Mary Cassatt in a Modernist Light: A Close Look at Mother and Child

Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926). Mother and Child, 1914. Pastel on wove paper mounted on canvas, 26 5/8 x 22 1/2 in. (67.6 x 57.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.50)

«The American portrait and figure artist Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) is best known for imagery drawn from the private sphere of women—sedate moments in the daily lives of privileged individuals as they read, take tea, attend the opera, or care for their young children. But she was also one of the most inventive practitioners of Impressionism in many media, and not least in pastel, a newly popular medium in the late nineteenth century.» In Mother and Child (1914), currently on view at The Met in gallery 769, we can see that her goal was not only to render a particular type of subject matter, but also to experiment with avant-garde techniques.

Sennelier pastels, ca. 1900. Department of Paper Conservation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Jeanine Humphrey through the Pastel Society of America, 2014

As a professional artist, Cassatt was first introduced to pastel on the cusp of its rebirth in the 1870s. Largely disparaged as a serious medium for almost a century, and relegated to small academic color studies and studies for personal use, pastel regained popularity in the late nineteenth century among the Independents, the predecessors of the Impressionists, whom Cassatt joined at the invitation of Edgar Degas in 1877.

Cassatt excelled in her handling of these simple sticks of powdered color, as exemplified in Mother and Child, a theme she specialized in after 1900. For Cassatt, the medium's modernist appeal rested on several aesthetic factors closely tied to its material properties. Among these properties were speed of execution, a vast array of ready-made colors, and ready adaptability to draftsmanly and broad painterly handling.

As a dry medium, pastel was an ideal means to express the Impressionists' new emphasis on spontaneity; as an opaque medium, its distinctive reflectance responded to the era's fascination with the scintillating effects of natural light. The unvarnished matte surface of these works also implied a truthfulness or directness that was in opposition to the fiercely rigid academic establishment.

As a modernist, Cassatt was attracted to pastel as a vehicle for new ideas on color, light, and spontaneity. Her forceful colorism exemplified the theories of Michel Eugene Chevreul and Ogden Rood, which formed the chromatic basis of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.[1] Their primary message was that when hues opposite each other on the color wheel are layered or placed adjacent to one another, they are intensified in richness.

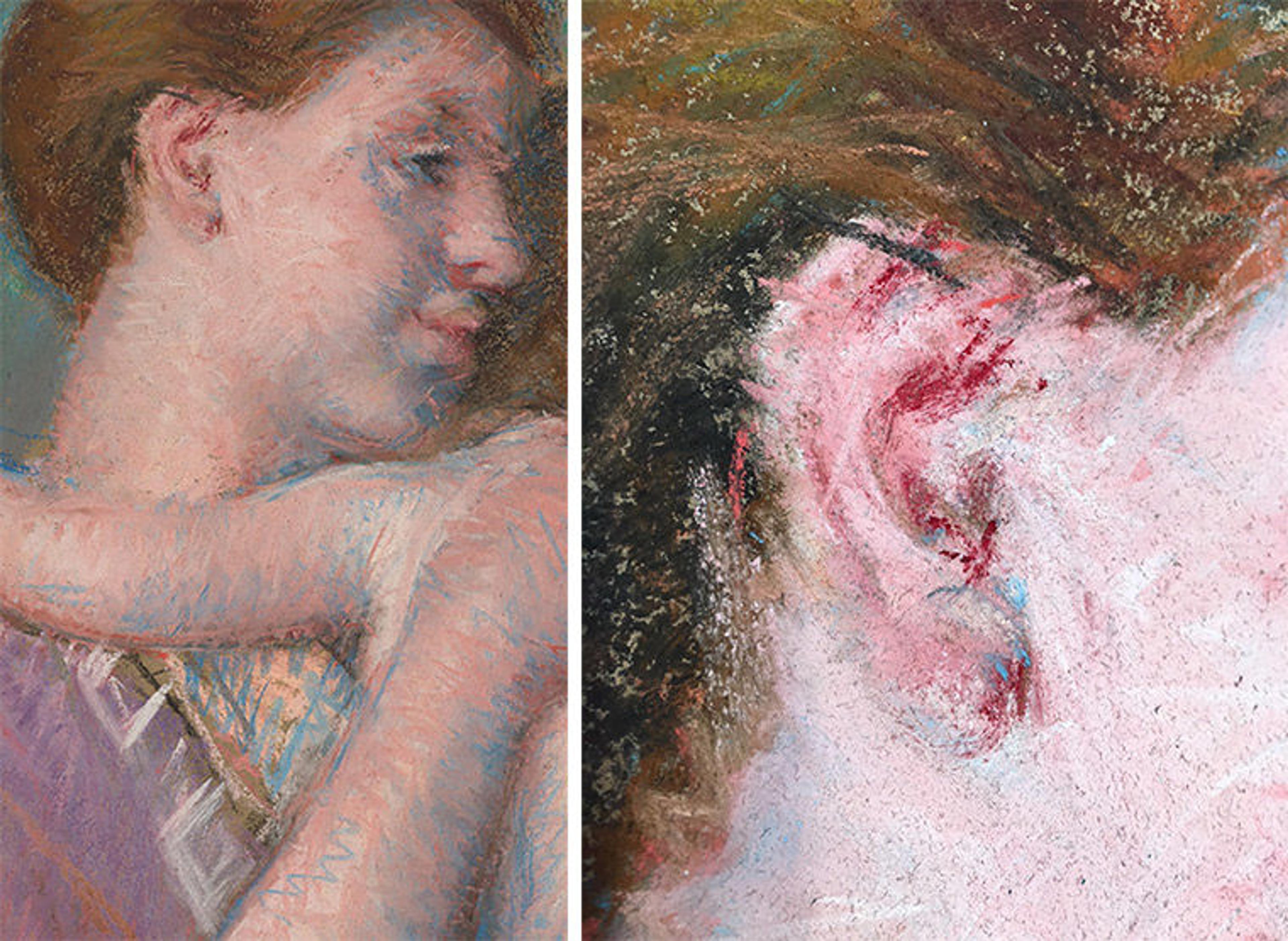

Mother and Child (detail), 1914

This orchestration of complementary colors is unmistakable in Mother and Child in the clashing of the luminous pink flesh tones, the violet dress, and the vibrant green background, as well as in the blue undertones of the skin. The latter—so evocative of the Italian Primitives, who were active from the late thirteenth to the fifteenth century and revered by the Impressionists—was an effect the press had criticized in Cassatt's work many years before as looking "dirty" and in need of washing.[2]

Cassatt's boldness in her later years in continuing to embrace a new visual language to depict modern life is expressed in the daring of her execution: the summary yet precise charcoal underdrawing visible through the colored layers (above), as well as in the spontaneity conveyed by her radical draftsmanly mode of applying broken, unblended, and overlapping strokes.

Mother and Child (details), 1914

This facture, which is evident both in the broad passages of fleshtones and in the blue, white, and red hatches and zigzags that accent and define these robust figures (above), created new opportunities to juxtapose color. The lack of finish in the mother's face, which is consistent with the rendering of the dress, imparts a quality of abstraction not generally present in her work, far unlike the naturalistic detail she characteristically produced by blending and stumping (below).

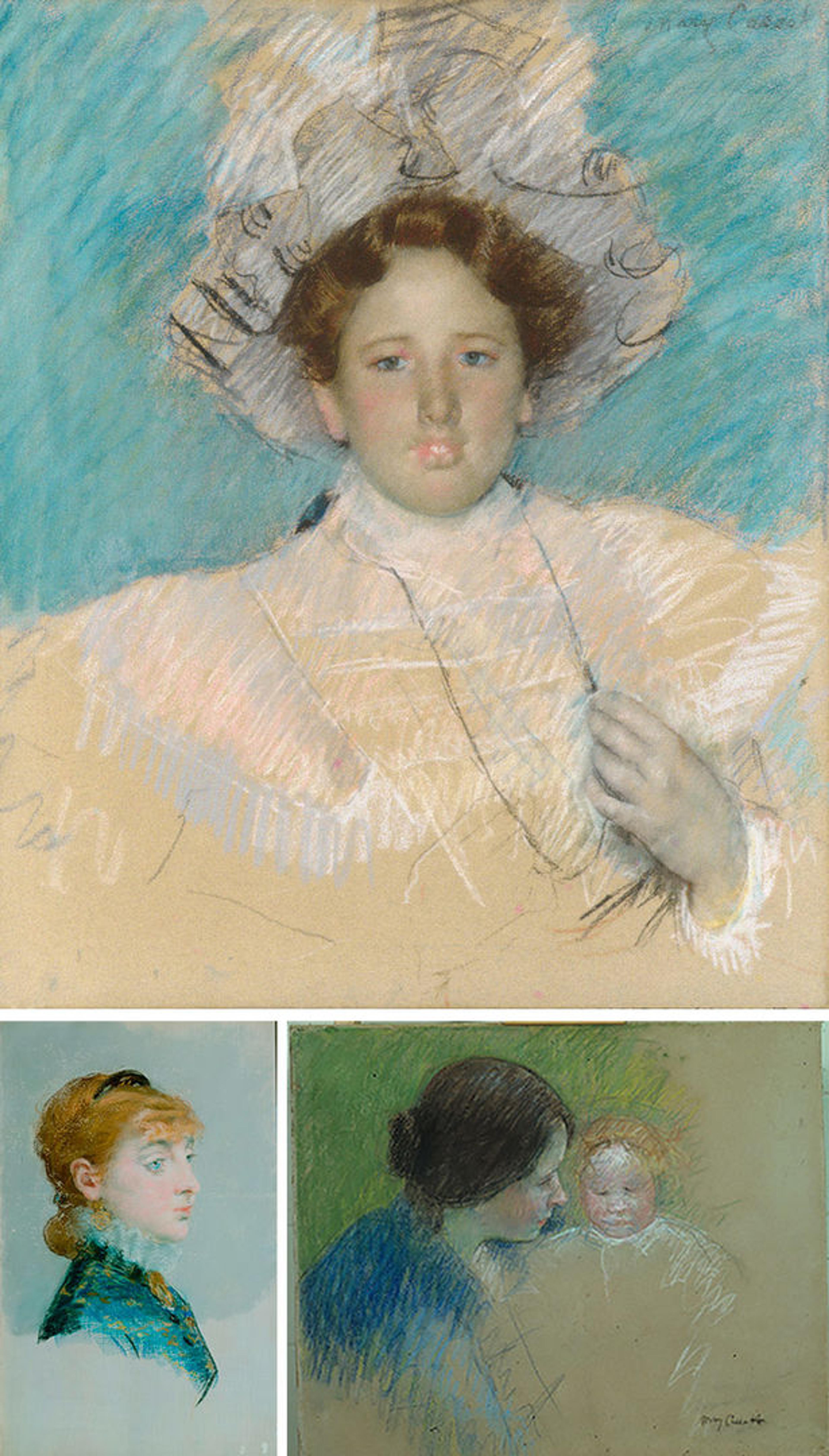

Top: Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926). Adaline Havemeyer in a White Hat, probably begun 1898. Pastel on wove paper, mounted on canvas, 25 1/2 x 20 in. (64.8 x 50.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of members of the family of Adaline Havemeyer Frelinghuysen, 1992 (1992.235). Bottom left: Édouard Manet (French, 1832–1883). Mademoiselle Lucie Delabigne (1859–1910), Called Valtesse de la Bigne, 1879. Pastel on canvas, 21 3/4 x 14 in. (55.2 x 35.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H. O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H. O. Havemeyer, 1929 (29.100.561). Bottom right: Mary Cassatt (American, 1844–1926). Mother and Child, 1906. Pastel on paper, 21 1/2 x 25 3/4 in. (54.6 x 65.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Mrs. Gardner Cassatt, 1958 (58.191.1)

Cassatt, more than many of her contemporaries, had a sophisticated grasp of the modernist technique of leaving areas of the composition unfinished to express a draftsmanly spontaneity. Based on the concept of the nonfini (the "unfinished"), this device was also a frequent practice of Édouard Manet, one of her mentors (above, bottom left).

The technique of contrasting the "reserves" (or exposed areas of the paper) with dense passages of color is present in a great many of her pastels. We find it in the large central areas left untouched in Adaline Havemeyer in a White Hat (above, top) andinMother and Child(1906) (above, bottom right).

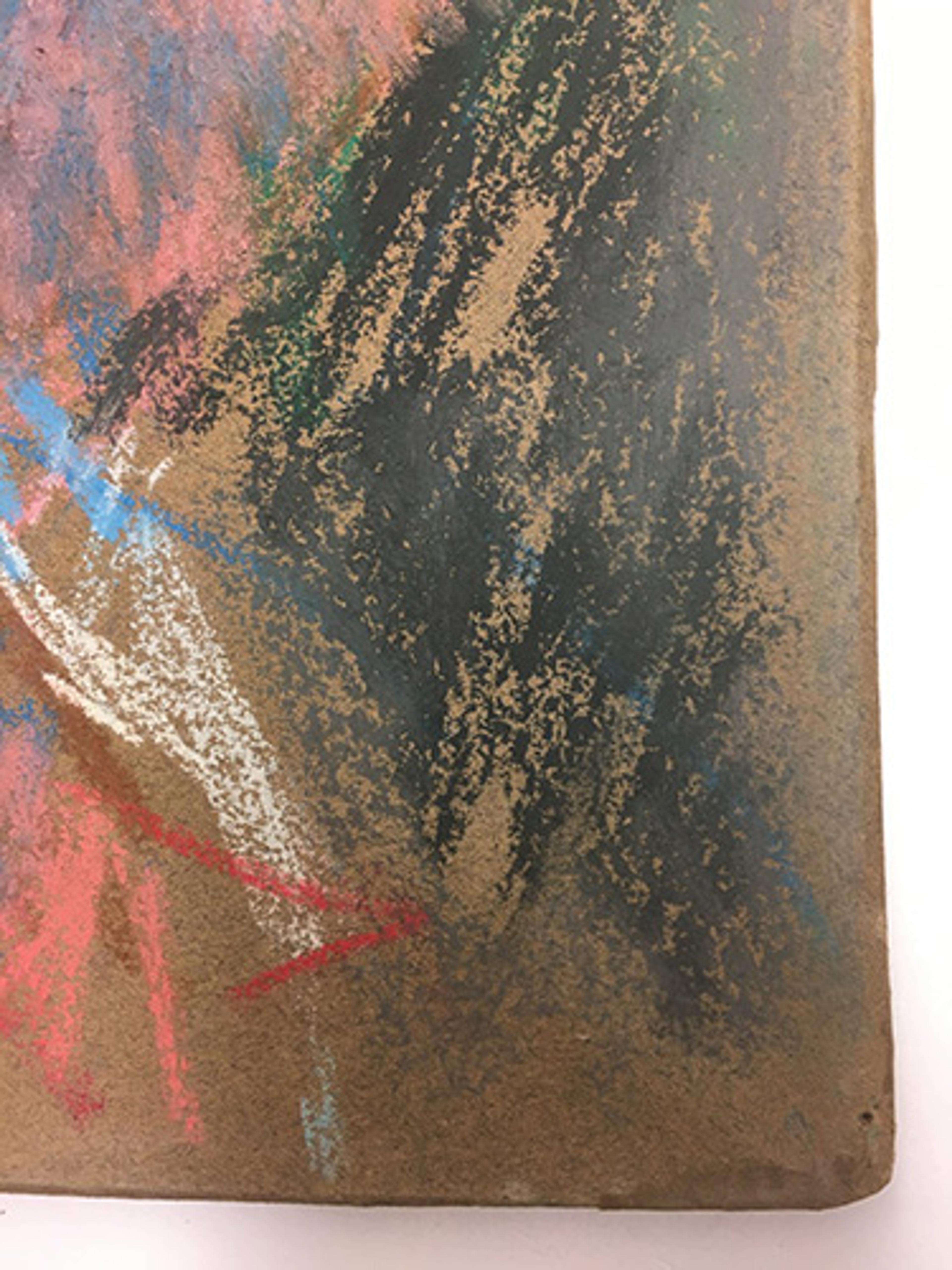

Left: Lower right-hand corner of Cassatt's Mother and Child, 1914

In Mother and Child (1914), it can be seen at the corners of the sheet (left), as well as in the many gaps between the broad strokes of color in the hair and at the perimeter of the forms.

Unlike traditional pastel practices, in which all traces of the paper were obscured by pigment, these reserves were intended to reveal the colored sheet below.

Cassatt's preference was for blue paper, as in Mother and Child, but paper in many hues had been available for several decades and was widely employed by nineteenth-century pastelists. Such supports were comparable in function to the toned grounds of canvases used by the Impressionists, in which the hue provided a chromatic element that played against loosely painted strokes. These colored papers inevitably faded to a warm brown (above) as a consequence of the unstable synthetic aniline dyes (the first coal-tar colors) used in their manufacture, a tonal alteration not intended by the artist.

But the most modernist feature of the Havemeyer composition is Cassatt's experimentation with imparting luminosity. The Impressionists were committed to increasing the effect of light in their work, and pastel's appeal lay in its special optical qualities: both the scattered light reflected from its innumerable particles at a micro level, and the light reflected from the irregular surface of the composition itself. The uneven amount of pastel deposited with each stroke produces a textural roughness that amplifies light. This impasto-like quality, which was antithetical to the varnished surfaces of Salon art, evoked the primitivism of fresco, gouache, and tempera that was greatly admired by the avant-garde artists of the day.

Cassatt capitalized on this distinctive property of pastel in Mother and Child not only in her dense and irregular application of the medium, but also in her daring manipulation of the powdery texture in the flesh tones of the two figures and in the immediately surrounding green background. Unlike the direct flat strokes that she used for the hair and dress, the pastel here appears grainy when viewed in oblique or "raking" light. This unusual texture does not, however, result from a conventional dry application of the medium or from sticks of pastel dipped in water; instead, it is an effect she achieved by experimenting with steam.

Cassatt may have been inspired by a technique that her frequent collaborator, Edgar Degas, used to fix pastel. But she did something different. Degas, following a secret recipe provided by the artist Luigi Chialiva, boiled his solution and blew the steam onto localized areas of his composition.[3] This effect can be seen in the flatness and slight luster in the hair of many of his female subjects. Like Degas, Cassatt selectively exposed Mother and Child to moisture vapor. But unlike him, she then seems to have sifted crushed pastel onto the treated surface, so that its slight dampness agglomerated the particles into minute clusters as it dried.

Left: Flesh tones from Cassatt's Mother and Child, 1914. Right: Conservators' recreation of Cassatt's texture using the method described above

The details of her process are not recorded, but here in the Department of Paper Conservation at The Met our attempts to recreate her special texture (above left) using this method yielded plausible results (above right), whereas directly wetting the sticks of color, or combining pastel dust with water, resulted in a thick, paint-like medium.

But the method itself was not as important to Cassatt as the way the technique enabled her to amplify light. Degas used moisture to stabilize pastel in localized areas so that he could overlap strokes without muddying their chromatic intensity. Cassatt's aim in altering the surface in Mother and Child was different. The absence of clues such as a visibly compact or glossy surface or analytical evidence of a fixative suggests that unlike Degas she was not using this treatment to create a barrier layer or to consolidate the powdery medium. Her goal was to increase the irregularities in the surface as a way to enhance the amount of reflected light.

To maximize this effect she focused her procedure on the highest-keyed colors in the composition, which included the brilliant pink flesh tones and the green background, which has been heightened in luminosity with strokes of pale gray pastel. Beyond this point, the background shifts to darker gray and green, and the granulation ceases. Given the extremely brittle surface that this technique produced, and the fact that no similarly worked pastels by Cassatt have yet been identified, this may have been a one-off experiment.

In striking contrast to her impressive repertoire of avant-garde techniques, Cassatt was one of the few Impressionists who regularly employed an eighteenth-century mounting format, comparable to that used for oil paintings, for her works in pastel.

Most artists were by now executing their pastels on paper mounted on millboard (a thick, rigid cardboard made from hemp ropes and recycled paper). The paper was mounted to the board either by adhering it along the edges or by wrapping and pasting the margins to the back of the panel. This modern format allowed for a resilient working surface and fit easily into a frame.

Left: The back of one of Mary Cassatt's pastels, mounted on an eighteenth-century-style strainer. Right: The back of another Cassatt pastel, showing the paper attached to canvas on a strainer

Cassatt, on the other hand, typically executed her pastels on paper that was adhered to canvas and tacked to a wood strainer (a stretcher with fixed dimensions) (above right). This is the format she used for Mother and Child. Commercially prepared and available in a range of sizes, this more costly structure offered no particular advantages over the millboard mount and, once framed, its more highly finished effect could only be appreciated from the back (above left).[4]

Cassatt's reason for choosing this traditional format is not known. She or her dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, may have thought it would appeal to conservative patrons by tempering the unfamiliarity of these modernist works. Or it may have been a personal statement of this strong-willed, innovative artist that testified to her firm grounding in academic practices and the belief she applied to both her technique and her subject matter: "To be a great painter, you must be classic as well as modern."[5]

Notes

[1] Michel Eugene Chevreul, De la loi du contraste simultané des couleurs, et de l'assortiment des objets colorés, considéré d'apres cette loi (Paris: Chez Pitois-Levrault et Ce.), 1839; and Ogdon Rood, Modern Chromatics (London: C. K. Paul), 1879.

[2] "Symptoms of Revolution: Art in Paris," The New York Times (April 27, 1879): 2.

[3] Denis Rouart, Degas in Search of His Technique (Geneva, Switzerland: Skira; New York: Rizzoli), 1988; transl. of Degas à la recherche de sa technique, 1945; and Adelyn D. Breeskin, Mary Cassatt, Pastels and Color Prints (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press), 1978.

[4] At some point in the mid-twentieth century, the Cassatt pastel was removed from its strainer to counteract tears at the corners.

[5] Louisine W. Havemeyer, "Mary Cassatt," Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum 22.113 (May 1927): 381.

Marjorie Shelley

Marjorie Shelley is the Sherman Fairchild Conservator in Charge of the Department of Paper Conservation.