Unlocking the Mysteries of Two Jan van Eyck Frames, Part Two: Imaging the Hidden Details

Jan van Eyck (Netherlandish, ca. 1390–1441) and Workshop Assistant. The Crucifixion; The Last Judgment, ca. 1440–41. Oil on canvas, transferred from wood, each: 22 1/4 x 7 2/3 in. (56.5 x 19.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1933 (33.92ab)

From Maryan Ainsworth, curator in the Department of European Paintings:

In a blog article published last week, I introduced readers to the extraordinary discovery my colleagues and I made of a hidden fragmentary text on the frames surrounding the Crucifixion and Last Judgment by Jan van Eyck and his workshop—a revelation that left us with more questions than answers. What could this text be and when was it added to the frames? Could it have been part of the original concept by the most renowned fifteenth-century Netherlandish painter, Jan van Eyck?

Clearly, we needed the help of a conservator, a scientist, and a paleographer to begin to unravel the mysteries of this unanticipated find. First things first: As Silvia A. Centeno and Sophie Scully discuss in this article, various technical examinations needed to be undertaken in order to determine whether the text was original to the paintings.

Although X-radiographs revealed the existence of a hidden inscription on the frames of Jan van Eyck's Crucifixion and Last Judgment, we wanted to get even more information, so we turned to a newer analytical technique: elemental mapping by X-ray fluorescence, also called macro-XRF. This is a non-invasive imaging method that allows us to map the presence of elements in a painting (or in this case, the frames). While X-rays register all the heavy elements at once, macro-XRF allows us to obtain the distribution of each discrete element—both heavy and lighter ones—such the lead used in the inscription found on the Van Eyck frames.

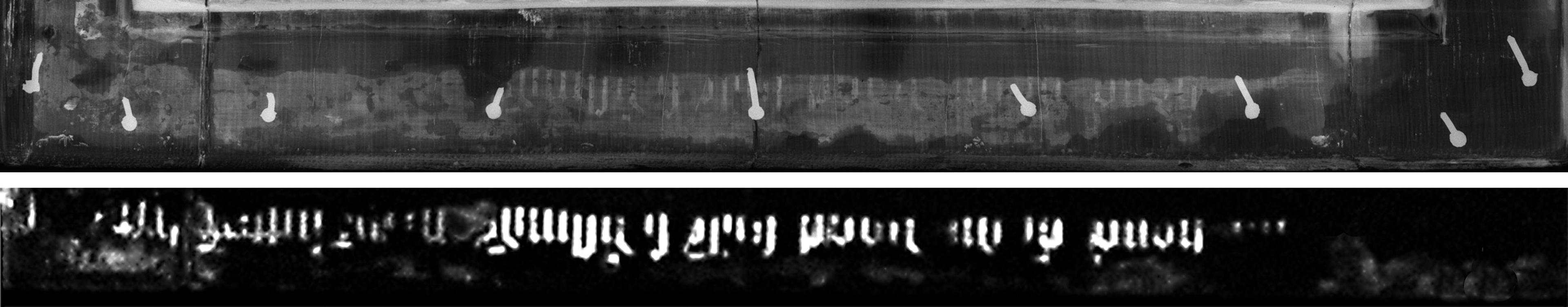

As you can see below, the letters are only faintly visible in the left part of the X-radiograph (top), but in the XRF map that shows the distribution of lead (bottom), you can see that the inscription runs the length of the frame. In fact, we discovered that the inscriptions run around the circumference of both frames.

Detail of the X-radiograph of the Last Judgment frame (top) and a detail of the lead-distribution map acquired by macro-XRF in the Last Judgment frame (bottom)

Each new finding seemed to generate more and more questions. Were these inscriptions original, made at the same time as the paintings? If so, what did they look like and what colors were used? Were the Latin pastiglia letters original, too? Were both inscriptions visible at the same time? And finally, what on earth did they say? For this last question, we turned to paleographer Marc Smith, an expert in deciphering arcane writing (stay tuned for his insights in a future article), but to begin to answer the questions of materials and originality, we decided that it was necessary to take microscopic samples from the frames.

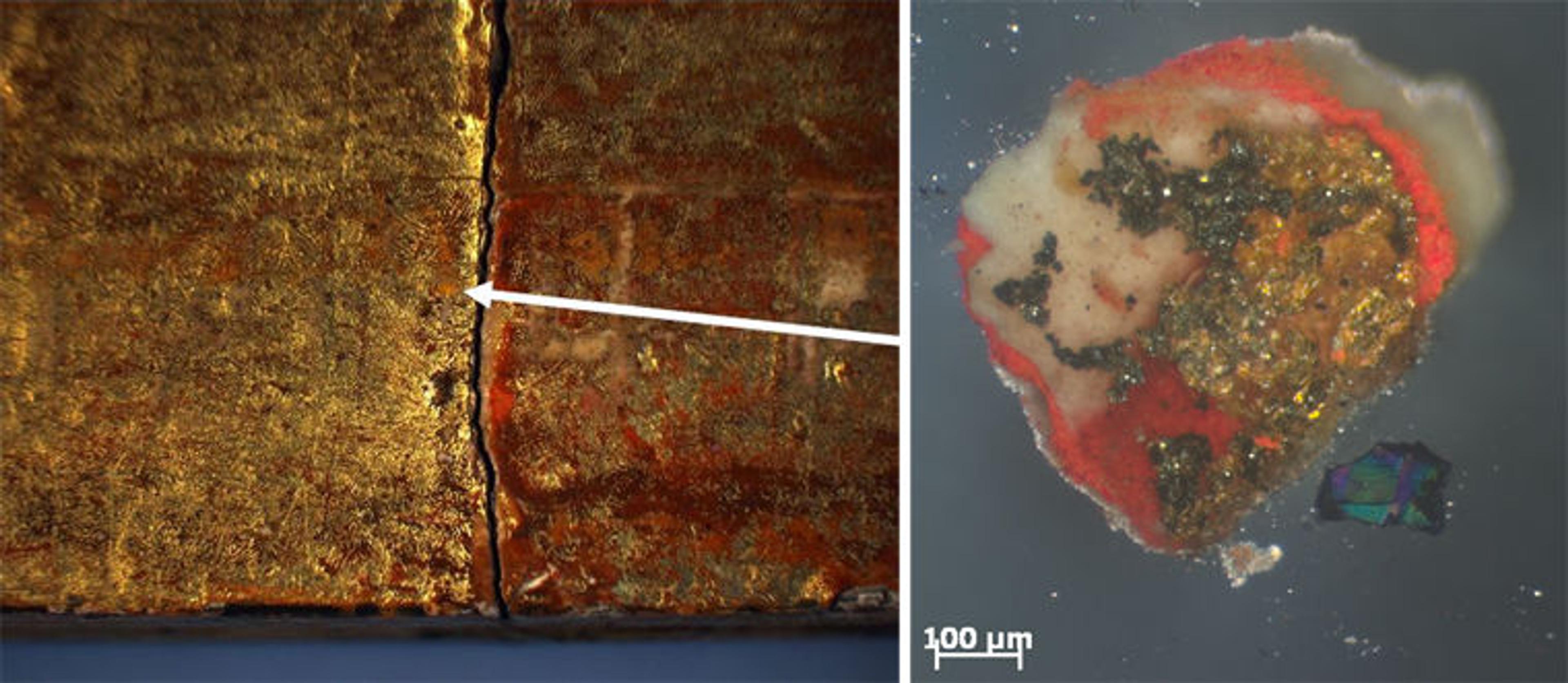

We removed these samples, roughly the size of the head of a sewing pin, from both the inner cove and the flat outer part of the frame. We then mounted these samples in a synthetic transparent resin and polished them (in other words, sanded through using a very fine cloth) so that all the layers in the stratigraphy could be examined in cross-section. These cross-sections revealed that the hidden inscriptions were, in fact, the lowermost layer, buried by many layers of overpaint and re-gilding over the centuries, including the most recent layer of brass leaf. Amazingly, the inscriptions were originally painted in white on top of a bright red paint layer. What we had mistook for a red bole (the clay traditionally used in preparation for gilding) beneath the lowermost gold layer was actually original red paint!

Left: Detail of the Last Judgment frame; the location where the sample was removed from is indicated by a white arrow. Right: The sample before mounting (photographed using polarized reflected light with a 200x magnification)

Sample cross-section showing from the bottom to the top: white ground preparation, red paint layer, colorless layer, part of a white letter, and then several layers of later gilding and repainting (photographed using polarized reflected light with a 200x magnification)

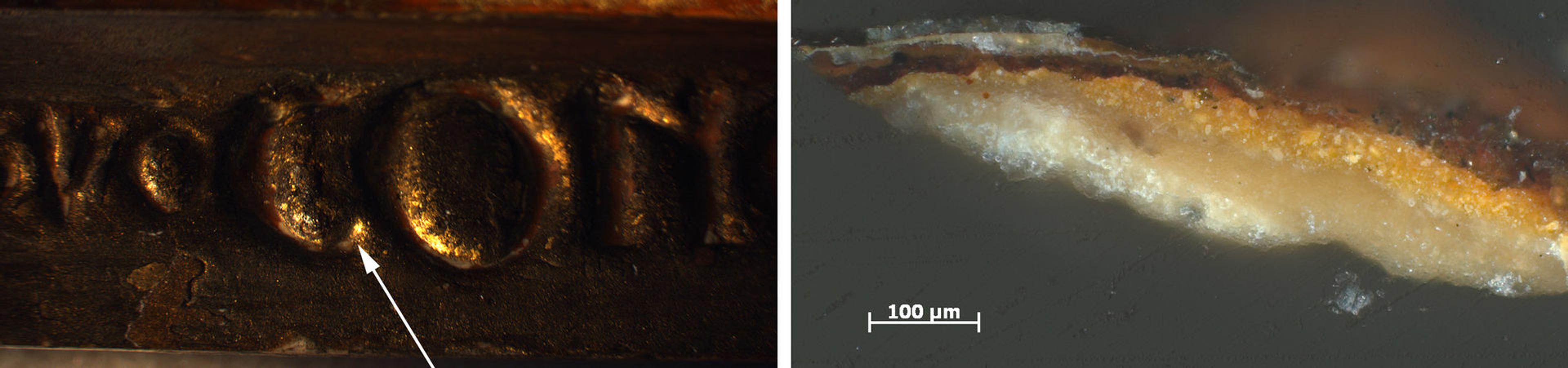

Cross-sections of the pastiglia letters confirmed that the inscriptions were made at the same time as the painting. A layer of apatite—a white material most likely originating from bones and sometimes used to prepare paper for metalpoint drawing—was identified in the preparation of both the pastiglia and the painting using scanning electron microscopy by Federico Caró, research scientist in the Department of Scientific Research. The pastiglia was originally decorated with gold leaf on a yellow mordant, which was consistent with northern European painting practice, but had also been quite damaged and re-gilded several times.

Left: Detail from the Last Judgment frame; the location where the sample from the pastiglia was removed from is indicated by an arrow. Right: Sample cross-section of the pastiglia showing from the bottom to the top: white ground preparation including the layer composed of apatite, yellow mordant layer, gold leaf, and then several layers of later gilding and toning (photographed using polarized reflected light with a 200x magnification)

These imaging techniques and our analyses shed light on the original decoration of the frames, but many questions still remained—the most burning one, of course: What did these frames originally look like? (These tiny samples were only that, tiny samples.) And how would Van Eyck's Crucifixion and Last Judgment look in red-and-gold frames? Check back in next week as Sophie shares the decision to uncover the original inscriptions and the discussion of how best to restore and present these compromised objects to our visitors in the galleries.

The Crucifixion and The Last Judgment are on view at The Met Fifth Avenue in gallery 641.

Related Content

Read a selection of essays on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History that discuss topics related to this article: "Early Netherlandish Painting"; "Jan van Eyck (ca. 1390–1441)"; "Painting in Oil in the Low Countries and Its Spread to Southern Europe."

What's going on in The Met's Old Master galleries? View the web feature Met Masterpieces in a New Light to learn about the European Paintings Skylights Project, in which the skylights that admit natural overhead light into the galleries for optimal viewing of the collection will be replaced, in order to update and improve the quality of light in the galleries and resolve basic maintenance issues.

Silvia Centeno

Silvia A. Centeno is a research scientist in the Department of Scientific Research.

Sophie Scully

Sophie Scully joined the Department of Paintings Conservation in 2012 as a postgraduate intern, going on to be an Annette de la Renta fellow and research scholar before joining the staff in 2017. She works primarily on Old Master paintings with a focus on early Northern paintings; as part of this work she contributes technical text to the online catalogue of the Early Netherlandish collection. She received her BA in art from Williams College, and an MA in art history and an advanced certificate in conservation from the New York University Institute of Fine Arts in 2013.