Exploring Late Monet with Art Historian Kathryn Calley Galitz

Gallery 819, with works by Claude Monet

«Is there such a thing as "late style"? Does experience afford an artist a particular kind of wisdom or insight? History is full of stories of painters cut down in their prime—Egon Schiele died at twenty-eight, Théodore Géricault was only thirty-three—but what about those like Claude Monet (1840–1926), who lived long into old age, and who continued to expand his sensibility? His early pictures of the French seaside resort town of Sainte-Adresse from the 1860s have a muted naturalism that dissolved into almost pure abstraction by the 1920s, when he was painting at his property in Giverny.»

What explains his gradual evolution? I spoke with art historian Kathryn Galley Galitz, a specialist on late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century French art and the author of Masterpiece Paintings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, about Monet's development, his friendships with others, and why Mark Rothko helps us see Monet's art more fully.

Pac Pobric: Part of what's so fascinating about Monet is how long he lived. By the time he died, the world had changed radically since the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874.

Kathy Galitz: Yes, Monet had an extraordinarily long career. He started painting in the late 1850s and continued until his death in 1926. And he's not static, he's not stagnant. That's the sign of a great artist, one who is constantly evolving and responding to what's going on around him. By the time he did his magisterial late water lilies, which are in the Musée de l'Orangerie in Paris, World War I was over, Cubism had happened, and abstraction had emerged. When you look at those late water lily paintings, you can absolutely sense a current of abstraction.

Pac Pobric: Is there a point at which late Monet begins? Is there some scholarly consensus? Or is there something you think defines late Monet?

Kathy Galitz: It depends. I'm thinking about Paul Tucker, who's the great Monet scholar of our lifetimes. He did a show called Monet in the '90s at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The 1890s were when Monet painted his series paintings, sixteen years after the first Impressionist exhibition. Monet was still evolving. Then Tucker did a show called Monet in the 20th Century, which could also be late Monet. Again, it depends on how you look at it. I don't know if there is a specific moment when Monet suddenly became late Monet, but I would say the interests he pursued in the twentieth century started in the later 1880s, when he began thinking in terms of series.

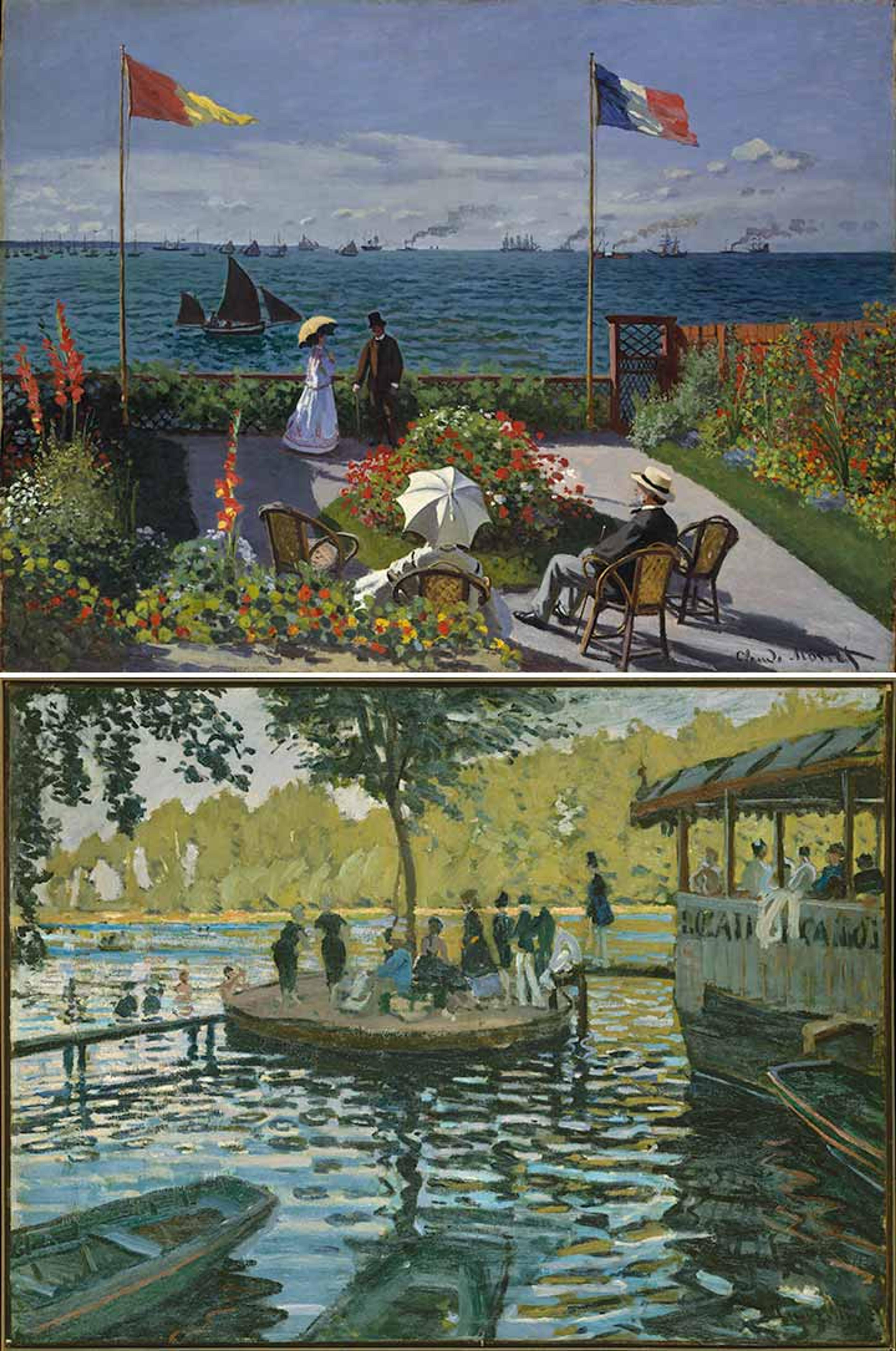

Top: Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). Garden at Sainte-Adresse, 1869. Oil on canvas, 38 5/8 x 51 1/8 in. (98.1 x 129.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, special contributions and funds given or bequeathed by friends of the Museum, 1967 (67.241). Bottom: Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). La Grenouillère, 1867. Oil on canvas, 29 3/8 x 39 1/4 in. (74.6 x 99.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.112)

Pac Pobric: So how does he get there? Where is he early in his career?

Kathy Galitz: Let's look at Garden at Sainte-Adresse from 1867. This was painted on the Normandy Coast, where Monet's family lived. At the time, he was still a struggling artist. He had a pregnant girlfriend in Paris and he was spending the summer with his aunt, who had money, and his father. And in this painting from 1867, you see the seeds of Impressionism in his interest in capturing figures out-of-doors. He's painting plein air light effects; it's a fleeting moment and you get a sense of where the sun fell at this particular moment on a late summer's day. This is where the wind was blowing to animate the flags, that was how it moved the smoke on the ships along the horizon. So it's all there and you get a sense of how his brushwork is evolving, especially when you look at the treatment of the flowers and the figures in the foreground versus the more static, conventional treatment of the water.

Then you look at a painting from two years later, La Grenouillère, which means "frog pond." It was a popular leisure site on the banks of the Seine just outside Paris. Monet and Renoir went there in the summer of 1869, set up their easels, and painted side-by-side. Monet wrote to the artist Frédéric Bazille that summer that all he'd been able to do were some bad sketches. La Grenouillère is one of those "bad" sketches—and it's now seen as an icon of Impressionism.

This is where we see a change in his art. When he made this, he saw this as a step along the way to a finished painting—but not as a finished painting. Yet within less than a decade, he exhibited one of these "bad" sketches in the second Impressionist exhibition in 1876. So his perception of his own work had radically altered. You look at the difference in the water from Garden at Sainte-Adresse to La Grenouillère and you can really see the emergence of that broken brushstroke that's synonymous with Impressionism. La Grenouillère is about the fleeting moment recorded ostensibly in a single sitting. But that's not really the case. We've done technical analysis of this painting, and Monet worked on it on at least four separate occasions. If he allowed a day's drying time between paint applications, that's about a week. So even though it looks rapidly executed, it's a little deceiving. But you can look at areas where he's painting wet-on-wet, where he's not allowing a layer to dry, and the colors bleed. With this stroke of white atop the blue, the white picks up the blue and he's painting wet-on-wet to convey rapidity.

Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). Garden at Sainte-Adresse (detail). Right: Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). La Grenouillère (detail)

Pac Pobric: Who is he talking with at this point in this career? What kinds of conversations is he having?

Kathy Galitz: He is just beginning to make a name for himself at this point. He has exhibited at the Salon in Paris, the official public art exhibition, which really made or broke an artist. It's really a monopoly, and part of the reason the Impressionists had their first show in 1874 is that they kept getting rejected by the Salon. The jury was very mercurial; sometimes you're in, sometimes you're out. So the Impressionists formed their own exhibition group in part to have autonomy and not to be subject to the whims of the Academic painters who were controlling the Salon jury. So who was Monet talking to? He was hanging out with Renoir and Bazille and they were experimenting with painting in the forest of Fontainebleau en plein air. Monet was known by this point, and he probably also knew Manet too, because Manet had made his name earlier, in the 1860s, taking on the establishment at the Salon of 1863 with his Luncheon on the Grass, which was rejected by the jury and shown at the infamous Salon des Refusés. Manet was a kind of icon to these young avant-garde artists because they saw him challenging standards.

Pac Pobric: But Manet was more conservative than they were.

Kathy Galitz: Yes, he wanted to change things from within, even though he didn't always get into the Salon.

Pac Pobric: What happens with Monet's work once he gets to the twentieth century?

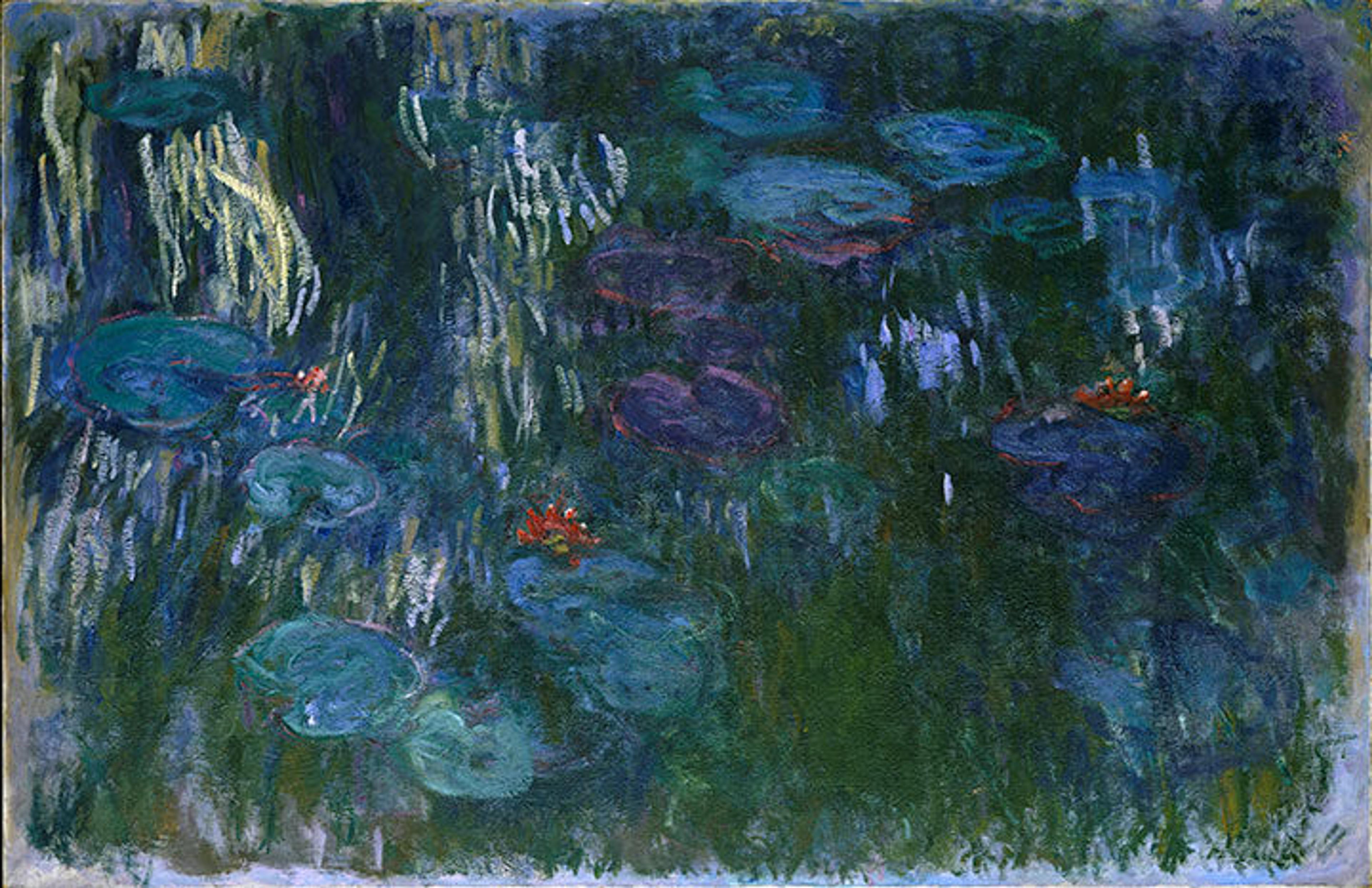

Kathy Galitz: When he made Water Lilies from 1916 to 1919, he was doing studies of the pond at his garden in Giverny for large canvases he would then work on in his studio. So he was not strictly painting outdoors anymore; he was making on-site studies and then reworking them in his studio. We're moving so far beyond the notion of a painting as the capture of a fleeting moment, which was the core idea of Impressionism. This work is the product of sustained observation over a long period of time.

You can even see how different this looks than his earlier Impressionist brushwork. We don't really see that broken brushstroke anymore. The brushwork is larger, broader, freer. We see some of the trees that line the pond reflected in the water, we also sometimes see the clouds. We're looking at the surface of his water lily pond, but we have no horizon line. So we're talking about ideas that are very much twentieth-century ideas—and which verge on abstraction. There's this idea that a painting is no longer simply a record of what is seen.

Pac Pobric: Is there some set of factors that leads him to think about painting in this new way?

Kathy Galitz: I think it's just evolutionary. I don't think there was one moment where he suddenly said, "I've got to do it differently." He was a commercial success. If you look at his series paintings from the 1890s—the Haystacks, Rouen Cathedral, Poplars, Mornings on the Seine—all of the works where he took one motif and painted it under different lighting and atmospheric conditions at different times of day, he was already reworking them in his studio. These were already no longer the record of a particular moment in time, but a product of sustained observation. So he was already seeing differently in the 1890s. Those were hugely successful. If you were an artist like Monet and had a show with a dealer like Paul Durand-Ruel, as he did, and the works sold out as they did, you'd have no financial concerns.

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). Water Lilies, 1916–19. Oil on canvas, 351 1/4 x 79 in. (130.2 x 200.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Louise Reinhardt Smith, 1983 (1983.532)

Pac Pobric: When did those financial concerns begin to disappear?

Kathy Galitz: In 1890 he purchased his home at Giverny, and three years later he bought the adjacent property where he painted the water lilies—which he had imported from Japan, by the way. He invested in the garden and even got permission to redirect a little stream to create a pond over which he built a Japanese footbridge. At this point, he was as much a horticulturalist as he was a painter, and, in his lifetime, he was written-up in gardening magazines. This was not an inexpensive hobby. He hired gardeners to help him maintain the property because it took a lot of work and he was an older man. So that puts it into perspective—he had the financial means to do this.

Pac Pobric: And he had those means for quite some time, because he lived another thirty-six years. That's a healthy lifespan, especially for someone born in 1840.

Kathy Galitz: Yes, and think about everything he experienced. Things have changed a lot in our lifetimes with the internet and the instantaneity with which we can communicate with anyone in the world. But in his world, so much changed too. Photography was invented just before he was born. He saw the railroad, the car, the telegraph, electricity. He experienced so much technological change in his lifetime. And, the Industrial Revolution gave artists a whole range of pigments at their disposal, so that's why the color of a Monet looks so different than an early nineteenth-century Delacroix. So much of what happened in the twentieth century resulted from seeds sown in the nineteenth century.

Pac Pobric: But when it came to the twentieth century, his contemporaries weren't necessarily interested in seeing his newest works.

Kathy Galitz: Well, works like Water Lilies have a strongly abstract quality. Paintings like this languished in Mone's studio after his death and there was no interest in them until the mid-twentieth century, around 1955, the same time as Abstract Expressionism—artists like Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko. Water Lilies was first shown at The Met in 1963. Suddenly these late works took on a whole new resonance. If you think about it, that's why we see Monet at the Museum of Modern Art [MoMA]: That's the modernist side of Monet, and that's how he was perceived in the mid-twentieth century.

J. M. W. Turner is another artist for whom we talk about late works. I curated the Turner show here in 2008 and his interest in light and color at the expense of form in the 1840s made his work increasingly abstract. There really is a late Turner. And in 1966, MoMA did a show focused on late Turner after they'd acquired a color-field painting by Rothko. Just like with Monet, suddenly people saw Turner through a new lens—through the lens of mid-twentieth century abstraction.

Pac Pobric: What happened to some of the other water lily paintings at the time of Monet's death?

Kathy Galitz: Monet was friends with Georges Clemenceau [the Prime Minister of France during World War I] and after the signing of the Armistice in 1918, Monet presented his water lilies to France as a bouquet of flowers. During the war, while he was working in his studio in Giverny, he could hear the trains going to the front. That's pretty powerful.

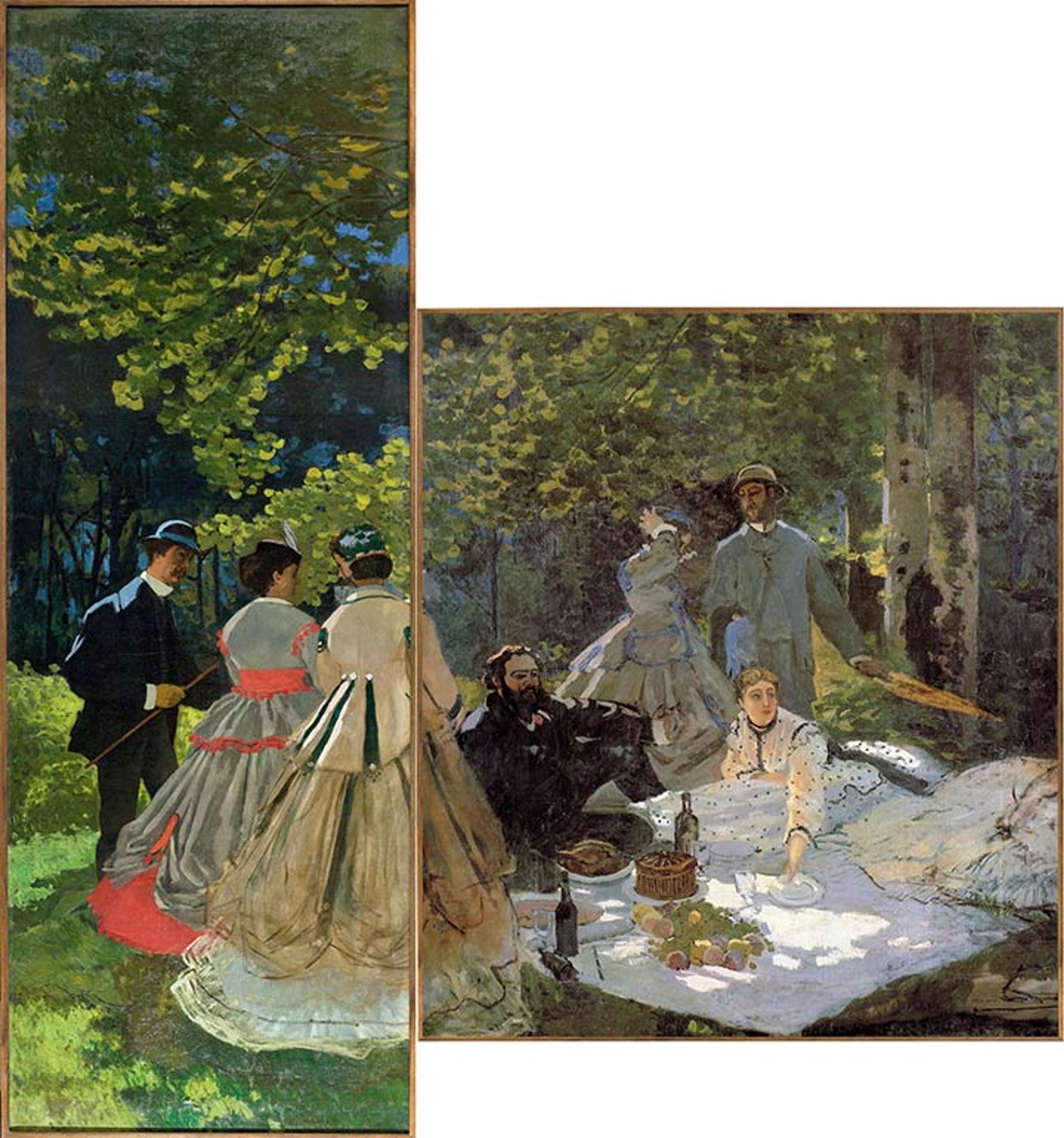

Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). Luncheon on the Grass, 1865–66 (unfinished). Oil on canvas, 97 9/10 x 95 4/5 in. (248.7 x 218 cm). Musée d'Orsay, Paris (RF 1987 12)

Pac Pobric: What about the size of Water Lilies? It's quite big. There is some precedent for Monet working at this scale. I'm thinking of his Luncheon on the Grass from 1865–66 at the Musée d'Orsay.

Kathy Galitz: Yes, he did work large then, but that was when he was trying to take on the Salon and Manet. Manet's Luncheon on the Grass was a succès de scandale in 1863. Monet decided to take on the same subject, but to paint it outdoors rather than in the studio. But he never finished that painting. You can see some of the figures aren't done being painted. He blocked out an area for Bazille's legs—he's the guy sitting on the far right, in a lost section of the picture. You can see the unpainted area in the bottom right corner, where his feet and lower legs would have been. Monet was still a starving artist then, so he just rolled it up and literally left it in a basement. It suffered some damage from moisture and humidity and that's why it exists only in fragments. The only full record of that work is a much smaller sketch at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

Pac Pobric: What about other movements? What is Monet seeing, and is he responding to anything?

Kathy Galitz: He would have seen Pointillism later on because those artists were in the last Impressionist exhibition in 1886. But it was very divisive. Seurat, Signac, and Neo-Impressionism—a lot of the earlier Impressionists wanted nothing to do with it. In fact, the works were exhibited in separate rooms in 1886 because a number of artists said, "I'm not having my painting alongside their painting."

Pac Pobric: So is there a sense that Monet stays on his own track, that he maintains his own sensibility and vision throughout?

Kathy Galitz: Oh yeah, I think so. I think he was charting his own course. Late in life he begins to talk about wanting to capture what he feels, and that notion of feeling—or subjectivity—that's not what he was talking about in the 1860s, when he was painting Garden at Sainte-Adresse or La Grenouillère.

Left: Claude Monet (French, 1840–1926). Rouen Cathedral: The Portal (Sunlight), 1894. Oil on canvas, 39 1/4 x 25 7/8 in. (99.7 x 65.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Theodore M. Davis Collection, Bequest of Theodore M. Davis, 1915 (30.95.250)

Pac Pobric: So those earlier pictures are more scientific?

Kathy Galitz: More objective. I wouldn't go so far as to say scientific. Objective, yes. But this element of subjectivity is something that enters into his art later. It isn't there initially and it wouldn't have been. He had formal artistic training in the Academy, and that's not what they were talking about. Back then, it was radical to paint outdoors and to have a finished painting made outdoors. To paint a scene from modern life instead of a history painting, that was radical. Even landscapes—which were at the bottom of the hierarchy of genres as they had been defined by the French Academy since the seventeenth century—were radical.

Pac Pobric: That's very different from how we see Monet today.

Kathy Galitz: Tastes change. After 1950 or so, we could see Monet through the lens of Jackson Pollock, whereas when Monet painted his late works, there was no Pollock. It changes your perception. How we see art is inevitably colored by the moment in which we live and what we're seeing around us. That's also why scholarship is evolving. You can always rethink things.

View all of Claude Monet's works in The Met collection. For more on the artist, see our Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History essays on Claude Monet, Impressionism, and Post-Impressionism.

Pac Pobric

Pac Pobric is an editor in the Digital Department.