Brass Beginnings: A Fanfare for the Conch Trumpet

Installation view of Fanfare in gallery 680

«It is easy to imagine the sense of awe, power, and potential felt by the first person who unwittingly summoned sound from a conch by blowing into its broken-off tip. This scenario is central to William Golding's classic coming-of-age novel, The Lord of the Flies: a group of schoolboys have just survived a plane crash that has stranded them on a deserted tropical island, where they are left to their own devices to survive. Something emerging from the sand captures the character Piggy's eye. He exclaims to his friend Ralph: "It's a shell! I seen one like that before. On someone's back wall. A conch he called it. He used to blow it and then his mum would come. It's ever so valuable." The boys quickly grasp the practical and symbolic power of the conch trumpet: "We can use this to call the others. Have a meeting. They'll come when they hear us . . . Him with the shell . . . Let him be chief with the trumpet-thing."»

The sound of the conch gave its player a powerful, superhuman voice and the ability to communicate. Humble but majestic, at once both practical and mystical, the trumpet formed by the conch's elegantly spiraled helix became a medium for signaling, conveying power, spiritual practice, and music making. This status grants it pride of place in the center of The Met's Fanfare gallery, which chronicles the use and design of brass instruments across time and place.

The first "brass" instrument (the vernacular Western term for any wind instrument sounded by buzzing the lips into it, regardless of the material used to make it) was certainly a found object, and a conch shell with its tip broken off is a likely candidate since it required no further modification to make it sound. Other contenders include hollow bones and animal horns, but the physical properties of the conch gave it particularly strong musical potential. Its gently expanding interior spiral forms an ideally proportioned windway for producing a strong, clear tone.

Different sizes of conches offer different pitch possibilities. Larger conches with their longer spiral are lower and can produce more than one note. Players can also alter the pitch of the notes by inserting their fingers and hand into the shell's opening. An illustration in the Codex Magliabecchi depicts an Aztec quiquizoani with his hand in the shell, suggesting that this phenomenon was known to conch players of the mid-sixteenth century. Not until two hundred years later did European natural-horn players start to use a similar hand technique to produce more notes on the natural horn.

The geographic and chronological span of conch playing is immense. Among the earliest surviving conch trumpets are those that were used in the Mediterranean region, some of which date to the Neolithic period, between 6000 B.C. and 3000 B.C. The instrument, made from a variety of native species, was known across Europe, in India, China, Japan, Tibet, Oceania, and the Americas, but seems to have been largely absent in northern Africa. It is noteworthy evidence of their importance and distribution through trade that conches were also used in inland areas far from the sea. The conch continues to be played in many of these places today, such as the Melanesian example from the late nineteenth century below.

Conch shell trumpet, late 19th century. Vanuatu. Melanesian. Conch shell, 12 x 6 in. (30.5 x 15.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.772)

Although it has always served as a very effective signaling device and was often used as a war trumpet, the conch achieved exalted status as a sacred instrument in ritual and religion around the world, including Hinduism, Buddhism, and the spiritual practices of Mesoamerica. It is often associated with the controlling of natural elements related to its habitat—such as rain, water, and wind—and with fertility. The conch is also used to represent the sacred breath of life. All of these attributes made the conch trumpet an emblem of status in the secular realm as well, where conches and items fashioned from them were popular objects in Kunstkammer collections.

The rate of expansion of the spirals of conchs and nautilus shells often exhibit the mathematical proportions of the golden ratio, also known as the golden mean. This placed them in both the celestial and terrestrial world through the Classical concept of the music of the spheres and through mousike, which embraced not only music and drama, but also math, science, and philosophy. The golden ratio was often expressed in the design of musical instruments. Early forms of the horn as depicted in the 1500s and 1600s, for example, resembled conches and snails in the way their tubing was formed and coiled. The ratio was also employed in the proportions of violins and other stringed instruments.

These powerful and intriguing intersections of sound, science, spirituality, and the natural world continue to be expressed in the enduring popularity of conch trumpets. Explore their many forms, uses, and exulted status below in examples from The Met collection, as well as two loaned works on view at The Met through May 28 in the landmark exhibition Golden Kingdoms: Luxury and Legacy in the Ancient Americas.

This sacred Maya conch on display in the Golden Kingdoms exhibition produces a sound that would have been considered the thunderous music of the ancestor. Conch trumpet, A.D. 250–400. Guatemala, Northeastern Petén. Maya. Shell, cinnabar, 11 9/16 x 5 1/4 in. (29.3 x 13.4 cm). Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas (AP 1984.11)

This ancient spoon from Peru—also on view in Golden Kingdoms—was possibly used to inhale hallucinogens during religious ceremonies, and features a figure playing a conch-shell trumpet. Bimetallic effigy spoon, 400–200 B.C. Peru, Chavín de Huántar. Chavín. Gold, silver, H. 4 3/8 x W. 1 x D. 1 7/16 in. (11.1 x 2.6 x 3.6 cm). Pre-Columbian Collection, Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. (PC.B.440)

The conch trumpet is a sacred instrument of Hinduism. Śankh, 19th century. Kerala State, India. Shell (Turbinella pyrum), brass, wax, 6 x 6 x 16 3/4 in. (15.2 x 15.2 x 42.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Barrington Foundation Inc. Gift, 1986 (1986.12)

The god Vishnu is often depicted holding his usual attributes, which include a conch trumpet. Vishnu, 10th–11th century. India (Punjab). Sandstone, H. 43 1/2 in. (110.5 cm), W. 25 5/8 in. (65.1 cm), D. 10 in. (25.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1968 (68.46)

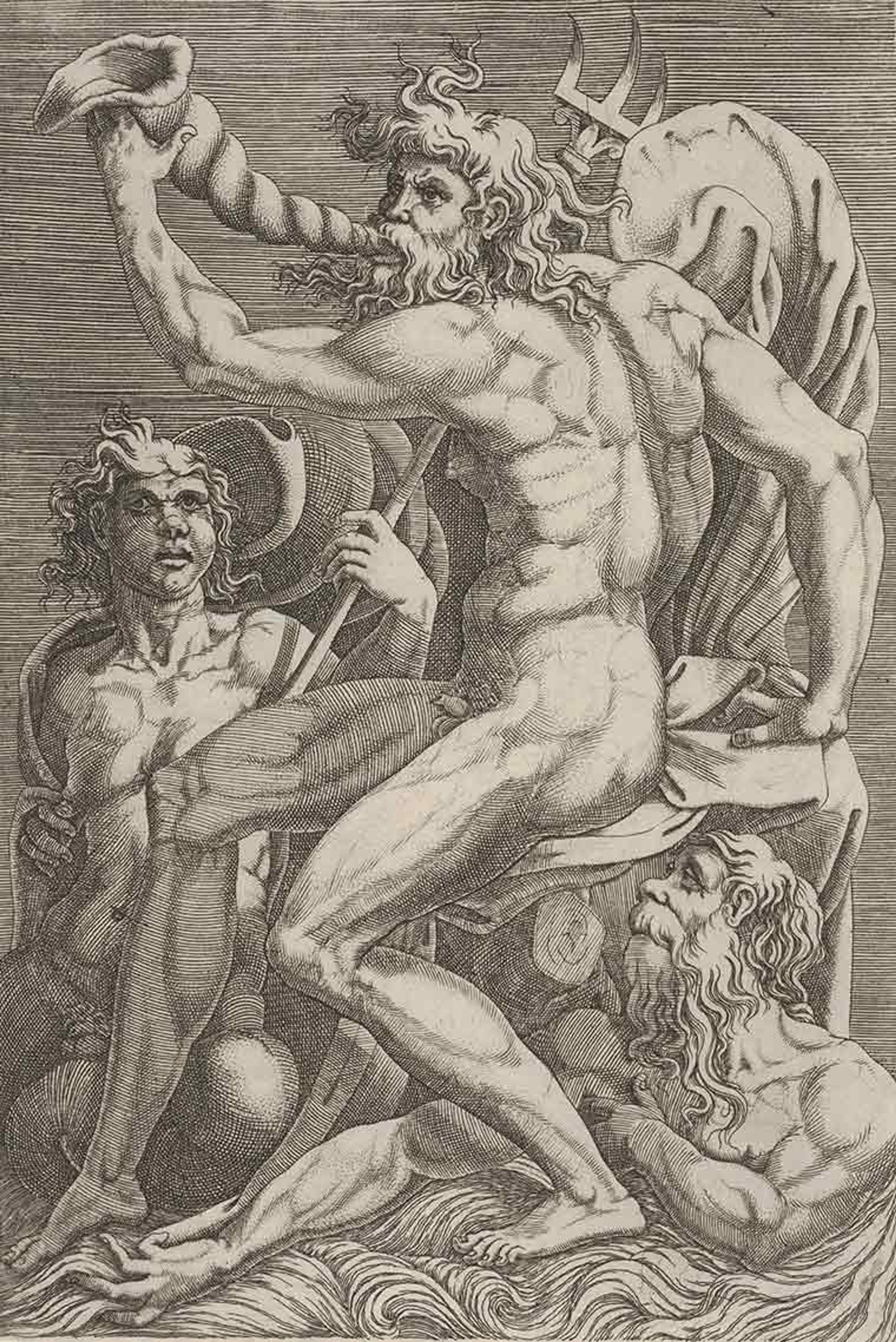

In Roman mythology the conch trumpet was an attribute of Neptune and the Tritons, who sounded it to control the winds. Attributed to Giorgio Ghisi (Italian, ca. 1520–1582) after Perino del Vaga (Pietro Buonaccorsi) (Italian, 1501–1547). Seated Neptune Holding a Conch Shell to His Mouth, Accompanied by a Seated Triton and Another Emerging from the Water at Bottom Right. Engraving, sheet: 9 1/8 x 6 1/8 in. (23.2 x 15.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Phyllis Massar, 2011 (2012.136.80)

The conch trumpet was an auspicious and noble instrument in China during the Ming dynasty. Nardunbu (Manchu, active mid-17th century). Horsemanship Competition for the Shunzhi Emperor (清 那爾敦布 順治皇帝進京之隊伍賽馬全圖 卷) (detail), dated 1662. Chinese, Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Handscroll; ink and color on paper, 8 x 655 in. (20.3 x 1663.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Dillon Fund Gift, 2002 (2002.328)

The horagai was played in Japan as a war trumpet and is also sounded by practitioners of Shugendō. Horagai or rappakai, 19th century. Japan. Shell; triton, tritonis, H: 38.1 cm (15 in.); W: 15.2 cm ( 6 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.93)

The form of this helmet is inspired by the hora, a Japanese conch trumpet that was used in battle. Helmet in the shape of a sea conch, 17th century. Japanese. Iron, gold, silver, H. 12 in. (30.5 cm), W. 12 3/4 in. (32.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Collection of Giovanni P. Morosini, presented by his daughter Giulia, 1932 (32.75.243)

Bradley Strauchen-Scherer

Dr. Bradley Strauchen-Scherer is an associate curator in the Department of Musical Instruments.