Understanding and Sustaining Cultures: The Conservation of Nepalese Jewelry

Leaf-Shaped Box, 17th–19th century. Top decoration: Newari; box: Tibet, Lhasa area. Gold, diamonds, topaz, emeralds, rubies, sapphire, pearl, aquamarine, lapis lazuli, and turquoise; 6 x 2 1/2 in. (15.2 x 6.3 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1915 (15.95.167)

«I've always been drawn to the role that art and artifacts play in shaping our collective history and culture. As a college intern in the Department of Objects Conservation here at the Met, I recently had the unique opportunity to spend some one-on-one time with beautiful jewelry from Nepal while assisting with the preparation for the exhibition Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas.»

The jewelry on display in this exhibition was made from sheet metal, either gold or gilt silver, and decorated with a variety of precious and semiprecious stones—coral, pearls, turquoise, and lapis lazuli, among other materials. They were used in religious traditions, often adorning images of the gods of Nepal and Tibet. The task of the conservation team was to research the materials and construction of the objects and to carry out treatments that would improve both their aesthetic appearance and structural integrity.

Our analysis began by examining the jewelry under a high-powered microscope, looking for clues as to how the objects were constructed. During observation, we found that the individual stones were set into small cylinders of sheet metal soldered to the object's surface.

Amulet Case with Vishnu Riding Garuda, 17th–19th century. Nepal. Gold, rubies, sapphires, pearls, zircon, coral, lapis lazuli, and turquoise; 2 1/2 x 2 1/4 in. (6.3 x 5.7 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1915 (15.95.173a, b)

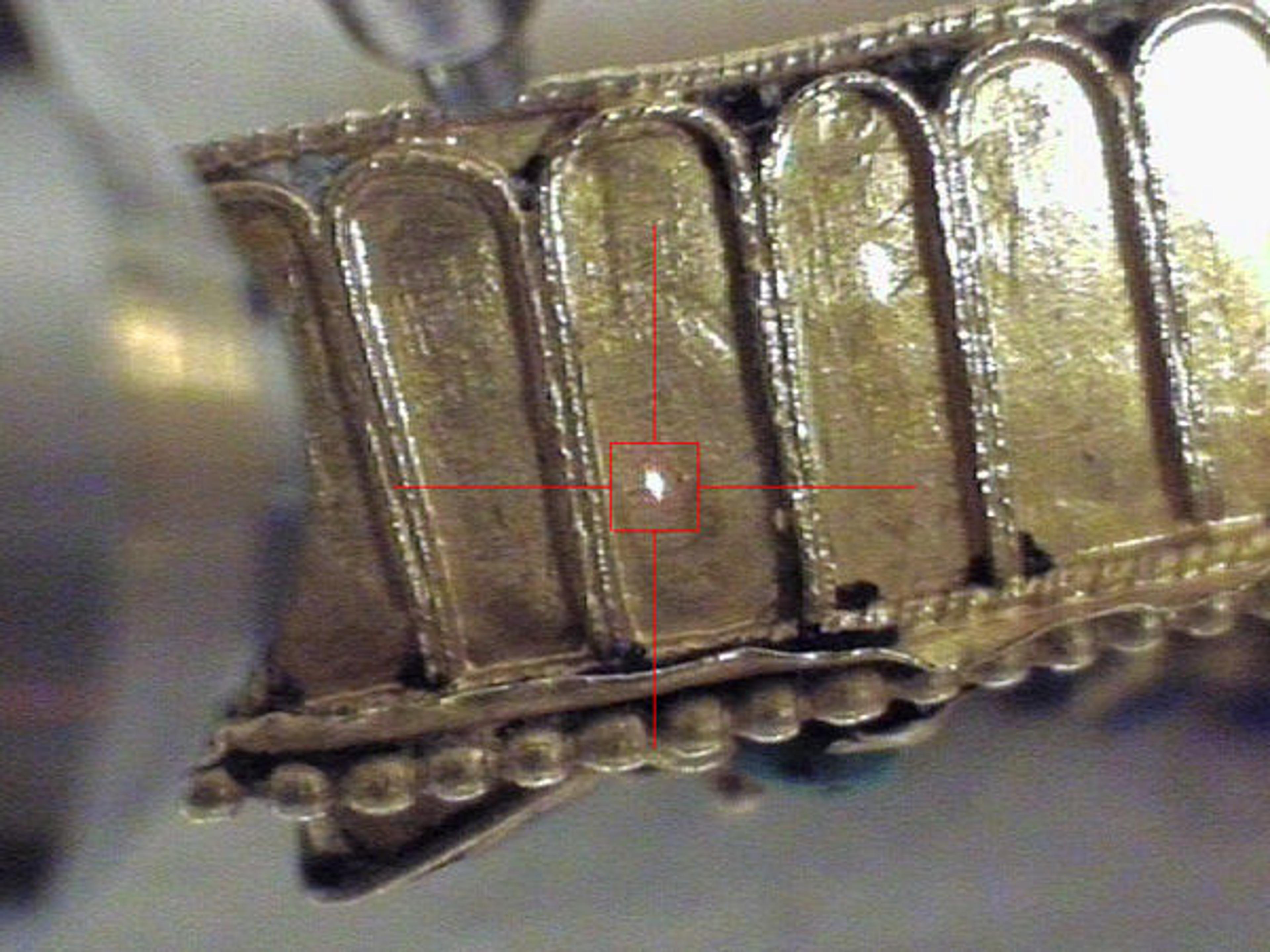

Detail view of 15.95.173 showing metal cylinder where stone is missing

The gemstones—rubies, emeralds, diamonds, garnets, and more—were usually held in place with a bezel, made by bending the edges of the metal cylinder over the top edge of the stone. Many also have a translucent shellac or wax material underneath in order to hold them securely in place. The opaque materials—turquoise, lapis, coral, and shell—are instead set into a thick layer of a red oil-resin material derived from plants and trees native to Nepal.

Detail view showing bezel setting (center red-orange stone) and opaque red-resin setting (adjacent turquoise and lapis stones). Dish for ritual offerings, 17th–19th century. Nepal. Gilt silver, rock crystal, emeralds, sapphires, coral, shell, lapis lazuli, and semiprecious stones; D: 8 1/2 in. (21.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1915 (15.95.168)

Many of the transparent stones have a tiny piece of silver foil beneath them, which catches the light and increases the reflectivity of the stone. Sometimes this reflective metal backing is given a dab of a pigmented glaze to enhance the color of a pale or colorless stone, as seen in the image below, where a small oval stone is missing at the center.

Detail view of 15.95.169 showing red lacquer on metal foil beneath a missing stone (center)

We also noted that the pearls usually had small holes in them. Since many of these decorative materials came from personal jewelry donated to a temple, it makes sense that the pearls had once been strung. Being able to identify and consider the reasons behind these choices provided a new insight into these objects and the people who made them.

Earring (detail), 17th–19th century. Nepal. Gilt silver, rubies, sapphires, pearls, lapis lazuli, coral, shell, and turquoise; 6 1/4 x 3 in. (15.9 x 7.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, John Stewart Kennedy Fund, 1915 (15.95.160)

X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was especially useful in identifying the metals as well as the stones on the objects. This technique beams X-rays at an object to produce the emission of secondary, or fluorescent, X-rays that are then measured by the instrument. The energies of these secondary rays help to determine which elements are present in the material. On an amulet box that I worked on, I concluded that the lid was made of gold with traces of copper and silver, while the bottom of the box was composed of silver with slight traces of copper. The solder used to attach the sides of the box to the bottom contains silver, copper, and zinc.

Detail view of 15.95.173a, b showing location of XRF analysis on the side of the box lid

All of these jeweled objects underwent conservation treatment to prepare them for exhibition. Most had a layer of dust and loose dirt on the surfaces as well as excess flux (a leftover material from the soldering process executed during the piece's construction) that obscured the details of the decoration. Conservators worked under the microscope with ethanol on cotton swabs to remove the dust, and a thin wooden stick to loosen the dirt and excess flux. While doing so, we were able to locate any unstable or detached decorative elements, and used a stable and reversible acrylic adhesive, Acryloid B72, to stabilize these components. Finally, the surfaces were gently vacuumed to remove the dislodged dirt and flux. After the treatment process was complete, the pieces appeared cleaner, the workmanship and fine materials could be viewed clearly, and the objects were deemed stable and therefore ready for handling and installation in the exhibition gallery.

Helping to research and preserve the Nepalese jewelry was an incredibly rewarding experience. Through this project the conservators helped achieve a greater understanding of how these objects were produced in the workshops of Nepal and Tibet, and the efforts to preserve them will allow people to enjoy their storied history in Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas as well as future displays.

View all blog articles related to Sacred Traditions of the Himalayas.

Follow the conversation: #SacredTraditions

Nina Pascucci

Nina Pascucci was formerly a college intern in the Department of Objects Conservation.