Sounds of The Cloisters: A New Refectory Bell

Refectory bell, 13th century. German. Copper alloy; 9 13/16 x 13 3/4 in., 50 lb. (24.9 x 35 cm, 22.7 kg). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Cloisters Collection, 2014 (2014.87)

«The Cloisters recently acquired a rare medieval refectory bell that is now installed in the Cuxa Cloister outside the Chapter House from Notre-Dame-de-Pontaut. Smaller than the taller and more familiar church bells usually suspended in bell towers, this bell was probably made for a monastic refectory, or dining hall. Cast in copper alloy using the lost-wax method, it is inscribed with the words Tinnio pransvris cenatvris bibitvris, which translates to "I ring for breakfast, dinner, and drinks." In addition to the inscription, the bell is decorated with roundels depicting two angels, a winged lion, and the Agnus Dei, or Lamb of God.»

A view of the underside of the refectory bell

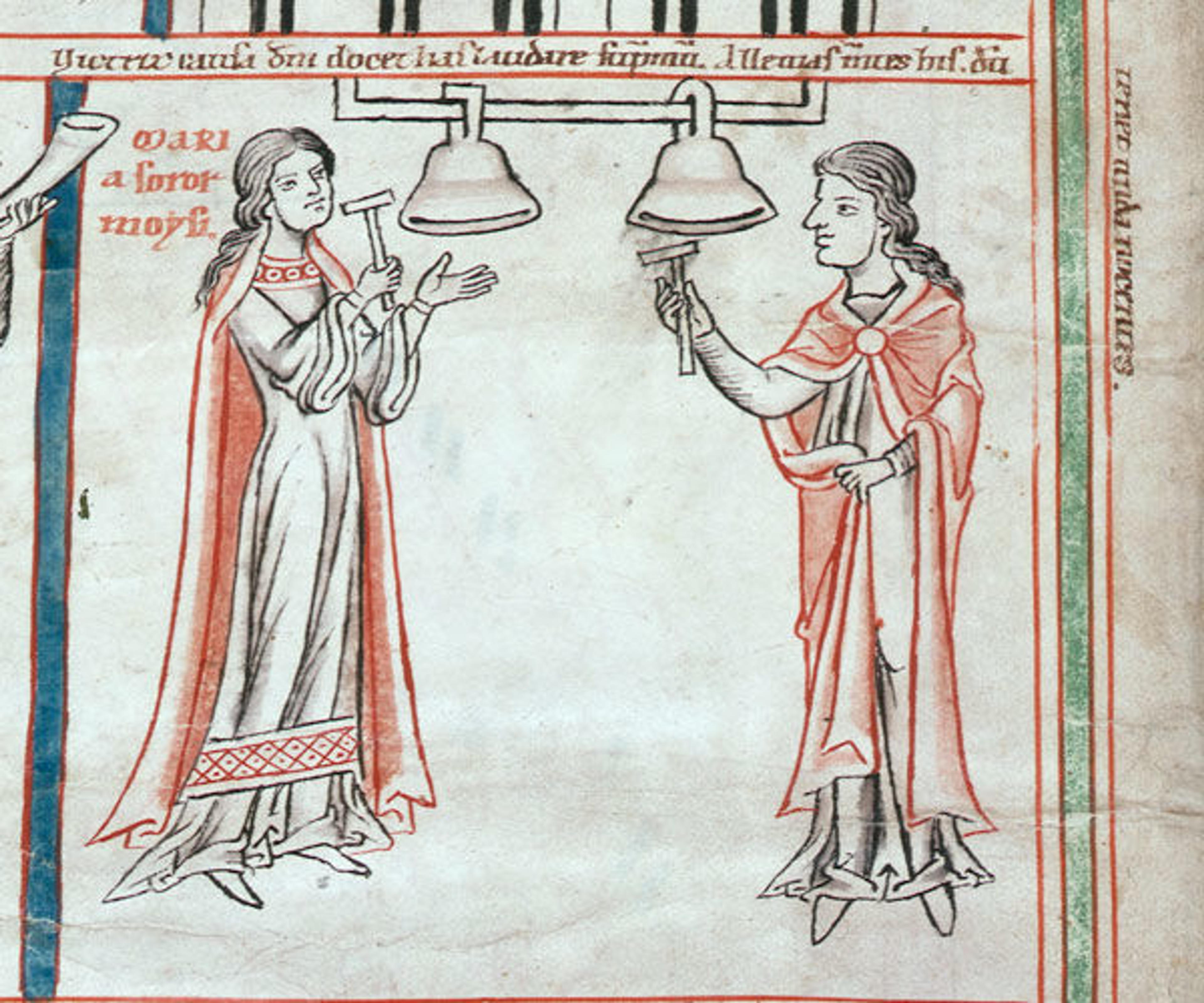

The bell's shape is unusual, but it can be seen in a mid-thirteenth-century manuscript that features illustrations depicting bell ringing and other music making activities. Like the two similar bells in the drawing, our new bell has no clapper and is intended to be struck with a hammer, which produces a clear, resonant sound. The German manuscript and a history of ownership in Germany suggest that the bell was produced there in the thirteenth century.

Glossarium Salomonis, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München, Clm 17403, fol. 5v.

Bells played an important role in the strict regulation of the daily routine of a monastery. Large bells were rung to signal the time to rise, to pray, and to attend the so-called chapter meetings for the community. Prayers at fixed times of the day, known as divine office, were a central element of life. A smaller bell, such as our example, was used only for meal times. The sacrist, who was responsible for the care of the church and its furnishings, or sometimes the prior, had the task of calling the members of the community to the refectory, usually with a bell, but sometimes by beating a board.

Many other sounds, too, would have pervaded the medieval cloister. Singing of psalms and other songs would have emanated from church during the scheduled hours of divine office, day and night, and eating was accompanied by reading aloud from sacred texts. In addition to these sounds of the spiritual life of the monastery, sounds such as water in fountains and of livestock and other animals involved with the work of the community would have resonated within the monastery.

Like the long-standing early music concerts regularly hosted at The Cloisters and the installation of Janet Cardiff's Forty Part Motet in 2013, our new bell will serve to evoke the sounds of medieval life for visitors to the museum.

Peter Barnet

Peter Barnet is the senior curator in the Department of Medieval Art and The Cloisters.