Annunciation

Workshop of Niccolò Roccatagliata Italian

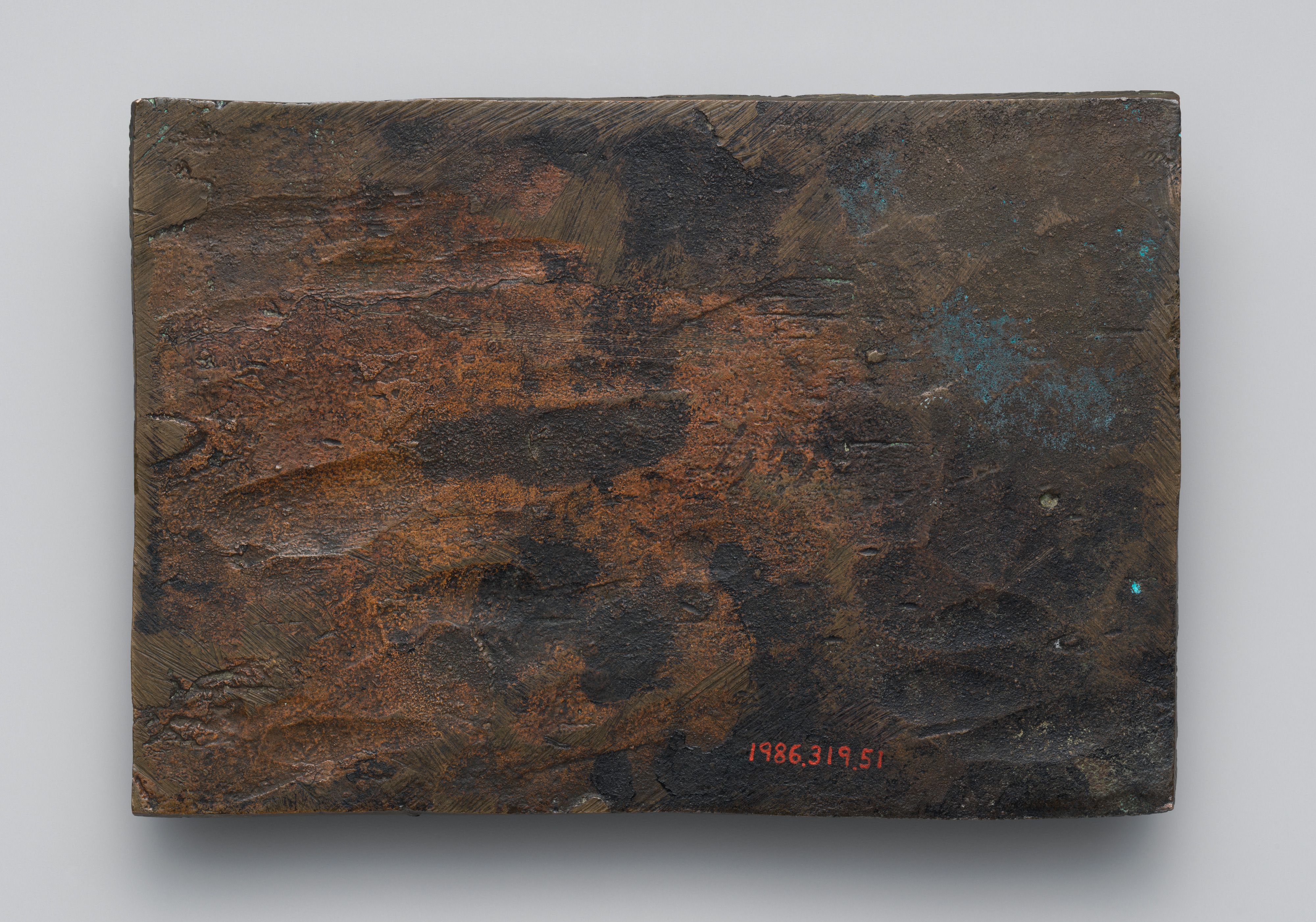

Given its weight (2.3 pounds) and painterly roughness, this bronze Annunciation should not be considered a plaquette, but rather a small relief. Gabriel, accompanied by rays of light, greets the Virgin, who raises her hands in surprise. Between them, a table holding a book and flowers is rendered with an inaccurate perspective, and incense wafts upward. A casting flaw is visible on the Virgin’s cheek. The reverse of the relief is flat.

Charles Avery attributed this work to Nicolò Roccatagliata based on its stylistic similarities to the large, highly ambitious Allegory of the Redemption, a bronze relief in the church of San Moisè, Venice, signed and dated 1633 by the artist and his son Sebastiano Nicolini.[1] A native of Genoa, Roccatagliata likely moved to Venice in the early 1590s.[2] His first biographer, Raffaele Soprani, stated that he made models for Tintoretto.[3] The sense of movement and the vibrant handling of the material in the Annunciation are indeed reminiscent of the late sixteenth-century Venetian painterly tradition. The relief’s surface is characterized by a vivid plasticity. Some of the elements are delineated only by rapid scratches. On the one hand, what James David Draper called the composition’s “dramatic pictorial language” is certainly appealing to the modern eye. On the other hand, the coarse approximation of anatomical proportions (in particular, the excessively large heads and hands) and the clumsy perspective cannot be ignored. Such primitive treatment would be unusual for Roccatagliata, who is among the indisputable masters of Venetian bronze sculpture.

In this respect, the comparison between the Annunciation and Roccatagliata’s relief for San Moisè is problematic. More generally, the Redemption’s style and dating necessitate caution when used as a basis for attributions. Some similarities can indeed be noted between the present Virgin and the female figure in the bottom left corner of the Redemption (fig. 67a). But the latter is a peripheral figure whose quality of execution places her at a remove from the brilliant central scene. In addition, the timeline of the Redemption is complex: the work is dated 1633, when Nicolò had been dead for four years. His son likely hoped to underline the continuity of the family workshop in the Latin signature, in which, exceptionally, the chasers are remembered, namely the Frenchmen Jean Chenet and Marin Feron.[4] Considering all these matters, and that the Redemption involved a collaboration of four sculptors, it does not seem to be solid ground for the ascription of the Annunciation relief to Roccatagliata himself, but possibly to his workshop. Regarding the composition, however, it is worth mentioning a mid-seventeenth-century ivory relief, clearly based on our bronze, albeit in mirror image with minor changes, formerly on the art market, which might indicate the existence of a series.[5]

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. See Planiscig 1921, pp. 621–26. On the activity of both father and son, see also Kryza-Gersch 1998.

2. Siracusano 2017b, who found what is—as far as we know—the first documented work by Roccatagliata in Venice: a silver reliquary for San Giorgio Maggiore executed in 1593, according to Marco Valle’s manuscript De monasterio et abbatia S. Georgii maioris, 1693, fol. 130v.

3. Soprani 1768–69, vol. 1, pp. 353–55.

4. See cat. 66, note 6.

5. Sotheby’s, London, July 5, 1990, lot 240.

Due to rights restrictions, this image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.