Audible Visuals: J. Kenneth Moore on the Met's Musical Instruments

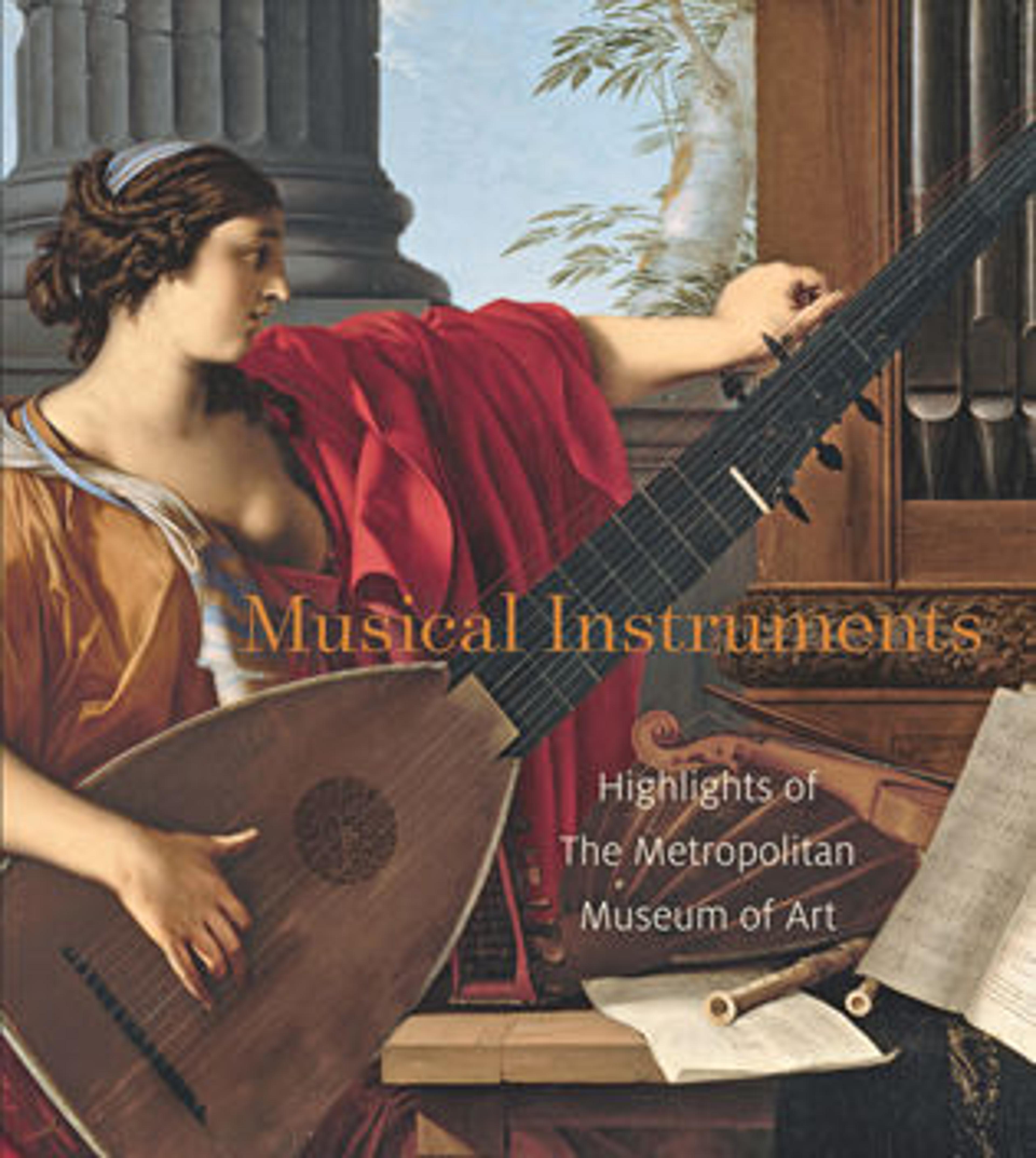

«Musical Instruments: Highlights of The Metropolitan Museum of Art presents over one hundred exemplary works from the Met's comprehensive collection of musical instruments, which spans thousands of years and cultures across the globe. I spoke with J. Kenneth Moore—Frederick P. Rose Curator in Charge of the Department of Musical Instruments and an author of this catalogue—about the instruments in the Met's collection, the connection between musical instruments and other works of art, and the stories behind these objects that are stunning both musically and visually.»

Left: Recently included in the 2015 New York Times Holiday Gift Ideas and Guide, Musical Instruments: Highlights of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, by J. Kenneth Moore, Jayson Kerr Dobney, and E. Bradley Strauchen-Scherer, features 261 color illustrations and is available at The Met Store and MetPublications.

Rachel High: Many of our visitors may be unaware that the Met has an extensive collection of musical instruments. How do you hope this book will draw attention to the objects?

J. Kenneth Moore: There are several art museums that have musical instrument collections, but we have the most comprehensive among art museums. The core of the collection came to the Museum, in 1889, through two gifts: the Joseph W. Drexel gift of about two hundred instruments from Europe and North Africa; and the Crosby Brown Collection, which included instruments from all over the world.

The Crosby Brown Collection was assembled by Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown, a true visionary ahead of her time who eventually grew the collection to almost four thousand instruments. She wanted to document music from all over the world and feared that non-Western musical traditions were going to disappear, a growing concern for many scholars of the time. Because of Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown, we have many instruments in the collection that no longer exist because the traditions didn't continue or the technology became outmoded.

This drum from the Crosby Brown Collection illustrates Mary Elizabeth Adams Brown's dedication to collecting musical art works as well as preserving non-Western music traditions. Attributed to Kodenji Hayashi (Japanese, 1831–1915). Ō-daiko (barrel drum), ca. 1873. Tohshima, Aichi Prefecture, Japan. Wood, metal, cloisonné, hide, silk, padding; H. of drum: 48.3 cm (19 in.), Diam. 55.88 cm (22 in.), H. of stand: 73.7 cm (29 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Crosby Brown Collection of Musical Instruments, 1889 (89.4.1236)

The Met's Asian, Egyptian, and Ancient Near East departments also collected instruments as artworks or archaeological documents. Musical instruments occupy this in-between space as both sound-producing objects and works of art. The ancient instruments that other departments have collected, in addition to the later pieces in the rest of the collection, puts the Metropolitan Museum in an incredible position to talk about the production, structure, technology, and role of music and instruments in society across cultures and through time. No other institution can do that, and that's why this book is so important.

In the book, the instruments are arranged chronologically. You don't have to be a specialist to appreciate the objects, the photos, or the objects' histories. The book also includes musical iconography (images of musical instruments) being used in various contexts.

The Met's collection of musical instruments spans from ancient times to the present. Left: Sistrum, ca. 2300–2000 B.C. Central Anatolia. Hattian. Copper alloy; 12.99 x 4.25 in. (32.99 x 10.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1955 (55.137.1). Center: Sistrum inscribed with the names of King Teti. Dynasty 6, reign of Teti (ca. 2323–2291 B.C.). Travertine (Egyptian alabaster), pigment, and resin; H. 26.5 cm (10 7/8 in.); W. 7 cm (2 3/4 in.); D. 2.7 cm (1 1/16 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926 (26.7.1450). Right: Sistrum with a dedication referring to a king, 332–330 B.C. Ptolemaic Dynasty. Silver; 29.6 x 6.9 x 4.2 cm (11 5/8 x 2 11/16 x 1 5/8 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Rogers Fund, 1958 (58.5a)

Rachel High: Music making is often depicted in other forms of art, and as you say, this book juxtaposes works in other mediums with the instruments themselves. How do these comparisons help us understand the instruments more fully? Is there anything you learned while making these pairings?

J. Kenneth Moore: The field of musical iconography actually began here at the Met with the first curator of the Department of Musical Instruments, Emmanuel Winternitz. One of the things you can learn from these depictions are performance practices. One great example in the book features the musicians' dressing room in a Japanese theater, where you see them preparing their instruments. It shows the ritual that one goes through before getting on stage, which, even today, is a relatable image.

Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760–1849). Dressing Room for Musicians at a Theater (Shitakubeya), early 19th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Japan. Polychrome woodblock print; ink and color on paper; H. 7 7/8 in. (20 cm), W. 21 7/8 in. (55.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929 (JP1857)

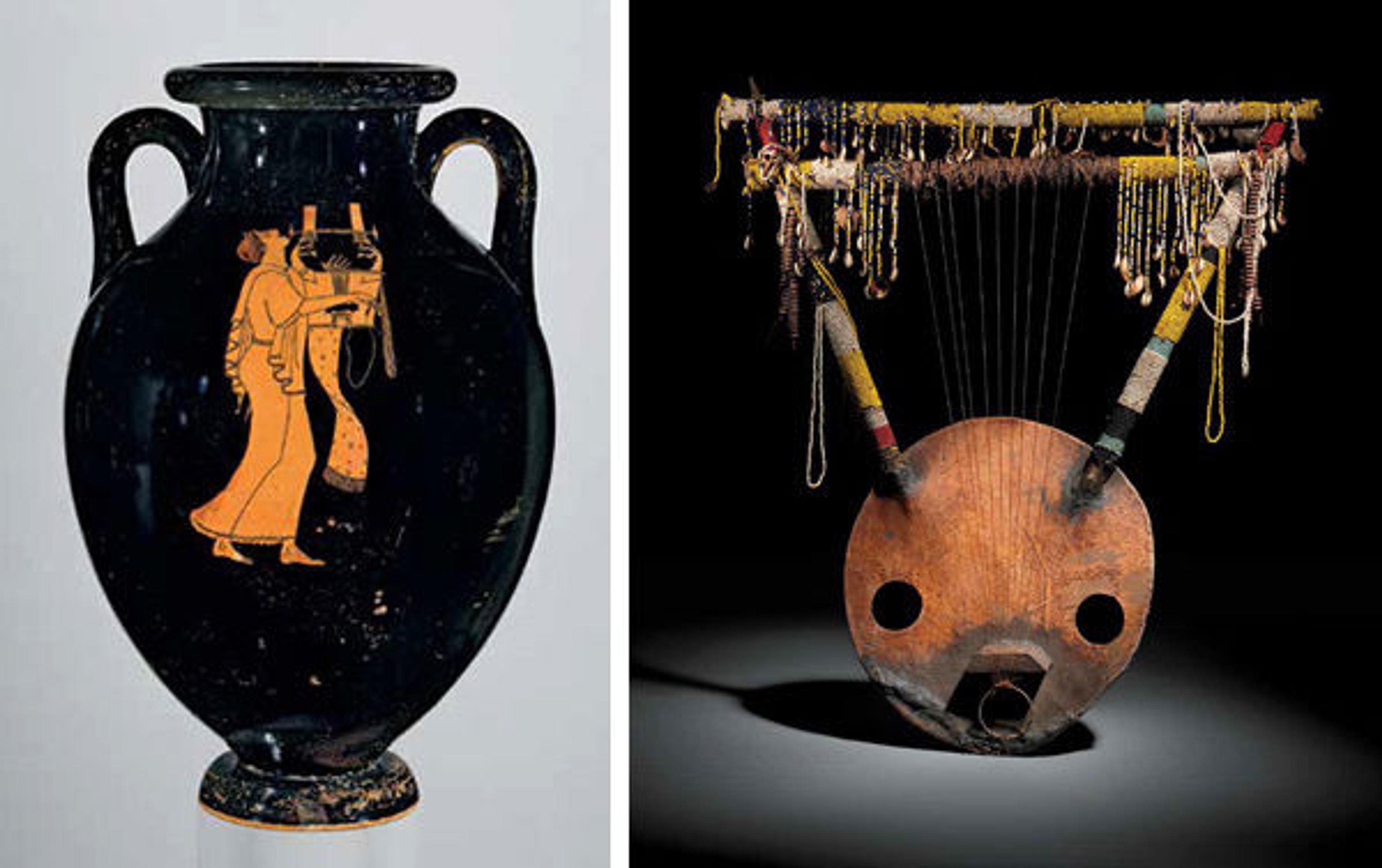

Another favorite one of mine is the Greek vase with the kithara (lyre) player, which complements the African lyre pictured next to it. Showing the same thing from two different cultures really sends a message of universality. The lyre is an ancient instrument found in many cultures. Both African and ancient Greek cultures used this object to accompany songs of heroic and epic deeds, so their function across time and place is the same.

Left: Attributed to the Berlin Painter. Terracotta amphora, ca. 490 B.C. Greek, Attic. Terracotta; red-figure; H. 16 5/16 in. (41.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Fletcher Fund, 1956 (56.171.38). Right: Kerar (lyre), early to mid-20th century. Ethiopian or Sudanese. Wood, beads, shells, fiber, metal, hide; H. 85.1 x L. 76.2 cm (33 1/2 x 30 in.). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Amati Gifts, 2008 (2008.54)

The figure on the vase has his head back. He's singing and you can actually see how he's plucking the instrument; you can almost hear it. On the other side of the vase is the judge; there have always been critics for any kind of art. The figure is plucking from the front of the instrument, stopping the strings with his fingers in the back, and a strap holds it in place. The African lyre is played in the same way. The juxtapositions to me are just magical.

Rachel High: This book covers over one hundred objects, but the collection of musical instruments is much larger than that. How did you decide which instruments to include?

J. Kenneth Moore: We wanted to show the breadth of the collection. Of course there are certain things we just couldn't leave out, like the Cristofori piano—the oldest and most important piano in the world—but there were many things that we couldn't include, and we hope people will come to the Museum to see the rest of the collection.

Rachel High: What instrument in the book has the best or most interesting story surrounding it?

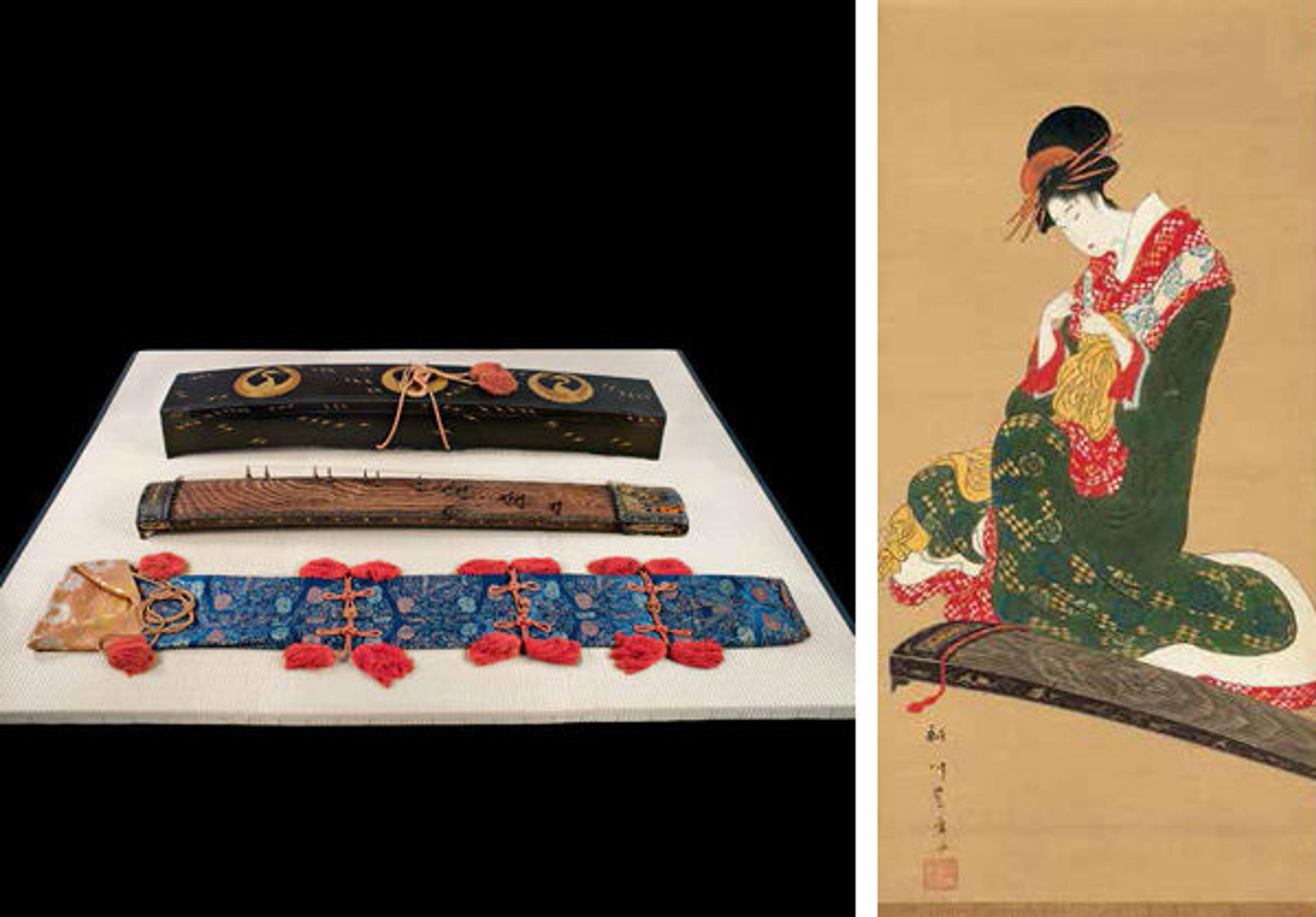

J. Kenneth Moore: My favorite is the koto, which was the featured work in my 82nd and Fifth episode. It is my favorite because it has to do with a rescue from a castle that was under attack. The son of the rescued man asked the person who saved his father what he would like as a reward, and this koto was made as the reward. We know that this koto was made for the Karasumaru family because the cranes decorating the case and the instrument is the emblem of that family. From that and other evidence, we can deduce that it was actually the son-in-law that rescued his father-in-law, and thus the brother-in-law gave this gift of thanks to his sister's husband.

I like the Utagawa Toyohiro work we placed with this object in the book because kotos are played with plectrums such as those seen on the hands of the woman in this painting, which reveals an intimate moment of the musician getting ready to perform.

Left: Koto, early 17th century. Japan. Metalwork by Goto Teijo, ninth-generation Gotō master, Japan (1603–1673); Workshop of Gotō Yūjō (Japanese, ca. 1440–1512, first-generation Gotō master). Various woods, ivory and tortoiseshell inlays, gold and silver inlays, metalwork. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Amati Gifts, 2007 (2007.194a–f). Right: Utagawa Toyohiro (Japanese, 1763–1828). Woman Putting on Finger Plectrums to Play the Koto (detail), early 19th century. Edo period (1615–1868). Japan. Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk; 31 5/16 x 10 1/4 in. (79.6 x 26 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Charles Stewart Smith Collection, Gift of Mrs. Charles Stewart Smith, Charles Stewart Smith Jr., and Howard Caswell Smith, in memory of Charles Stewart Smith, 1914 (14.76.43)

Related Links

The Met Store—Musical Instruments: Highlights of The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Learn more about the Department of Musical Instruments in the multimedia feature A Harmonious Ensemble: Musical Instruments at the Metropolitan Museum, 1884–2014, a comprehensive account of the history of the Department of Musical Instruments written by Rebecca Lindsey.

Rachel High

Rachel joined the Publications and Editorial Department in 2014 where she has previously held the roles of Publishing and Marketing Assistant and Assistant for Administration. She manages the MetPublications website, the Museum's text licensing program in all languages, and the @MetPubs Instagram account. In addition to her work marketing The Met's titles, Rachel also consults on Museum co-publications and the Costume Institute catalogues. She has been a speaker at the National Museum Publishing Seminar and is an organizing member of the International Association of Museum Publishers. She holds a B.A. in Art History from New York University and an M.A. in Art History from Hunter College. Her own research centers on the intersections of art and publishing.

Selected publications

“Something Else Press as Publisher.” Master’s thesis, Hunter College, City University of New York, 2020. CUNY Academic Works.