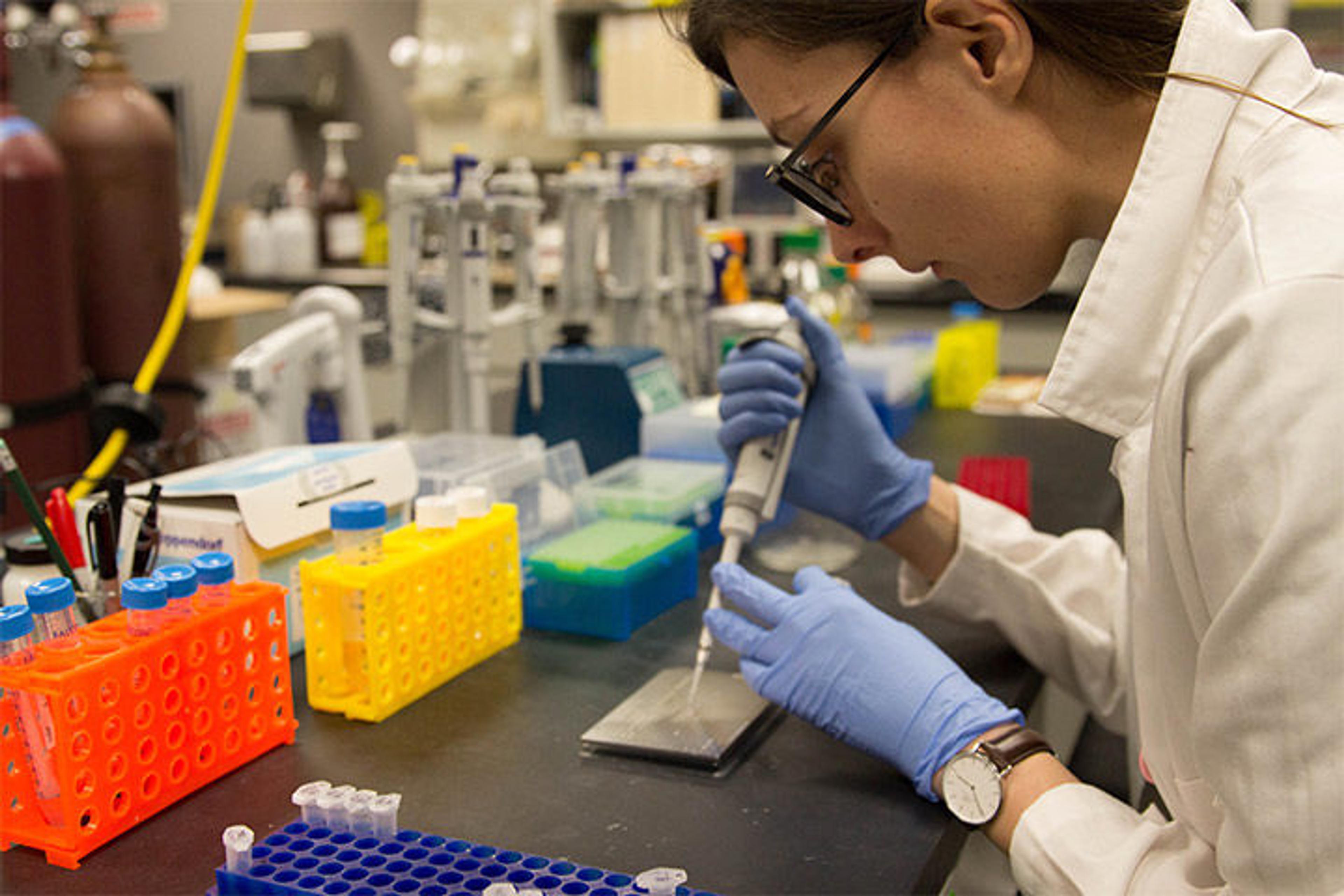

Clara using a pipette to put samples onto a metal plate for testing. Photo by Skyla Choi

Artists of the past used all kinds of different materials to make art, and it is up to the scientists in the Department of Scientific Research at The Met to try to identify them. It may be hard to believe, but there are real scientists hidden in the Museum! They are detectives dedicated to studying the materials and techniques used to create an artwork in order to better understand its story and try to lengthen its life. Each morning, the scientific detectives put on gloves and lab coats, turn on different instruments with really complicated names, and begin studying paintings, statues, textiles, and all of the other types of artworks in The Met collection. Their work is important because most of the artworks at The Met were made by artists who are no longer living.

«Every museum scientist dreams of speaking directly to the artists in order to ask them to reveal their secret techniques. As a fellow in the Department of Scientific Research, I wondered what it would be like to travel back in time 500 years ago to Florence, Italy, and speak with the Italian painter Sandro Botticelli. This is how I thought our interview might go:»

Clara Granzotto: Good morning, Sandro. It is nice to meet you and be back in the Renaissance! We are really impressed by your technique and the way you used art materials to paint The Annunciation. Can you speak a little bit on how you painted it?

Sandro Botticelli: Sure. I am glad The Met has paintings I made! I painted The Annunciation with eggs in 1485.

Sandro Botticelli (Italian, 1444/45–1510). The Annunciation, ca. 1485. Tempera and gold on wood, 7 1/2 x 12 3/8 in. (19.1 x 31.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Robert Lehman Collection, 1975 (1975.1.74)

Clara Granzotto: You painted with eggs? How is that possible?

Sandro Botticelli: Yes, with eggs! The technique is called "egg tempera," and it has been used since ancient Egyptian times. It is easy for me to go to the farm and get some eggs, not only for dinner but also to paint. I normally mix egg yolk with pigment powder and apply the color with a brush. Once the egg yolk dries, the paint film is waterproof, and it will resist for centuries!

Clara Granzotto: That is incredible. Did you know that we now have some techniques that allow us to see if you painted with egg or oil, or with egg yolk or egg white? There are no secrets scientists can't unveil!

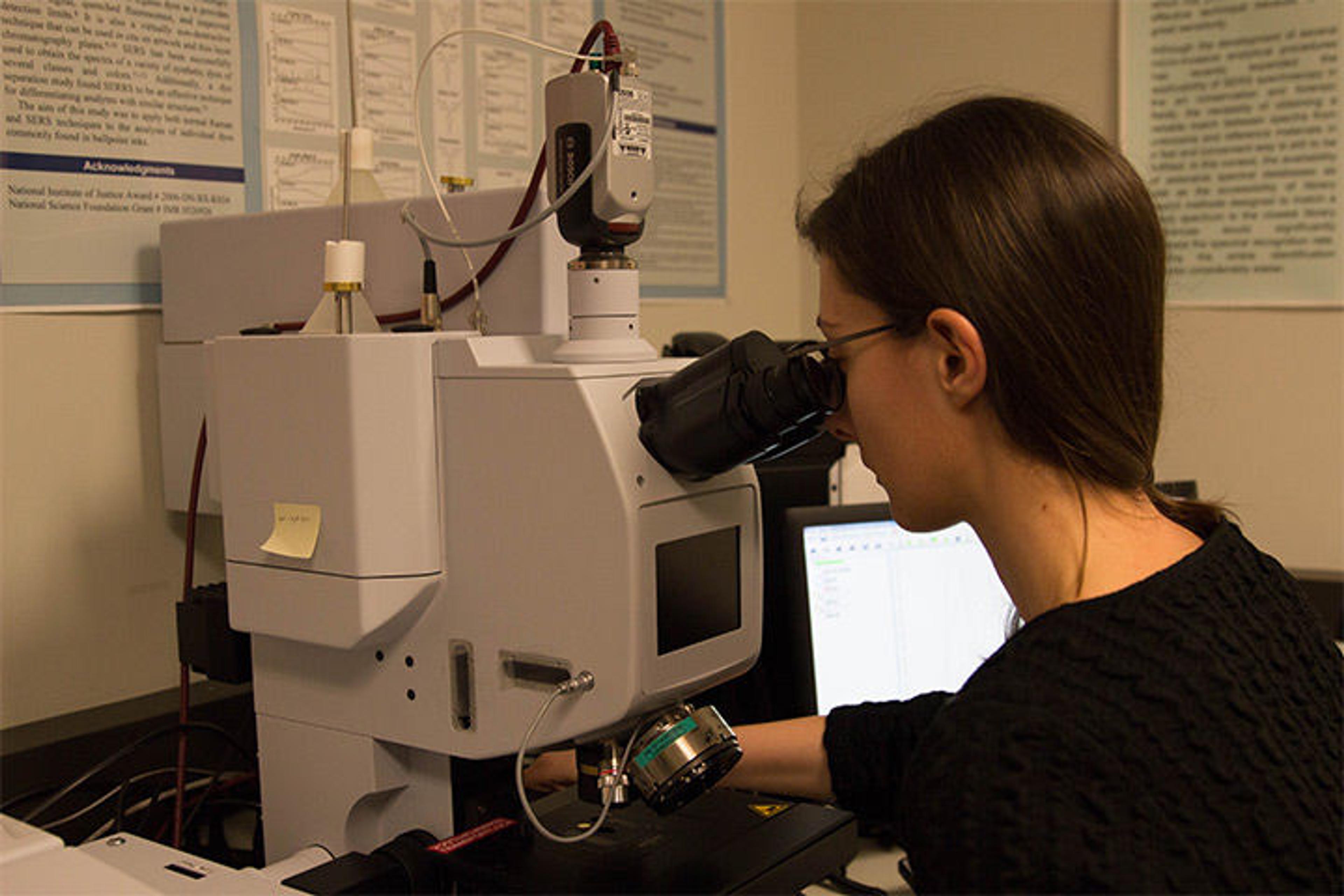

Clara using a Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Microscope to discover what materials were used in paints. Photo by Skyla Choi

Sandro Botticelli: Really? Well, I prefer the old fashioned way of looking carefully at the surface of a painting. If the cracks on a painting look like the skin of a crocodile, with squares, that shows that egg was used. If the cracks look like a spider web, it is an oil painting.

Clara Granzotto: That's a great idea! Eggs aren't the only kind of food that can be used to paint. Is it true that artists can use milk?

Sandro Botticelli: Yes, I am not a fan of it, but my friend Leonardo da Vinci experiments with using milk in mural paintings. I love milk with cookies, so I never have any left with which to paint.

Clara Granzotto: In our time, most painters use canvas—a strong, tightly woven fabric—as a support for paint. Do you use canvas?

Sandro Botticelli: No, I use wood panels! If you look carefully at my painting in 2017, you will see the wood because it becomes warped and bent after 500 years. In Europe, wood became a popular support for painting from the beginning of the Middle Ages, around 500 A.D., through the Renaissance, which ended around 1525 A.D. Starting in the 1500s, wood was almost entirely substituted with canvas. In Renaissance Italy, we often use poplar, which is a type of tree that grows here. Other Renaissance artists in other European countries use different kinds of native woods, like pine in Germany and oak in Holland! Wood is an easy material to find.

Clara Granzotto: Wood is so inhomogeneous, or made of different materials and not smooth. How can you paint on it?

Sandro Botticelli: We have a trick! Before we begin to paint, we usually apply a ground layer, which creates a smooth surface. In my time, we usually mix gypsum, or a white mineral, with animal glue and apply this paste over the wood so we have a clear, white background.

Clara Granzotto: And then you draw the subject, right? Nowadays we have a special technique called infrared reflectography, which allows us to take a picture of what is behind the paint layers. We call this the underdrawing, and we actually can see if a painter changed their mind while drawing!

Sandro Botticelli: There are no secrets scientists can't uncover! I love to draw with a liquid medium, but, like drawing with a pen, it is hard to erase, so I often use a stick of charcoal at the beginning. That way it is easy to erase mistakes by dusting the charcoal off. Some of my friends use the back of the brush to carve into the ground layer when it is still wet, but then it dries and you can't erase!

X-radiograph of Botticelli's The Annunciation. Image courtesy of the Department of Paintings Conservation

Clara Granzotto: Thanks, Sandro! We have learned a lot today about how a painting is made and the materials that painters from the Renaissance used.

Sandro Botticelli: You are welcome! Now you can see artworks from a different point of view. Have fun in the Museum!

Now you, too, can be a detective in the Museum. Look at the surface of a painting and try to determine what material the painter used. Then, look at the label to see if you are right. Now imagine what the painting's underdrawing might look like. Let us know what you discover, and share what you think is hidden underneath the layers of paint!

Clara Granzotto

Clara Granzotto is a fellow in the Department of Scientific Research.