How Curators and Conservators Look at a Tapestry

«Understanding an art object requires close observation and an interdisciplinary course of investigation that integrates the work of curators and conservators, the arts and the sciences. This work, however, is often done behind a curtain (so to speak), and visitors rarely have the opportunity to gain insight into the process. On August 4, The Metropolitan Museum of Art will unveil the secret world of curators and conservators with its latest installation in Gallery 599, Examining Opulence: A Set of Renaissance Tapestry Cushions. This one-room exhibition will give visitors a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the fascinating and indispensable questions Museum curators and conservators pose as they investigate six luxurious, late Renaissance tapestry-woven cushion covers depicting scenes from the lives of biblical figureheads Abraham and Isaac.»

The second in a set of six tapestry-woven cushion covers depicting "The Expulsion of Hagar" from Scenes from the Lives of Abraham and Isaac, ca. 1600. Flemish. Wool, silk, silver-gilt thread (21 warps per inch, 9 per cm.); H. 19 3/4 x W. 20 inches (50.2 x 50.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of George Blumenthal, 1941 (41.100.57d)

Brand-new images of these tapestries, captured with microscopes and X-ray technologies by exhibition co-curator and conservator Cristina Balloffet Carr, will provide visitors with an intimate glimpse of the sumptuous materials, such as silk and gilded threads, used in the pieces. The rarely seen and complex backs of these tapestries—scarcely ever exposed to sunlight, and therefore more colorful than their fronts—will also be on view in double-sided cases, an arrangement that will allow visitors to get very close to and examine the extraordinarily detailed tapestries.

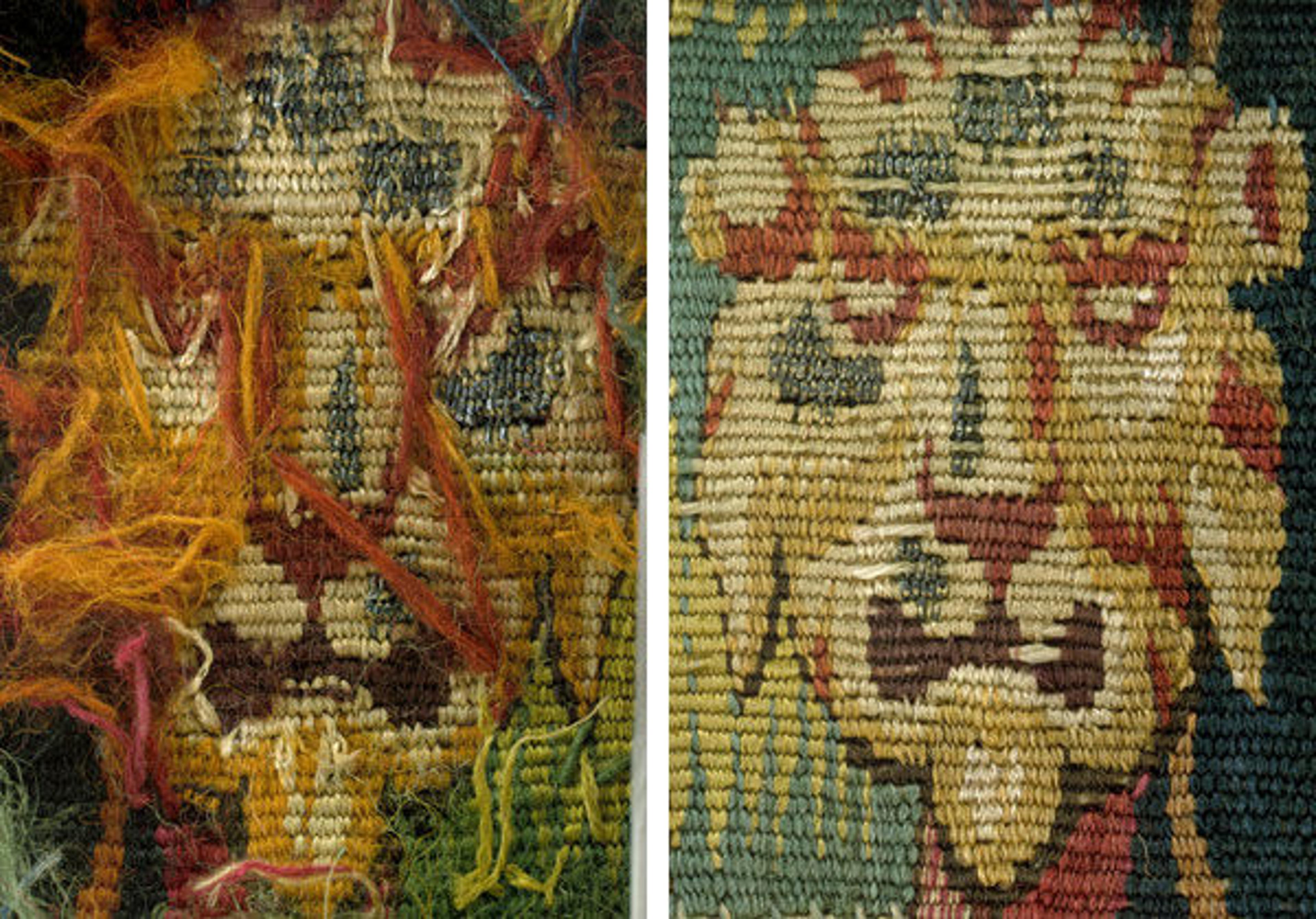

Left: Back detail of lion mask from "Abraham Entertaining the Angels" from Scenes from the Lives of Abraham and Isaac, ca. 1600. Flemish. Wool, silk, silver-gilt thread; 19 3/4 x W. 20 in. (50.2 x 50.8 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of George Blumenthal, 1941 (41.100.57e). Right: Front detail of lion mask from "Abraham Entertaining the Angels" from Scenes from the Lives of Abraham and Isaac. Photos by Cristina Balloffet Carr © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Curators and conservators strive to understand, preserve, and explain the significance of the works in a museum's collection; as such, their examinations are equally important responses to a work of art. Together, they reanimate an object's past, present, and future. Curators use a historical framework to contextualize a piece's function, subject matter, artistry, design, and production—exploring not only the life of an object, but also the lives of the people who made, bought, admired, or sold it. Conservators employ scientific methods to closely examine materials and techniques for the historical information contained within a work of art itself. From X-rays to high-powered microscopes, increasingly nimble digital technology allows conservators to determine how and when an object was made. Conservators are also responsible for monitoring the physical well-being, care, display, and preservation of a collection.

As part of her research, Carr captured astonishing images of tapestry threads and weaving techniques through the lens of a microscope. Her close examination yielded, among other fascinating discoveries, an image that shows traces of gilding on now gray-colored metal strips wrapped around a yellow silk core. When new, these metal-wrapped threads would have shone a brilliant gold.

Detail of threads from "Abraham Entertaining the Angels" from Scenes from the Lives of Abraham and Isaac. Photo by Cristina Balloffet Carr © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Sarah Mallory, research assistant in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, also studied the cushions, turning her attention to exploring the objects' provenance, design sources, and artistry. Among other fascinating insights, they found an image of the cushions being used as decorative pillows in the (now-demolished) Park Avenue home of George and Florence Blumenthal. George Blumenthal—a notable collector and seventh president of the Metropolitan Museum—and his wife, Florence, purchased these cushions with the intention of giving them to the Museum. Though Florence died in 1930, George followed through on their promise and the cushions became part of the Met's collection in 1941.

View of the Scenes from the Lives of Abraham and Isaac tapestry-woven cushion covers being used as throw pillows in the Blumenthal household. From the album The Home of George and Florence Blumenthal, Fifty East Seventieth Street, New York, 192-?. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Watson Library (106.1 B622 F)

As a result of research conducted by both curators and conservators, we know that these finely woven cushions were, and remain, an embodiment of Renaissance opulence. They contain an abundance of costly materials, such as gilt thread and dyed silks, which could have only been affordable to wealthier individuals in late Renaissance Europe. The cushions' backs reveal the rich range of hues in the threads—this variety of color being another sign of their costliness. The well-preserved state of the pieces indicates they were not intended to be used as furniture cushions or throw pillows, but rather were stowed away for use as personal devotional objects, which only wealthier individuals could have acquired.

Related Links

Examining Opulence: A Set of Renaissance Tapestry Cushions, on view August 4, 2014–January 18, 2015

Now at the Met—The Dyes Have It: Exploring Color and Tapestries

Sarah Mallory

Sarah Mallory is a research assistant working with Associate Curator Elizabeth Cleland in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts.

Cristina Carr

Cristina Carr is a conservator in the Department of Textile Conservation.

Elizabeth Cleland

Elizabeth Cleland is an associate curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts.