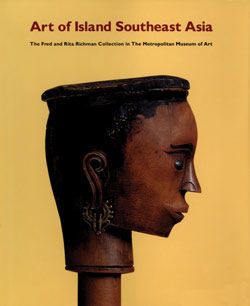

Perminangken (container for magical substances)

The tripartite composition of the carved wooden stopper on this container presents a variation on the equestrian theme. An avian creature combining aspects of the chicken and the hornbill is shown perched on the head of a figure mounted on a horse whose head is that of the mythical singa, a serpent-like creature that figures prominently in Toba Batak art. The entire cosmos—with upper and lower worlds united by the middle world of the living—is represented in the combination of the three elements of this composition: bird, human, and singa. Birds in Batak mythology were often associated with the upper world of the beneficent spirit kingdom, while the serpent was a symbol of the underworld. The symbolic associations of these images, however, were not restricted to a single realm. Birds such as the hornbill and the chicken were also associated with the lower world of the dead. The singa, while identified with the serpent (naga) of the underworld, also warded off evil in the earthly realm. And living human beings of the middle world could make a transition to the other realms through ritual possession or death.

The stopper fits into an imported container with crackled glaze of a type known as Sawankhalok ware, named after the kiln site in Thailand where it was made. It was probably manufactured between the fifteenth and the seventeenth century and demonstrates the widespread use of imported wares from the Asian mainland among the various groups in Island Southeast Asia, including the Toba Batak. The stopper was then locally carved, and the container was used to hold pukpuk, a powerful substance made from ritually prepared human and animal remains. To enliven sacred objects such as ritual staffs and human figures, pukpuk was applied to the surface or inserted into holes in the object that were later plugged, sealing the power within.

The Toba Batak, one of six groups among the Batak peoples of northern Sumatra, live in the mountainous highlands surrounding Lake Toba (the birthplace of the Batak, according to oral histories and myths). The Batak maintained trade relations with their Malay neighbors living on the coast but otherwise remained relatively isolated until the 18th and 19th centuries when Dutch and British traders, along with German missionaries, established operations in Sumatra. Although nearly all Batak today are Christian or Muslim, they formerly recognized diverse supernatural beings, including deities, ancestors, and malevolent spirits. The primary religious figures in Batak society were male ritual specialists, called datu by the Toba Batak, who acted as intermediaries between the human and spiritual worlds. Much of Toba Batak sacred art centered on the creation and adornment of objects that would be used by the datu for divination, curing ceremonies, malevolent magic, and other rituals. Among the most important were ceremonial staffs, books of ritual knowledge, and a variety of containers used to hold magical substances, such as this perminangken.

References

Capistrano-Baker, Florina H. Art of Island Southeast Asia. The Fred and Rita Richman Collection in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994, pp. 53, fig. 23

Sibeth, Achim. The Batak. London: Thames and Hudson, 1991

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.