Furniture plaque carved in relief with a winged female figure and a “sacred tree”

Not on view

During the early first millennium B.C., ivory carving was one of the major luxury arts that flourished throughout the ancient Near East. Elephant tusks were carved into small decorative objects such as cosmetic boxes and plaques used to adorn wooden furniture. Gold foil, paint, and semiprecious stone and glass inlay embellishments enlivened these magnificent works of art. Based on certain stylistic, formal, and technical characteristics also visible in other media, scholars have distinguished several coherent style groups of ivory carving that belong to different regional traditions including Assyrian, Phoenician, North Syrian and South Syrian (the latter also known as Intermediate).

Several ivories in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection are from the Aramaean town of Arslan Tash, ancient Hadatu, in northern Syria just east of the Euphrates River, close to the modern Turkish border. French archaeological excavations at the site in 1928 revealed city walls and gates in addition to a palace and temple that were built when the Neo-Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III (744-721 B.C.) turned the town into a provincial capital and military outpost. During the excavations, over one hundred ivory furniture inlays that can be attributed to the South Syrian and Phoenician styles were found in a building near the palace. One piece bears a dedicatory inscription in Aramaic to King Hazael, mentioned in the Bible, who ruled Damascus during the second half of the 9th century (ca. 843-806 B.C.), suggesting that this collection of ivory furniture inlays could have been taken by the Assyrian state as tribute or booty from Damascus. The Arslan Tash ivories share an amalgamation of Egyptianizing motifs typical of the Phoenician style and forms characteristic of North Syrian art that may indicate a South Syrian or Damascene origin of this group. Today, these ivories are housed in museums in Paris, Aleppo, Jerusalem, Karlsruhe, and Hamburg, as well as The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

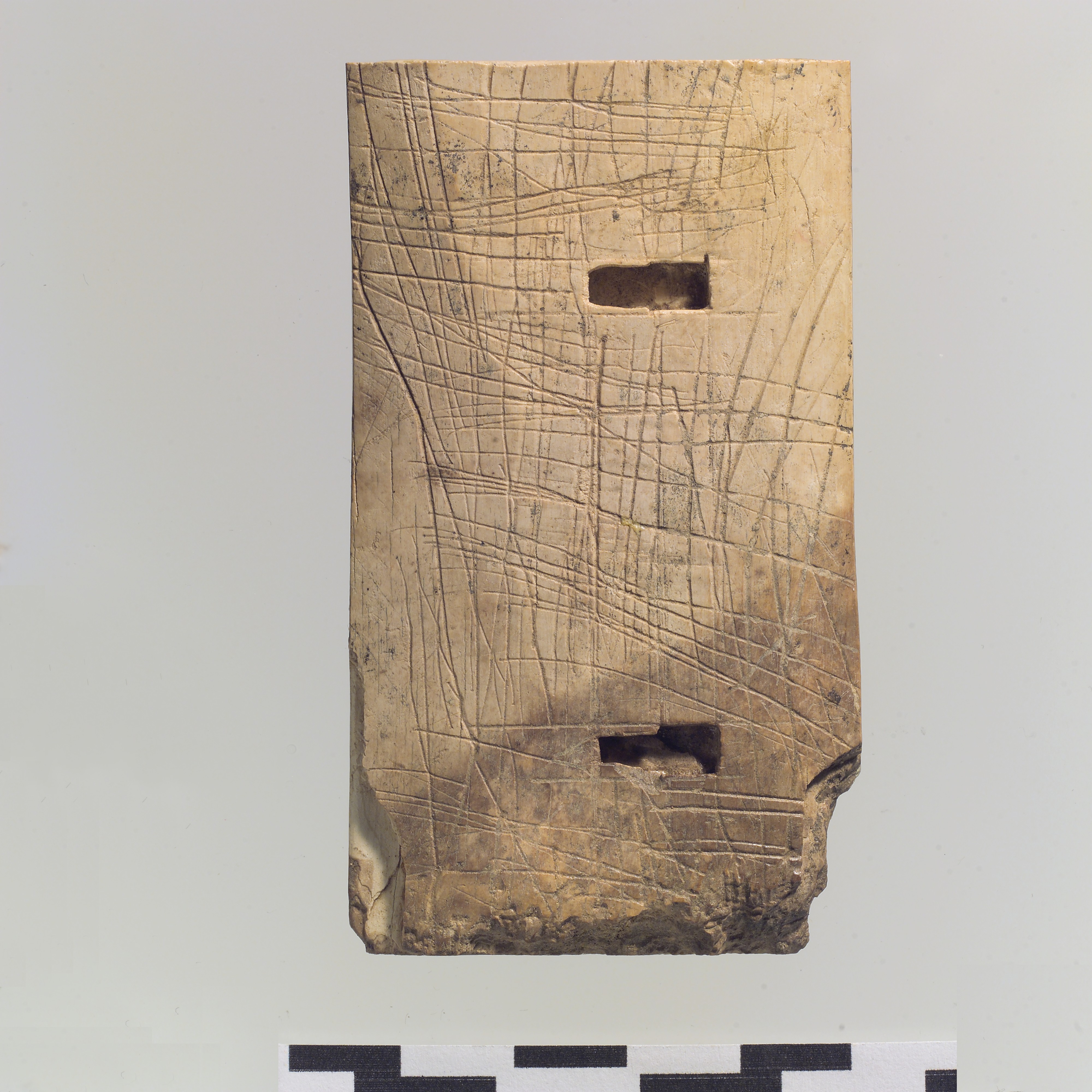

This fragmentary plaque is carved in low relief and depicts a standing, winged female figure set within a thin frame, facing a tree with lotus and palmette elements. One arm and wing are raised while the other arm and wing are lowered; she holds lotus buds in each hand. Attributed to the South Syrian style, this plaque combines elements of both Phoenician and North Syrian artistry. Drawn from the Phoenician tradition are Egyptianizing forms such as the pschent crown (the double crown of Upper and Lower Egypt), the long wig, the floral forms of the tree, and the composition of the female’s body: face and feet in profile with a frontal chest. Features of the North Syrian style include the long, plain, fringed robe, large eyes and ears, and rounded nose. Gold foil is preserved on the upper wing and on the palmette and lotus tree branches. Two mortises cut into the roughened back of the plaque suggest that it was likely made to receive pegs for insertion into a piece of furniture. The complete inlay may have depicted another identical female facing this one, flanking the tree in a symmetrical composition characteristic of Phoenician art. While the king or winged deities of Mesopotamian derivation flank the “sacred tree” on Assyrian reliefs, here the images are drawn from Egyptian art.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.