The Upside-down Catfish

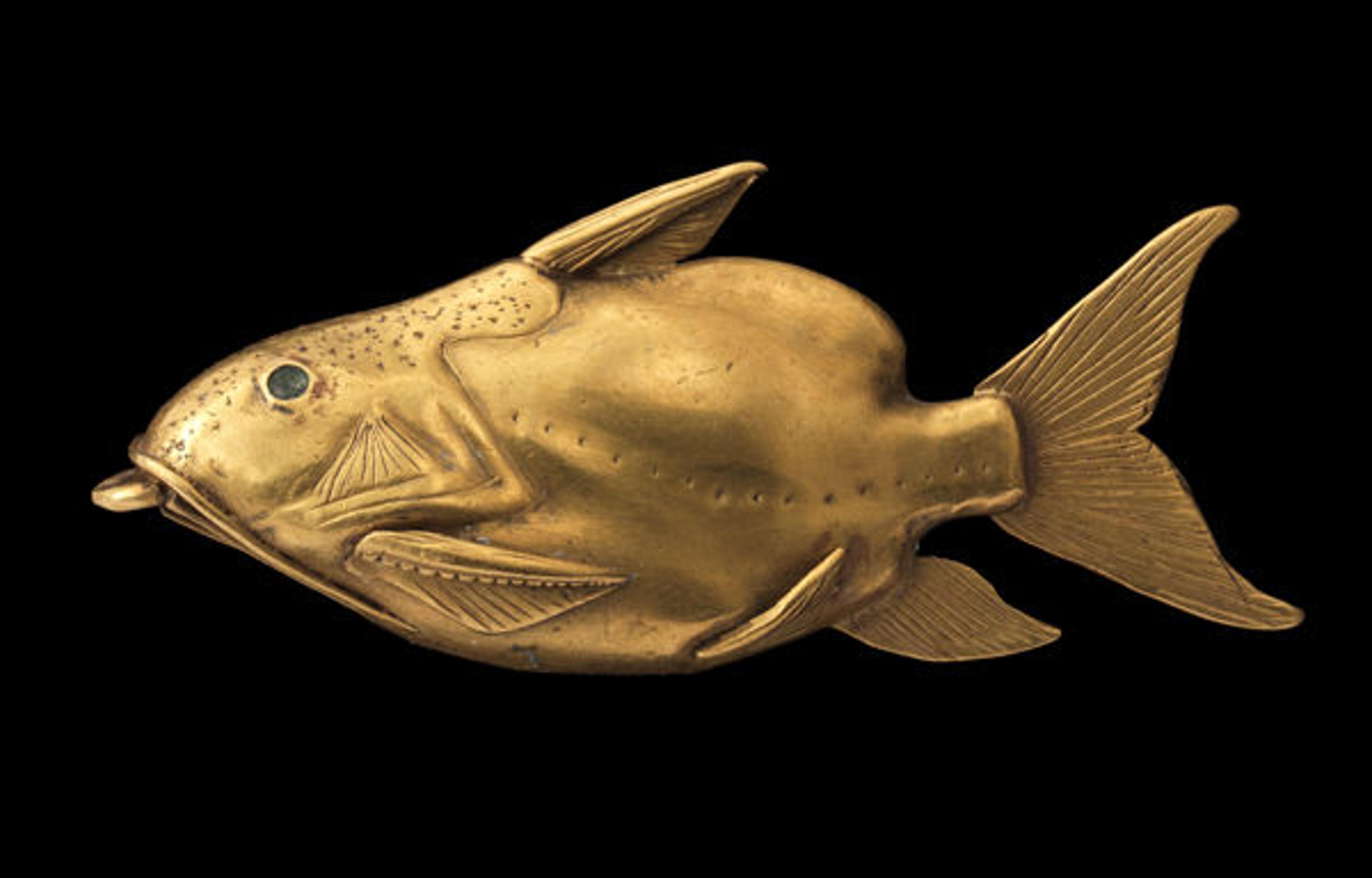

Fish Pendant. Late Dynasty 12–early Dynasty 13 (ca. 1878–1749 B.C.). Gold over a core of unknown material; L. 3.9 cm (1 9/16 in.), H. 1.6 cm (5/8 in.). On loan courtesy of National Museums Scotland (1914.1079)

«Who can resist a piece of exquisite jewelry thought to bear magical properties?

This wonderful fish pendant on loan from the National Museums Scotland is on view through January 24, 2016, in the exhibition Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom. Exemplifying the high craftsmanship of jewelry makers during the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1650 B.C.), this pendant also embodies the magic that was part of life for the ancient Egyptians, which they incorporated into a wide variety of objects.»

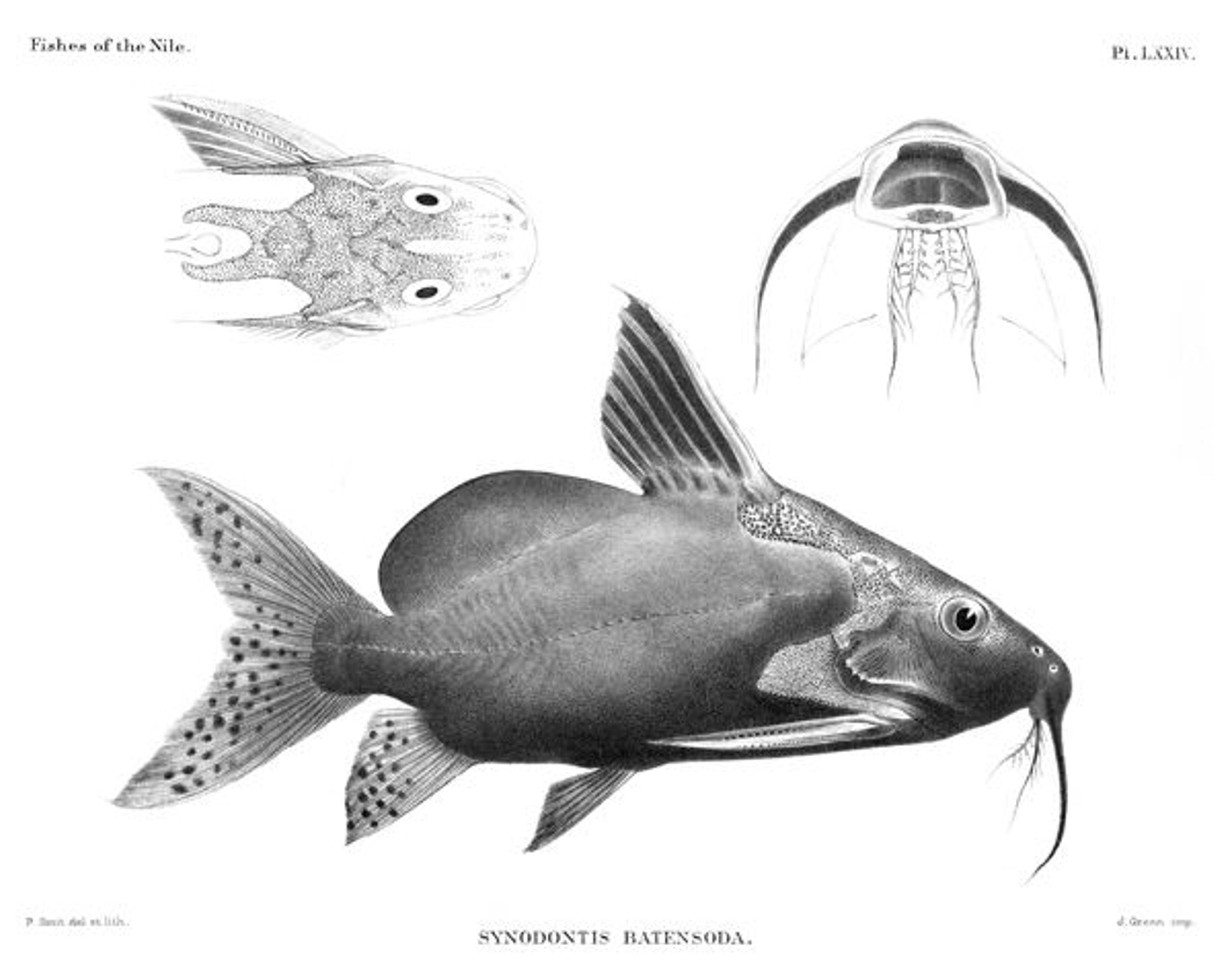

A loop for suspension extends from the mouth of the fish, which would have hung vertically. Despite the fact that it is only one and a half inches (four centimeters) in length, the pendant features amazing details—including the pores that create the so-called lateral line along its sides, the sharp ray on the dorsal fin, the mottling on the head, the comb of small spines on each side between the eye and the triangular gill cover, and the "whiskers" (barbels) that extend from its mouth. The naturalistic depiction of the fish identifies it as a Synodontis batensoda, also known as the "upside-down catfish."

Synodontis batensoda (the "upside-down catfish"). George Albert Boulanger, Zoology of Egypt: The Fishes of the Nile (London: Hugh Rees Limited, 1907), pl. 74.

This type of catfish often swims upside down and very close to the surface. Modern scholars know that ancient Egyptians observed this fish's unusual behavior because of various depictions, as in the Middle Kingdom tomb relief from Lisht below.

A Synodontis batensoda swimming upside down in a detail of a Middle Kingdom tomb relief from Lisht. Dieter Arnold, Middle Kingdom Tomb Architecture at Lisht, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Egyptian Expedition 28 (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008), pl. 124b.

A fish pendant features famously in an ancient Egyptian tale that is part of what we now call the Westcar Papyrus. The story describes how young, beautiful women, wearing only "nets," were rowing a king across a lake when one woman's turquoise fish pendant fell from her braid into the water. She stops rowing, thus disrupting the boat party. Though the king offers her a replacement, the woman refuses; she wants her own pendant returned. The story ends happily when a magician recovers the lost pendant by moving half of the water in the lake onto the other half!

Turquoise Fish Pendant. Late Dynasty 12–early Dynasty 13 (ca. 1878–1749 B.C.). Turquoise, gold; L. 2.1 cm (13/16 in.), H. 1 cm (3/8 in.), Th. 0.4 cm (3/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1909 (09.180.1182)

Depictions also tell us that fish pendants were worn as vertical hair ornaments. A lovely example in the exhibition is a cosmetic container from the British Museum, which is displayed next to the gold fish pendant. It features a kneeling girl with a long braid from which a fish pendant dangles down her back—in this case a different species, probably a tilapia. The girl also wears a girdle with cowrie shells, which are linked to fertility; silver cowries that may have come from such a girdle were also found with the gold fish pendant.

Cosmetic Container with a Girl Wearing a Fish Pendant. Dynasty 12 (ca. 1981–1802 B.C.). Black steatite; H. 7.8 cm (3 1/16 in.), W. 3.3 cm (1 5/16 in.), D. 6 cm (2 3/8 in.). The Trustees of the British Museum, London (AES 2572)

Fish pendants were likewise much more than mere ornaments. They were thought to be imbued with amuletic properties, which is possibly why the young woman from the boat party was so keen to retrieve her own. Usually fish pendants depict either the upside-down catfish or the tilapia. As keen observers of animals, the ancient Egyptians often connected a particular behavior to special powers, and both species can be associated with regeneration. The Synodontis batensoda's peculiar position in the water bears some resemblance to a dead fish floating belly-up on the surface, but on the other hand it was clearly alive. Tilapias, connected to the goddess Hathor, were a symbol for fertility and regeneration since they carry their eggs in their mouths until they hatch.

Amulets were most commonly worn on a necklace, and the use of fish pendants as hair ornaments suggests that the braid of hair itself might be significant. Braids were also associated with the goddess Hathor as well as youth and sexuality, which always implied regeneration and rebirth in ancient Egypt. The Egyptians probably viewed the magical power of the fish pendants in terms of fertility and regeneration, and perhaps connected the wearers themselves to the goddess Hathor.

Besides its use as a magical charm, the gold fish pendant now on view in Ancient Egypt Transformed is undoubtedly a spectacular miniature artwork and the best-surviving pendant of its kind. A direct encounter with art is still something that cannot be reproduced digitally, so seeing it in person here in New York is a wonderful opportunity that you should not miss when you next visit the Met!

Related Links

Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom, on view October 12, 2015–January 24, 2016

Met Blogs: View all blog posts related to this exhibition.

Isabel Stünkel

Isabel Stünkel is an associate curator in the Department of Egyptian Art.